After my earlier five-part series I managed to go a month without writing anything new about coronavirus. That ends today. But since this blog is about second-order effects (and because part of me still needs a break from the topic) I’m not writing about coronavirus in a conventional way. Instead, I’m revisiting a topic I first covered a year and a half ago and looking at impact from COVID-19.

That topic: the changed market for illegal substances (rhino horn and cocaine for now) and how they flow around the world.

In the midst of all the global health concerns you might wonder why I would return to the topic of rhino horn and cocaine when I could also write about so many other issues. I returned to this topic because by looking at the systems behind these illegal trades we can understand other issues relevant for COVID-19.

Rhinoceros horn (baseline)

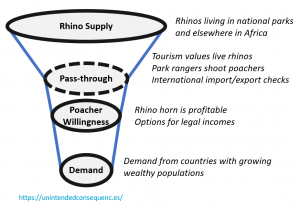

First let’s look at the system that produced the trade in rhino horn pre-coronavirus.

I drew this system diagram like a funnel to represent the paths and blockages of going from rhino to customer.

The price of rhino horn (around US$60K/kilo) is pretty close to the retail price of cocaine. Since entire horns are often delivered to buyers and then processed I compared the cocaine wholesale market (per kilo) rather than retail (priced per gram and usually at double the wholesale price).

Note that the baseline is based on an existing historical or traditional demand for rhino horn as a status-granting traditional medicine. It’s history, tradition, status and placebo effects at work here rather than medical addiction or studied effectiveness against an illness. Recent increased wealth in China and Vietnam increased demand rather than creating the demand.

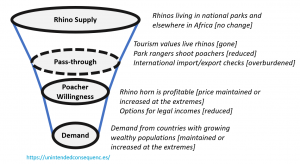

Rhinoceros horn new normal (during coronavirus)

In the coronavirus pandemic a few things change about the above funnel.

Pass-through. With no tourists the business model for live rhinos is gone. Without as much revenue to pay park rangers, there are fewer patrols of the large parts of Africa in which rhinos live. More of the rhino population is at-risk.

Poacher willingness. With fewer risks to hunt rhinos and fewer other sources of income, the risk-reward calculation changes. People who might have sought other ways to make money instead hunt rhinos. Get while the getting’s good.

Demand. Interestingly, demand remains. First, the wealthy who demanded rhino horn in the first place are still quite wealthy. I’ll make the assumption that people who dropped US$60K per kilo for a rhino horn of one to three kilos in weight will still have plenty of disposable income.

The second reason is that rhino horn is now being marketed as a treatment for coronavirus.

A report from the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine lists a traditional medicine Angong Niuhuang Wan, which includes rhino horn, as a cure for some effects of coronavirus. The report is here. Search for Angong Niuhuang Wan (安宫牛黄丸) in the document. This, and other casual reports about the use of rhino horn as a coronavirus treatment make me think that rhinos are going to have a tougher time for the next year.

As I wrote in Anything at Scale:

“Unlike the demand for other illegal drugs such as heroin (from opium poppies) and cocaine (from coca leaves), rhino horn is an animal product and not renewable in the ways it is illegally collected today…. Two black markets exist for rhino horn in China and Vietnam. One is for medicinal purposes and the other for luxury products carved from the horn…. And the number of rhinos poached grows with demand from wealthy in China and Vietnam: from 60 rhinos in 2006 to 1,342 in 2015….”

China also banned rhino horn as a traditional Chinese medicine ingredient starting in 1993, but to less of an effect.

But ironically, just one month after I posted the Anything at Scale article (September 2018), the ban was reversed. According to the SCMP:

“[R]hino horn for medical treatments can be prescribed by doctors certified by the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, according to the announcement.”

Further to this, as reported in October 2018:

“Rhino horns… used in medical research or in healing can only be obtained from farmed rhinos…, not including those raised in zoos. Powdered forms of rhino horn… can only be used in qualified hospitals by qualified doctors recognized by the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine.”

Restrictions seem to have increased again in December 2018:

“[T]he following ‘three strict bans’ will continue to be enforced: strictly ban the importing and exporting of rhinos, tigers and their byproducts; strictly ban the sales, purchasing, transporting, carrying and mailing of rhinos, tigers and their byproducts; and strictly ban the use of rhino horns and tiger bones in medicine.”

However, seeing the above medicine marketed on a government agency website makes me think that there are still loose ends when it comes to rhino horn. Is rhino horn marketed as a coronavirus cure because it’s possible to source the horn more easily today?

Second-order effect of coronavirus: more dead rhinos.

Cocaine (older baseline)

The cocaine market that developed in the past 50 years relies on coca supply based in Latin America and demand centered in the US. Coca leaves are processed and the finished product was often illicitly delivered by boat to ports in the US for distribution. The cocaine demand that grew in the US in the 1980s was, like the rhino horn example above, in part fueled by rising US disposable income.

Cocaine (newer baseline – from sea to land)

This obviously varies depending on location, but $30K to $80K per kilo wholesale is pretty common around the world. I’m sourcing info from a few places for this.

As described in Accidental Superpower, by Peter Zeihan, Mexican drug cartels formed after tougher coast guard monitoring made shipping cocaine by boat to Miami impossible. When it was easy to land a boat in southern Florida there was no reason to transport cocaine by land — a more dangerous and costly pathway which added around $10K in costs per kilo. But, as Zeihan writes, moving from sea to land:

“adds more than simply cost. It also ensures that the shippers become intimately involved in every aspect of their transport routes. And should shippers using two different routes find themselves operating at the same bottleneck – say a mountain valley where their routes merge, or an international border crossing – competition erupts.”

Result: Mexican drug cartels fight over transport routes and market access.

Cocaine new normal (during coronavirus)

Illegal border crossings on the southwest US-Mexico border for the first few months of 2020 are down, but not what I’d call by definitive amount. Over the last few years we saw a decline after Trump was elected (fewer attempts) but then a spike in 2019 which might because of higher patrolling.

During the height of coronavirus, there may be fewer people available to transport product across the Mexico-US border. But, those fewer people may also have more reasons to seek income. Plus, there may be fewer people to patrol the border. Overall, it’s not yet clear whether coronavirus impacts the ability to deliver cocaine, but I won’t be surprised if the cartels start to experiment with other means of transport, including more packages in cross-border trucks and other shipments. Distributors even ship cocaine by mail in smaller quantities.

Second-order effect of coronavirus: a more robust distribution network that survives long-term?

Consider

- What other illegal drug sourcing will change because of COVID-19? Will the changes make the drug’s logistics more dangerous, change pricing, or supply?

- What are the health effects of changes in supply and ability to pay?

- What cures do we see because they become possible to deliver effectively, rather than because they are useful?

If you liked this post you might also like Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.