I’ve already written two earlier posts (one and two) on second-order effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19). Let’s now take the coronavirus situation to think through unintended consequences in a different way. For this post, I’m focusing on disinformation as related to the spread of disease.

What are some of the tactics used to spread disinformation, what are some cases of disease-related disinformation in history, and how will things possibly change over time and place?

What are some of the second-order effects coming from the different ways we communicate today, information’s ability to spread widely and cheaply, and even the surprising longevity of digital information?

And unlike many of the other posts on this site, is there more benefit from centralized best practices than in keeping different healthcare practices?

As I quoted in an earlier post (Prester John and the Long History of Disinformation):

“While misinformation may come from honest mistakes, disinformation is intentional. Its purpose is to mislead and harm. Historically, we see this in propaganda issued by a government organization to a rival power or the media. I like the definition from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Disinformation is “false information with the intention to deceive public opinion.’”

History of related action

HIV / AIDS. Operation Infektion was the most famous example of state-led disinformation about AIDS.

Also from Prester John and the Long History of Disinformation:

“In 1992, 15 percent of randomly selected Americans considered definitely or probably true the statement ‘the AIDS virus was created deliberately in a government laboratory.’ African Americans were particularly prone to subscribe to the AIDS conspiracy theory. A 1997 survey found that 29 percent of African Americans considered the statement ‘AIDS was deliberately created in a laboratory to infect black people’ true or possibly true. And a 2005 study by the RAND Corporation and Oregon State University revealed that nearly 50 percent of African Americans thought AIDS was man-made, with over a quarter considering AIDS the product of a government lab.” — Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign (p 19)

The effects of this disinformation campaign the majority of impact on people in the US and elsewhere after the USSR had already dissolved. Ironically, this disinformation campaign may have affected non-Americans more than Americans by convincing them that US-produced condoms and treatments were responsible for the spread of HIV.

Ebola. Ebola was made worse partly through the low trust in local systems.

From a report on Ebola in Western Africa:

“[L]ocal state authorities are often negatively perceived among the population and many locals do not consider them as being trustworthy sources. Some conspiracy theories actually accuse local governments to have set things in motions to get access to aid money or gain votes in the elections…. There are some noteworthy examples where various individuals took matters in their own hands to inform their fellow citizens via YouTube. For instance, some Liberians posted videos on proper hand washing on YouTube, and a Liberian rapper named Shadow made music videos called “Ebola in Town,” which cautions against touching and kissing and links Ebola to eating bush meat.”

False information is hard to wipe out online, even from legitimate sources. As the BBC reported in 1999 (years before the more recent Ebola scares): “A plant has been found to halt the deadly Ebola virus in its tracks in laboratory tests…”

Kola nut (the plant mentioned) is not a cure for Ebola. But that claim was repeated during the 2014 Ebola scare. For that matter, the original BBC article is still online. Another mainstream article with the same claim is also still online.

Even more ironic, another BBC article (this time from 2014) reverses the earlier claim. “A message declaring that a plant can “cure” Ebola is being widely shared via mobile phone in West Africa – but the claim is not true, and may be offering false hope to those living amidst the outbreak.”

But again, the original BBC article remains online. (Interestingly, this was what I found in the earlier disinformation post as well, but that time as related to reports about looters in a Baghdad museum.)

Vaccines for measles and other diseases. Vaccines (and just about everything) do have risks. This set of disinformation and misinformation has grown in recent years and has been connected to “antivaxer” groups. In terms of mainstream public attitudes, we even have this 2014 antivax tweet from Trump (though he later encouraged people to get vaccinated):

Healthy young child goes to doctor, gets pumped with massive shot of many vaccines, doesn't feel good and changes – AUTISM. Many such cases!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 28, 2014

We could expect that the decades-long mainstream activity of vaccinating children for health benefit would eventually find a growing group of people who believe that vaccines are harmful. Edge cases, coincidental timing of illnesses, and lack of awareness of what is in the vaccines can all contribute to “antivaxer” beliefs, especially when paired with an increase in autism and vaccine protocols that are based on public policy.

But antivaxer beliefs have been growing.

This is from an open letter from the American Medical Association to CEOs of several large tech companies.

“At a time when vaccine-preventable diseases, particularly measles, are reemerging in the United States and threatening communities and public health, physicians across the country are troubled by reports of anti-vaccine related messages and advertisements targeting parents searching for vaccine information on your platforms…. With public health on the line and with social media serving as a leading source of information for the American people, we urge you to do your part to ensure that users have access to scientifically valid information on vaccinations, so they can make informed decisions about their families’ health….

“As evident from the measles outbreaks currently impacting communities in several states, when people decide not to be immunized as a matter of personal preference or misinformation, they put themselves and others at risk of disease. That is why it is extremely important that people who are searching for information about vaccination have access to accurate, evidence-based information grounded in science.”

Fighting disease-related disinformation is difficult.

Some of that difficultly stems from the way people receive information on diseases and methods of prevention.

Some of that difficultly stems from the development of a top-down public policy approach that aims to serve most of the population (and often the high-risks parts of the population).

The antivaxer movement is an interesting twist on the other examples in that this one also targets people in parts of the world where there should be higher trust in local systems. It’s a reminder that countries small and big have diversity of beliefs. (Reasons behind the antivaxer community’s growth will have to wait for another article.)

This decline in vaccination rates is also seen with preventable diseases such as HPV. The quick declines in HPV vaccination rates in Denmark (best chart is page 12 in the linked presentation) are interesting in that Denmark is a country in the EU with high rates of systems trust. Even here, attention to the exceptions can tell many stories.

Another example of the quick breakdown in trust is from the Philippines. Reports of risks from a dengue fever vaccine led to a dramatic fall in public confidence (see charts on linked article).

Same for a call from Boris Johnson for maintaining the herd immunity created in the UK by mainstream measles vaccinations.

And on and on.

Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Different from the above, but I need to include the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (conducted from 1932 – 72). This study was a major ethical fail, created to study untreated syphilis. The US Public Health Service told African American men in the study that they were receiving free health care rather than being treated for the disease. After the study was exposed, the result was enduring mistrust of healthcare services by the African American community. This study was different from the above examples in that its purpose was secret rather than spreading disinformation. Its impact was felt decades later in the HIV / AIDS beliefs referenced above.

Coronavirus. Being a new, international disease has offered opportunities to those trying to intentionally spread disinformation.

Similar to Operation Infektion above, the SCMP reports that Russian work has also contributed to “conspiracy theories that the United States is behind the Covid-19 outbreak.” This impact hits parts of the world with weaker health systems and low levels of trust in local systems. From the same article, the “US believes the latest Russian disinformation campaign is making it harder to respond to the epidemic, particularly in Africa and Asia, with some of the public becoming suspicious of the Western response.”

Emerging disease disinformation and misinformation techniques

Where could we expect disease disinformation techniques to move in the future? Here are some thoughts.

- Targeted disinformation attacks on specific countries or groups of people, managed via bots and organized individuals.

- Misinformed attacks on countries or groups of people. Some claim that the coronavirus epidemic gained extra attention because of a bias against China.

- Misunderstanding statistics. “The seasonal flu that receives no extra attention actually kills more people,” they say.

- Disinformation attacks without political goals, just chaos goals.

- Use of persuasive bots to target people at scale, learn from reactions, and move public opinion.

- Not wanting your family members bad outcomes from a health treatment to be just a statistic. There will be bad outcomes from vaccines as well as coincidental outcomes that seem to be related to a health treatment.

- The return of Emergency Broadcast System-like public service announcements and the hijacking of these systems. A recent riot in Ukraine against a bus of people returning from Wuhan was in reaction to a fake email that looked like it was sent from the Ukrainian health authority.

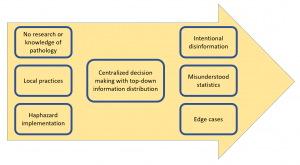

The historical progression (below diagram) of decentralized thinking about disease, to centralized, to a different decentralized form is where we may be now.

Consider

- The Vaccine Confidence Project monitors public attitudes, creating an “information surveillance system for early detection of public concerns around vaccines…”

- The interplay of centralized decision making about treating diseases with the decentralized way people receive information about diseases.

- Is there any international group that contacts website owners to take down false information about diseases? Seems like legitimate publications referenced above, like the BBC and The New Scientist, would want to remove their outdated information. I believe that this is a situation where the publications are not aware of this old incorrect content rather than not having a process for its removal.

- Some disease treatment decisions are beneficial for the group, others for the individuals.

This is Part 3 of a coronavirus series. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 4, and Part 5.