Apart from the obvious impact on lost life, the shared global presence of COVID-19 captures everyone’s imagination when it comes to other consequences. COVID-19 is impacting just about everyone on earth in some way.

In this post I consider some of the impacts related to commerce. (If you’re new, here’s the first article I wrote about coronavirus).

Confused supply

People in the US previously never adopted the use of face masks when they fell sick. Apart from the lack of previous high-profile infectious respiratory diseases, there was a long debate (some say bait-and-switch) over whether masks were really necessary. The debate, where the World Health Organization also weighed in, included recommendations against using masks.

Regardless, the US and many other countries quickly discovered that they had depleted their mask stockpiles years ago and that their manufacturing capabilities could no longer produce enough of them quickly enough.

But certainly existing US manufacturers would run three shifts and bring more equipment on board to ramp up production as fast as possible, right?

Not necessarily.

Here’s an explanation from Michael Bowen, an owner of Prestige Ameritech, the largest US supplier of face masks, as interviewed by Mary Louise Kelly from NPR.

KELLY: This is a very basic question, but why can’t you ramp up really quickly, really fast? This is a question of specialized equipment?

BOWEN: Yeah, and training. It takes a long time to build the machines, and this is a temporary situation. So for our company, ramping up past a certain point becomes a suicide mission. You know, we did this 10 years ago during H1N1, and we hired a lot of people and ramped up. And then we nearly went bankrupt afterward. We laid off 150 people and nearly went out of business. You know, it’s not like flipping on a switch. It’s building machines. It’s hiring people. It’s training people. That’s the issue.

KELLY: Stay with that experience from 2009 with H1N1. You ramped up. You were left with – what? – a huge surplus of masks that you couldn’t sell?

BOWEN: Well, what happened is we rose to the occasion. Hospitals were calling. We bought a bigger factory. We built machines. We hired an extra 150 people. And then when it ended, the people that we helped went back to the foreign-made masks. So we ended up having to lay off all of those people, and it was a very brutal situation.

Confused demand

When a customer can’t travel to the product, you can deliver the product to the customer. But that doesn’t work when the product is tourism.

Let’s look at rental cars for an extreme example of unintended consequences.

The growth in the rideshare businesses (Uber and Lyft in the US) has already hurt the rental car business. But the growth in rideshare impacted some destinations more than others. Urban locations with expensive parking and bad traffic tended to adopt rideshare more. (I’m speaking generally and not counting local struggles over rideshare legality. Rideshare companies have certainly damaged local businesses as they expanded, which I wrote about in Anything at Scale.)

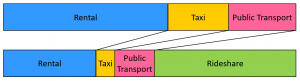

In many cities, pre-rideshare transport options were rental cars, taxis, and public transport. A representative pre-rideshare and post-rideshare breakdown of an urban market’s transport industry might look like this.

Post-rideshare, the rental, taxi, and public transport options shrunk as a percentage of the market. Overall transport might have increased, but the percentage of each form of transport changed.

What happens when coronavirus stops tourism? Let’s look at an extreme example.

In Hawaii, there are “thousands of rental cars parked in a Hawaiian sugar cane field after the coronavirus pandemic halted tourism.”

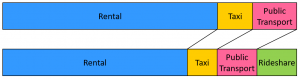

We’re reading about the car rental effect from a place like Hawaii because car rental agencies there were more exposed to traveler risk than other locations. I don’t have hard numbers for this yet, so I’m making estimates on how this unintended consequence unfolded. A representative pre-rideshare and post-rideshare breakdown of Hawaii’s transport industry might look like this.

Rental car agencies in Hawaii originally suffered less from rideshare businesses since many Hawaiian locations are fun to explore throughout the day. In Hawaii, in many situations, you don’t just need a short drive by Uber to a destination where you then pick up another car to return. Since Hawaii felt less of an impact from rideshare, its rental car business stayed large and was more exposed to the loss in travelers.

Because those rental car agencies earlier did well while other locations suffered from rideshare, they now feel the lack of tourists more severely. Result: sugar cane fields of rental cars.

Confused logistics

Food waste is common, certainly in developed markets. Waste and attempts to cut waste (if it makes sense) may look like a big deal, but in relation to the overall food market, not be such a bid deal after all.

When I heard about coronavirus-related milk, egg, and farm produce dumping, my first question was on how different the amount of waste was from the norm. I don’t have a full picture yet, but from the articles I’ve seen it doesn’t look like the reports of waste are as extreme as they sound.

The reason is that waste — famously in US dairy — is the norm.

In “Wasted Food, Wasted Energy: The Embedded Energy in Food Waste in the United States,” we learn that in the “North American supply chain, 31.4% of all eggs produced end up as waste” and in the “North America supply chain wastage was found to be around 32% and USA retailers were found to waste around 9% of all dairy products.” The paper is from 2010 and much of the data is from the 1990s, so I write assuming that the milk and egg waste problem has not dramatically changed since then. Another data point from another source is that 26% of milk and dairy (split between consumer and retailer) was wasted in the US in 2016.

I earlier wrote about the political power of the dairy industry, and the glut in milk which resulted in massive milk waste and cheese storage across the US. Government support for the price of milk led to overproduction, “government cheese,” and pushing producers to include more cheese in their products.

So it’s odd to hear about coronavirus-related milk waste because farmers can’t get their milk to market. Wasted milk has been part of the dairy industry for a long time.

But does an coronavirus market delay impact all milk in the same way?

There are several ways to preserve milk for its trip to the customer. There is pasteurization, refrigeration, processing into other longer-lasting foods (yogurt, cheese) and also ultra-high temperature processing. Ultra-high temperature processing (UHT) allows milk to stay in a non-refrigerated container for up to six to nine months.

UHT milk is sold widely in European markets, but the technique never took over the market in the US, perhaps because of flavor changes.

The UHT process is however used for much of the organic milk in the US, even if the product is sold from the refrigerated aisle. Since there is a smaller market for organic milk and it is not produced everywhere, its supply chains tend to be longer. This led to the quiet adoption of UHT for organic milk, which has lower production and a smaller number of customers than conventional milk.

So perhaps we’ll find that organic milk is even less at risk of slower supply chains, compared to conventional milk. This difference will not be seen by the consumer, however.

Confused format

As we’ve learned about toilet paper, there can be plenty of product (no shortage) but just in a format (size or style) that doesn’t work when demand suddenly shifts from mixed commercial and home to almost entirely at home. There can be plenty of product (true use for toilet paper hasn’t increased) but people using it at home instead of in their workplace shifts the location (and format) of demand.

One small story that caught my eye was about a watermill in England that now has more customers for its stone-ground flour than it can handle (“Boom in home baking helps struggling watermill“). This mill suddenly has extra customers because commercial flour production is built around larger bags of flour sized for commercial bakers. Secondarily, there has been a surge in home baking.

To boost production, the factory (like the face mask mills) could add workers and equipment. But would that make sense?

Confused production

Again from the earlier NPR interview with the mask producer:

KELLY: I mean, make the case for me why the government and private business – why shouldn’t they go with the cheapest option?

BOWEN: Because in a pandemic, the government of every country is going to take care of their own people. If there’s not going to be a pandemic, it’s no big deal. But if you think there’s going to be a pandemic – which experts do – and that borders are going to close and there’s going to be infrastructure disruption, it’s safer to make masks in the United States.

How do you choose, in advance, what products and producers are part of that national interest?

Consider

- What do small non-self sufficient countries do in extreme times?

- Who wins and loses in times of crisis is sometimes planned in advance and sometimes happenstance.

- Apart from medical-grade masks, another US-based company released plans to produce up to 100 million cloth masks a week.

- Related to waste and changes in demand (for food, above), news from when I was finishing this includes that oil futures have gone negative. There’s a shortage of places to store the oil.

If you liked this post you might also like Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6.