This is a continuation of the Universal Basic Income (UBI) discussion, mostly focused on the impact on entrepreneurship and personal choice of what work-related activities to pursue. (If you missed it, here’s UBI Part 1.)

As in the previous posts, I think we should pause in the face of large top-down decisions. While things can look good in theory, these large-scale changes often bring unintended consequences. How should we look at the systems we will replace? Might there be second-order effects in the case of UBI as well? What system changes will emerge?

What are some entrepreneurship-related unexpected results we could see from top-down UBI in the US?

While people disagree on whether or not to enact UBI, and how, one thing there is agreement on is that the topic deserves attention. Better to think about the oncoming issue of automation-fueled job loss now than to delay until the situation is worse.

It’s an interesting change in historical perspective. 15 – 20 years ago we were more concerned with offshoring — getting rid of higher-paid domestic jobs — for cost savings and stock market benefits. Back then McKinsey famously argued for offshoring as a net positive within the US, even referencing the 3.4 million jobs estimated to be lost. The argument included statements showing reduced costs and redeployed labor.

Automation, like offshoring, brings different costs and benefits to different groups. The upside of businesses that benefit from those changes in cost and production is not the same as the downside of those who no longer have jobs. Some things may become cheaper to buy, but people also have less income.

So the UBI argument of today is different from that of the past. 50 years ago President Nixon proposed a form of UBI with support from Senator Daniel Moynihan and economist Milton Friedman — initially without a work requirement (though that had to change for broader political support). Thomas Paine supported UBI 200 years before that. I introduced their support in the previous UBI post.

Those earlier arguments weren’t based on the risk of job loss from automation, a concept which didn’t scare people like it does today. Those arguments were based on providing a social safety net. Income as a right.

But the argument for UBI as a social hedge against job loss also sounds like something else — a third-party candidate’s catchphrase from the 1992 presidential debate. It was a discussion about offshoring job loss from NAFTA and globalization back then, rather than automation.

“We have got to stop sending jobs overseas… If you’re paying $12, $13, $14 an hour for factory workers and you can move your factory South of the border, pay a dollar an hour for labor, … have no health care—that’s the most expensive single element in making a car— have no environmental controls, no pollution controls and no retirement, and you don’t care about anything but making money, there will be a giant sucking sound going south…. when [Mexico’s] jobs come up from a dollar an hour to six dollars an hour, and ours go down to six dollars an hour, and then it’s leveled again. But in the meantime, you’ve wrecked the country with these kinds of deals.” — Ross Perot, second 1992 US Presidential Debate

Unlike that argument, which was about whether to encourage or discourage sending jobs outside of the US for corporate financial benefits, the job automation argument is different. For one thing, no one seriously suggests trying to slow down the move to automation, as stopping or delaying a trade agreement would have done. Instead, a common view is that job automation will first take the hazardous and mind-numbing jobs, such as low-skilled factory work, certain types of manual labor, transportation, and repetitive business processes.

But what if that’s your job? And what if the other job options you have are worse?

Entrepreneurship

I’ll hold off on the question: “why do we want more entrepreneurship?” to focus on the impact that UBI might have.

One item we’ve mentioned in past posts is the size and impact of higher costs of education. College tuition and fees, noted in the first post as being up over 150% in 20 years.

Student loan debt has been shown to be negatively correlated with entrepreneurship, at least small business formation. It makes sense. What wasn’t risky becomes risky when you have higher fixed monthly expenses. So one of the UBI arguments is that monthly payments will take away some of the pain of student loans. (The big, and I think faulty, assumption is that the universities and lenders won’t increase tuition and rates even further.) That monthly UBI buffer could increase the number of people who take a chance and start a small business.

But with automation there will also be businesses that become better or worse to run without considering UBI. Entrepreneurship is about risk minimization and so people starting small businesses at great risk of automation would be throwing good money after bad.

What are the business types that will benefit from UBI? Let’s compare two traditional small business types — a barbershop and a restaurant — in the framework of job automation.

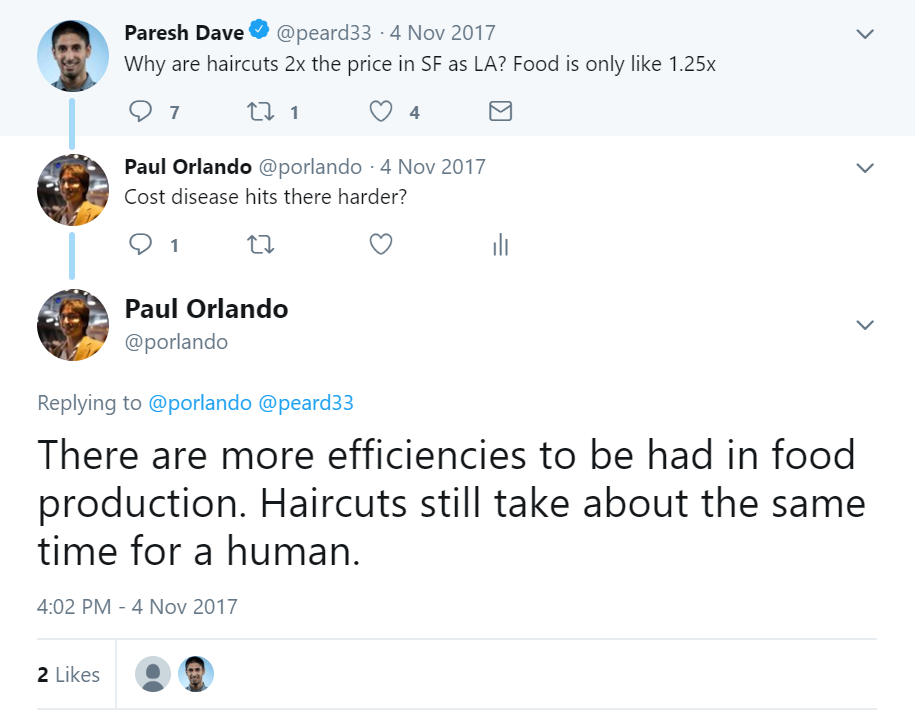

The barbershop / hair care. These are jobs that are less likely to be automated for a while. But the problem is, at least currently, each haircut takes the same amount of time. Until we have robot barbers. Or until there’s a human-operated machine that people want to use that completes a haircut in a minute. Without that, barbershops can’t become more efficient (just like a previous post mentioned learning to play the violin).

The restaurant / food service. On the other hand, there are many ways to improve food production.

- Certain processes become automated. Past production improvements would have been machines that do the work of humans — cutting, blending, packaging.

- Productization. The food product becomes a replicable, mass manufactured product, from Sriracha to Soylent.

- Manually producing but increasing the volume produced. Making a giant pot of chili 10x the size of a small pot doesn’t take 10x the time or work.

- Focusing on production and doing delivery. Maximizing space used for production. Setting up demand in advance.

So a question of which businesses win after UBI’s introduction comes down to which ones benefit more from automation. Winning from automation can include those that survive automation, like the barbershops above. Will UBI plus automation result in more business formation of the type where human labor is not easily automated away?

Remote Work or Just Remote

Of the work types that exist today, remote work will gain from UBI — also in areas at low risk of automation. It’s an arbitrage play that UBI will allow and that recipients should seek.

The UBI argument is the assumption that monthly payments will be enough for people to do something they want, but not really enough to do nothing. That can change when UBI recipients move to inexpensive areas that allow them to live just off their monthly payments.

There are parts of the US where a couple without kids (no UBI payments until age 18) could live (though maybe not comfortably) on $2,000/month that is also supplemented with minimum wage jobs. I assume that healthcare expenses aren’t a factor here (big assumption).

Another effect that UBI could produce is an international population shift. A large population now receiving UBI chooses to go abroad in search of cheaper, and yet fun, living arrangements at under $1,000/month. The hindrance to this happening before UBI is the need and difficulty of receiving employment visas to fund long-term travel. This need not be the case anymore. A difference could be that these new transplants might be more representative of the US population.

So if a significant population pursues that option after UBI, it could mean many other places, domestic and international, will be affected. Similar to the price impact wealthy international property buyers had in international cities, relatively poor UBI recipients could impact other locations when they travel at scale.

Cheap, low populated domestic locations may benefit from people moving in. Would some high-demand international destinations want to attract Americans with UBI as well? I can see international hostels and educational institutions putting together all-included packages that fit within the $1,000/month budget. And would other locations want to prevent large numbers of visitors (as with Venice and tourists or resort towns with Airbnb)?

Considerations

- Tests of UBI are small-scale today, as expected. How will impact of UBI change when rolled out nationally?

- Proponents of UBI often have political goals or philosophical beliefs. What happens if the data they receive from the local UBI tests don’t support their views? Change views or reinterpret data?

- Since UBI may be funded through a Value-Added Tax on goods and services, what happens if the international relocation affects the ability to fund UBI itself?