Long-time readers of this blog know that I wrote about how disease spreads several times well before the recent coronavirus news. And then I wrote three posts on that. I’m hardly alone in my interest on this topic.

But apart from what we’re going through now, infectious diseases generally don’t get as much attention as I think they deserve. In terms of unintended consequences, I’m interested in the impact of disease on human decision making and where things went wrong, or well, in the past. As for the potential impact of COVID-19 in the near-term, some minds are changing in the midst of political, business, social, and educational impact.

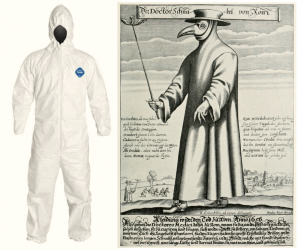

And then there is the look back in history. When I recently learned the story of a European plague year’s impact on Dutch “tulipmania,” the modern and historical protective images intrigued me as well.

Two camps

Many people have commented that on the topic of COVID-19, two sides are battling for mindshare. There are the “doomsayers” who stress the dangers of exponential growth and a purpose to panicking. Then there is the “don’t overreact” side who stress that things will turn out fine and that the panic may actually cause other problems.

Both sides have their reasoning. In this situation I’m on the “doomsayer” side for increasing the response that would slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. I do also know that there may be those who also suffer because of the responses themselves.

Here are a few examples from the “don’t overreact” side.

This tweet by Peter Diamandis, who calls himself an “exponential entrepreneur,” is curiously not exponential in thinking. The three diseases listed, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes, are not communicable. They do not grow with exponential processes. They cannot spread quickly around the world.

Like the thought experiment I wrote about in Autonomous Vehicles and Scaling Risk, even if you wanted to, increasing the number of people who die from cardiovascular diseases isn’t possible without a large policy change, like ceasing treatments. Living in an system which enables the fast spread of communicable disease (international travel, proximity to others who are sick, practices like shaking hands and large public gatherings) is different.

This article by Cass Sunstein (of “nudge theory”) opens with this contradictory quote. “At this stage, no one can specify the magnitude of the threat from the coronavirus. But one thing is clear: A lot of people are more scared than they have any reason to be.”

But the most extreme (because of his following and position) unfortunately was this tweet from Donald Trump:

“So last year 37,000 Americans died from the common Flu. It averages between 27,000 and 70,000 per year. Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of CoronaVirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that!”

This could be a very costly tweet, both in terms of public behavior and the election. Instead, can “overreacting” be a logical thing to do if it means more people wash their hands and cancel trips and large events? Why encourage unpreparedness if fast viral growth could quickly overwhelm medical facilities?

Here are some unexpected early outcomes of the coronavirus.

Products demanded at a distance

As fewer people and goods move around the world, prices change.

For example, we saw a quick price decrease in seafood. From catch to consumer, seafood’s freshness demands quick delivery. That’s why cancelled international flights means reduced demand.

- The price of lobsters has fallen. Without being able to fly fresh lobsters to China, demand is at “5% of normal volumes…”

- This article on demand for geoduck: “At last week’s auction, the price per pound came out to $5.78… which is well below the $16.05 per pound average bid in 2017 before the trade war.”

- And on young eels (called elvers): “Maine elver fishermen were paid an average of $2,093 per pound for their catch in 2019… [A]n elver buyer and exporter who also is looking to establish eel aquaculture operations in the U.S. and Canada, said that concerns about coronavirus’ effect on the eel market have sent prices tumbling. As of Wednesday, he said, the going price for elvers being caught in the Caribbean is roughly $800 per pound, half of what it was on opening day of Maine’s 2019 elver season.”

A second-order effect of restrictions on international shipments impacts demand for specific foods. Unlike the growth in prices driven by a wealthier Chinese consumer, as I wrote in Anything at Scale, I expect price declines in other products that depend on an international market (not necessarily just China) for their sales.

Education

China closed its schools indefinitely and classes are online until COVID-19 is under control. Japan also closed its schools (though its students continue to congregate socially). Italy sent overseas exchange students home from locations in the north, a region now under quarantine. In Italy, similar to scenes in Wuhan in January, quarantining a region can lead to chaos, especially if the plans leak to the press before the official announcement.

That brings us to the US. More schools have moved to run classes remotely. The University of Washington was the first to close its campus after a coronavirus outbreak in Seattle. Stanford recently moved its classes online for the rest of its quarter. And USC, where I teach, will keep the campus open but require remote teaching from March 11 – 13, right before spring break. That experiment, which I am all for, will provide time to test remote teaching capabilities and adjust if classes continue remotely after spring break (I won’t be surprised if they do).

Seems likely to me that once a campus closes it will most likely stay closed for the remaining weeks in the semester. Who wants to be the cause of a local outbreak?

I believe that if online education replaces in-person classes for long, we’ll see more arguments against the hike in US college tuition prices, even though only a small percent of US university tuition goes toward paying for the education itself. As I wrote in College Admissions Scandal:

“My rough calculation of what the needed four-year college credits would cost if students just directly paid adjunct professors: around $10,000. Make that $20,000 to $30,000 for only full time professors. Bear in mind that a four-year degree often costs around $250,000 today.”

If classes continue remotely and if campuses close for long, will colleges be under pressure to reduce tuition, even temporarily? After all, students will lose many benefits of going to a physical university.

Planned gatherings

The response outside China is mixed.

Austin canceled SXSW (400k attendees). The Natural Products Expo West postponed its large convention (100k attendees). But Los Angeles did not cancel its marathon (25k participants).

On the political side, two people were infected with coronavirus at the AIPAC conference, and there was at least one infected attendee of the CPAC conference. The large political rallies for Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, and Donald Trump are starting to look irresponsible, yet in an election year, it’s understandable why organizers want the gatherings to proceed. The large gatherings during an election year is the US version of the large movements of people during Lunar New Year at the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. And ironically, all three presidential candidates are in the prime age group for COVID-19 fatalities.

So far, government officials in France and Iran, among other locations have tested positive for or died because of COVID-19.

Then there was this precautionary response from Sen. Ted Cruz in the US:

“I was informed that 10 days ago at CPAC I briefly interacted with an individual who is currently symptomatic and has tested positive for COVID-19… [T]he medical authorities explicitly advised me that, given the above criteria, the people have have interacted with me in the 10 days since CPAC should not be concerned about potential transmission. Nevertheless, out of an abundance of caution, and because of how frequently I interact with my constituents as a part of my job and to give everyone peace of mind, I have decided to remain at my home in Texas this week, until a full 14 days have passed since the CPAC interaction.”

Large gatherings are opportunities for “super-spreaders” to infect many people unknowingly. A super-spreader in Italy did not know he had coronavirus (and actually went to the hospital three times before finding out). In the meantime he spread the disease to many others.

Will organizers who do not cancel or postpone large conferences be held accountable should their participants fall ill and die?

Wealth transfer

The coronavirus case fatality rate is different from other communicable illnesses, like what I’ll simply call the seasonal flu in that it hits the older population much harder than the young population. Case fatality rates are estimated at 0.2% below the age of 40 and rising to 8% for 70-79 year-olds and over 14% for those over 80.

While the fatality rates of plagues in Europe centuries ago were much higher than COVID-19, I found an echo from the 1636 – 1637 rapid increase in the price of tulip bulbs in Holland. (Those years were plague years.) If you don’t know the story, certain types of tulip bulbs grew in value to the point of being worth as much as a house.

From Tulipmania, by Anne Goldgar (p 257-8):

“Yet with such major and protracted mortality there will have been many repercussions. One of these was certainly financial. Death meant inheritance, and with so many people dying, estates, which were often divided up among many members of families, would have been quickly providing unexpected capital to potential buyers of tulips. One example is Geertruyt Schoudt, who was persuaded… to buy a pound of Switsers [a type of tulip] precisely because she was expecting to receive part of the estate of her late brother-in-law…”

“Large-scale mortality from plague caused social upheaval; the redistribution of wealth did the same.”

Localized ecosystems

Throughout the international reaction to COVID-19 I can’t help but think of the history of a shoe factory near where I grew up.

The factory had been a major employer in the area and at one time produced a few percent of all shoes bought in the US. They were vertically integrated, as many factories used to be, producing their own rubber for soles (from used tires), tanning animal hides, and more.

This integrated factory, like many others, didn’t survive the move to globalized supply chains. But I wonder if factories in the future will be designed with a degree of self-sufficiency in mind.

Consider

- Since the novel coronavirus is such a severe disease, with fatalities much higher than a typical flu, if the entire medical system is overwhelmed, then people who need treatment for other issues won’t receive it.

- Don’t compare exponentially growing diseases with relatively stable causes of death (like car accidents).

- What impact may come from the unexpected early deaths of an older demographic?

- Will people found to have spread COVID-19, or to have created environments where it spread (like large public gatherings), later be held responsible?

- What will the future balance of global and local look like?

This is the unexpected fourth article in a series on coronavirus. You might also like to read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 5.