As a rule, I don’t cover breaking news on this site. Plenty of other sources do that. Instead, when I do write about current events I focus on looking at the effects that systems have generating unintended consequences. That’s why I’m only writing about the Wuhan novel coronavirus now, almost at the end of the declared 14-day lockdown period.

And what a story of systems.

While the novel coronavirus fatality rate is estimated at 2.2% versus 9.6% for SARS, some other qualities of this outbreak may make the illness more difficult to contain, namely the long period of incubation (14 day estimate) and the increased amount of travel, including international and domestic Lunar New Year travel shortly before the lockdown period.

If you want an example of how times have changed since earlier epidemics, watch this video from the English publication of China’s People’s Daily.

Walking around without a protective face mask? Well, you can’t avoid these sharp-tongued drones! Many village and cities in China are using drones equipped with speakers to patrol during the #coronavirus outbreak. pic.twitter.com/ILbLmlkL9R

— Global Times (@globaltimesnews) January 31, 2020

I’m usually not one to quote from a publication like Global Times, but this video is just too good. Using drones to call out people going outside and without masks… it’s simultaneously funny, futuristic, and freakish.

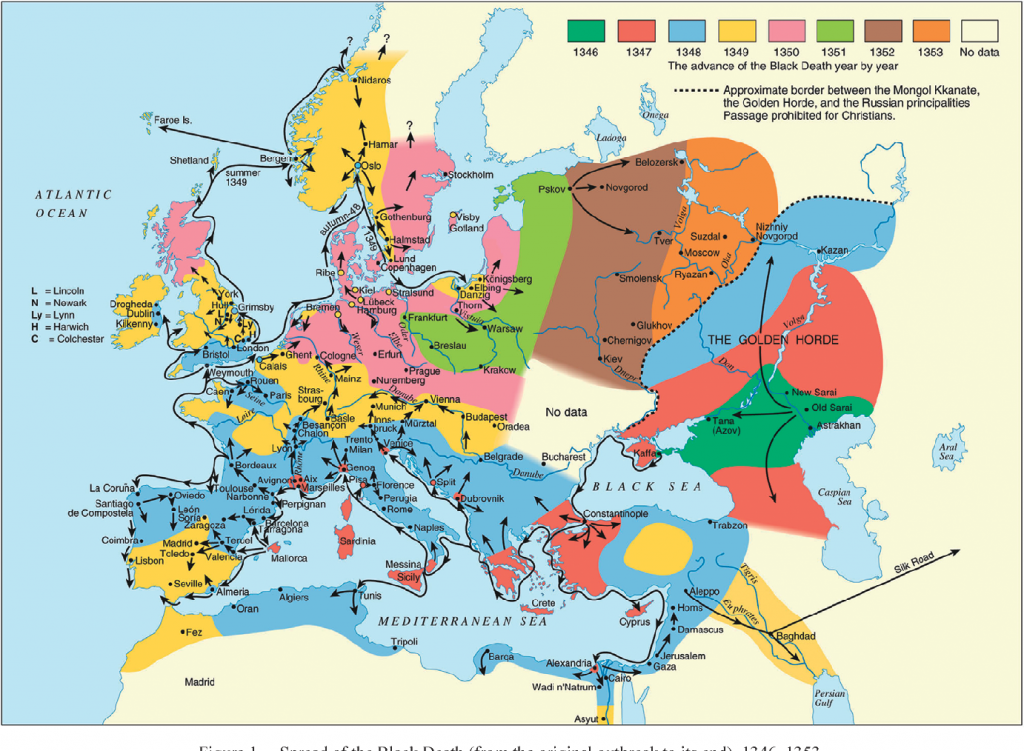

The lockdown. Why lockdown a city or quarantine travelers? The practice of quarantining (from the Italian “quaranta,” meaning 40) people and animals was adopted in Venice in the 14th century through a 40 day delay of when people from new ships could enter the city state. At that time there was no real medical care for those affected with plague, so physical separation from the healthy was the only practice that worked.

Even without an official quarantine, some people did so themselves during times of plague, as famously described in story The Decameron.

Consider that China’s ability to propose and then enforce a lockdown of Wuhan city, other cities, and then Hubei province is unusual in the world today. Had this coronavirus originated in some other connected part of the world, there probably would have been less ability to respond with a lockdown.

by Deneb Cesana, Ole Jørgen Benedictow, and Raffaella Bianucci

- Includes animal vectors (rats, fleas).

- Different standards of cleanliness, less human-animal separation keep transmission high.

- Carried via travelers and animals entering port cities. Travels thousands of miles over months or years.

- Incubation period of 2 to 6 days.

- Affected populations mostly reliant on local supply chains

- Includes animal vectors (possibly bats).

- Higher levels of cleanliness and mask wearing.

- Transmission via travelers entering today’s more numerous port cities. Faster travel. Travels thousands of miles over hours or days.

- Incubation period of 2 to 14 days (estimated).

- Affected populations have large exposure to global supply chains

Speed and commonality of travel. This is one of the most important points from the comparison above. Even with the greater cleanliness of today, the volume of travelers and speed of travel mean that that extra cleanliness can be quickly overrun. Greater transport links and speed of travel mean that even with China’s city-wide lockdowns, the coronavirus has spread widely and quickly.

Comparing the Wuhan coronavirus with SARS, another recent outbreak that also originated in China, we see a very different picture of international travel. As a rough comparison, there were 160,000 visitors from China to the US in 2003, during SARS. In 2019, 2.8 million visitors from China went to the US. While the lockdown has now slowed travel, the possibility for unintentional transmission to faraway places is much greater. International (and domestic) travel is so much more common today.

Incubation period. With an incubation period of up to 14 days, a carrier could infect many others without knowing it, especially since combined with the ease and speed of travel. Other illnesses had shorter incubation periods, which improve the odds of identifying someone infected before they travel.

As I wrote in Systems for Spreading, differences such as incubation periods matter a lot in the spread of disease. In the case of the long 14 day incubation period and uncertainty about how this coronavirus is carried, separating potentially infected populations can slow down the speed of spreading.

Fallacy of Cost – Benefit Analysis. Some may consider the cost of quarantining people in Hubei province and elsewhere and of restricting flights. However, as I wrote in Should We Reevaluate the Precautionary Principle and its application during the Fukushima nuclear disaster:

“After Fukushima there was a 40% increase in electricity prices in parts of Japan more highly dependent on nuclear energy and even a 10% increase in areas with low dependence. The authors then calculated that these higher prices changed consumer behavior and so the “higher electricity prices resulted in at least an additional 1,280 deaths during 2011-2014…’ The number of deaths from cold then was higher than that from the nuclear disaster.”

That’s the calculation in retrospect. In the moment, we have no idea how an epidemic will play out. Only that if we don’t stop travel we will undoubtedly contribute to the spread of the disease. Will the cessation of travel prove worse than the benefit? We won’t be able to guess until later.

Some studies show that in past outbreaks, travel bans had no impact on outcomes. But that conclusion doesn’t account for the likelihood of unpredictable outcomes. As I also wrote in Should We Reevaluate the Precautionary Principle:

“When presented with an uncertain future where there is an approaching uncertain risk of large chaotic negative outcomes or one where there is more certain likelihood of stable negative outcomes, choose the latter.”

As reported in the article In Attempt to Curb Spread of Coronavirus, Chinese Tourists Turned Back at Tel Aviv Airport — “Health Ministry Director General Moshe Bar Siman Tov said ‘We believe it is impossible to prevent the virus from making it to Israel, but we’re trying to delay it as much as possible. When it does happen, we’ll know how to handle it.”

Cleanliness. Hygiene was very different in the past. In 16th century Europe involved rubbing the skin with dry linen and using perfume. Washing was primarily applied only to the hands and face. “Washing with water is bad for the sight, causes toothache and catarrh, makes the face pale, and renders it more susceptible to cold in winder and sun in summer.” (from La Civilite nouvelle contenant la vraie et parfaite instructure de la jeunesse).

There were also very different beliefs on where pests come from and why they are just part of the natural order of things…

“What are the fruits born of us? The… fruits which we produce and which are born of us are the nits, fleas, lice and worms which are created by and in our bodies and are constantly growing there.” (14th century text quoted by J. Delumeau, Le Peche et la Peur.)

Much attention has now been given to Chinese standards for cleanliness in markets. Just like the earlier SARS outbreak led to the common practice in China of people wearing masks when they are sick, it is likely that the Wuhan coronavirus forces better standards of food cleanliness.

Complex, far-reaching supply chains. Many businesses that came to rely on China-based producers will be forced to rethink this practice, even if there are no other immediate options. The interesting twist is last year’s often misquoted tweet from Trump where he wrote “Our great American companies are hereby ordered to immediately start looking for an alternative to China…” You can like or dislike the person, but you can’t disagree with having alternatives. Many international businesses are realizing their exposure to a single country of production as Chinese factories may not able to produce at the speed they could earlier. The novel coronavirus will force companies to plan to move some production outside of China.

Other local production. Related to the above, being able to fall back upon local production, at least for a time, is a great advantage. The most isolated places in the world are the least at risk to coronavirus. If you live in, say, North Sentinel Island, you never need worry about coronavirus infection.

As I wrote about that isolated island (in A City Too Familiar):

“The Sentinelese are right to enforce their isolation. They have survived their long isolated history (also certainly due to location, policy, and luck) and their survival shows that their strategy has been correct. Varying from this strategy will be very tricky.”

For most of the already connected world, this extreme tactic of total isolation would be more painful than beneficial. But the ability to survive on locally produced foods and supplies is something within reach of many parts of the world. Will coronavirus push more locations toward local production?

Travel businesses. Airlines, tours, and hotels, are slashing financial projections, as they did after 9-11. As above, if your business relies on customers from far away, what happens when they can no longer travel? Hong Kong tourism businesses and European luxury goods companies are highly exposed to the ability of Chinese citizens to travel. These businesses also grew greatly because of that travel ability. So in this area, we’ll see a whipsaw effect — lots of growth in good years and lots of decline in bad years.

Ethnic discrimination. In the past, when travel was not common, for example during the plague times of the middle ages, identifying travelers or outsiders was easier. Today, simply assigning infection to anyone who looks Chinese can backfire, for example:

#Coronavirus On a train in Italy. A teenage Chinese boy boards the train. A woman comments loudly: “There you go, we are all going to be infected.” He replies in perfect Italian with a Roman inflection: “Ma’am, in my whole life I’ve seen China only on google maps.”

Applauses.— Tommaso Valletti (@TomValletti) February 1, 2020

Centering blame on outsider groups has a long history. As an historical callback to the above example, in the US during the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, “[r]umors spread that the epidemic had been brought by immigrants from Italy to the United States rather than contracted here by the newcomers. Some, including visiting nurses… were angry and impatient with Italian immigrant families.”

Another version of coronavirus blame is based on Chinese eating practices. A viral video of a Chinese social media influencer eating a bat recently caused outrage. However, this video was from years ago and filmed not in China, but in Palau.

Political impact. I have written about the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) in earlier posts, including its novel use of technology for top-down control. While there are technological ways to control populations (restricting communication access, shutting off finances), control depends on being able to also show physical force. But when a volume of critics is passed, how can the CCP respond physically to so many people? That’s perhaps why we’ve seen more videos critical of the Chinese government response — resources are already occupied elsewhere. Will the coronavirus produce a volume of government public criticism not seen before?

This video from a man in Wuhan China (or at least claimed to be) is the type that got people in previous articles arrested at home. Will “freedom” to complain reverse after the epidemic is controlled?

“In some countries, the suspension of personal liberty provided the opportunity—using special laws—to stop political opposition…. In the Italian states, in which revolutionary groups had taken the cause of unification and republicanism, cholera epidemics provided a justification (i.e., the enforcement of sanitary measures) for increasing police power.” — Lessons from the History of Quarantine, from Plague to Influenza A

There is even precedent for controlling information flows about the spread of disease. During the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-19, the “most influential newspaper in Italy, Corriere della Sera, was forced by civil authorities to stop reporting the number of deaths (150–180 deaths/day) in Milan because the reports caused great anxiety among the citizenry.” — Lessons from the History of Quarantine. (The Spanish Flu itself took its name from a neutral country in Europe that did not censor news about the disease.)

Ironically, the political impact on Hong Kong may be different. Hong Kong’s protests of the last six months produced public gatherings in the millions, ironically with many also masked, but in order to hide their personal identities. Will people no longer gather in these large protests due to the coronavirus spreading in Hong Kong?

Boosts to healthcare and related processes. Greater global connectivity means that some disease precautions will outlast the epidemic. Even food delivery (necessary since people aren’t supposed to leave their homes) may see lasting impact.

Food delivery note in Beijing now. The food preparer, packer, and the courier all have to measure their temperatures. pic.twitter.com/u2GZQkdgEA

— Steve Hou (@stevehouf) January 31, 2020

Remote work. I’ve already had an international meeting reschedule because of coronavirus impact. Will remote work become preferable, not for convenience, but for safety? Some types of work (retail, some manufacturing, transportation, restaurants, bars, clubs, education) are impacted by the ability to gather in person. Other work types (software development, design, some research) will be less affected.

Consider

- None of the above were more than theoretical examples a month ago. Things change fast in a connected world.

- The impact of disease — either attempts to control epidemics or new safety practices — will have an outsized effect on our future.

- I wish all readers (and non-readers) well!

This was Part 1 of this topic. You might like to read Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.