I’ve avoided discussing unintended consequences from one of the big policy debates of today — Universal Basic Income. Until now. This is a big topic so I preemptively titled this post as part one.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is a general term that describes mostly government programs that distribute a periodic sum of money to citizens without otherwise considering their income. UBI has been proposed as everything from a tool to reduce poverty to a way to guard against the social impact of job loss caused by automation.

Each group outlines ways UBI could work a little differently. But many questions remain, including how will a particular country’s overall social system change? What are the second-order effects? Could UBI work in one place and not another? Could UBI work at one time and not another? Let’s first look at some UBI experiments and their initial pros and cons.

As you’d expect, I’m cautious of large-scale top-down programs.

The U in UBI is for universal. That is, everyone receives that basic income, regardless of their income level or overall wealth, unlike other social programs. UBI is for everyone (or at least citizens) within a nation’s borders.

This type of payment has been tested locally in quite a few places. But how the overall system will change once everyone has a UBI is the biggest unknown risk. Also, reversing UBI once people depend on it would probably be incredibly disruptive.

We don’t know how things will change across generations. We don’t know, for example, if later generation UBI recipients will act differently from first generation UBI recipients. But UBI experiments depend on positive effects to convince others of the programs. I call this the Lei Feng effect, named after the legend of a selfless (and mostly fabricated) young soldier who was portrayed as a model citizen in post-revolutionary China’s early years. For some time after instating UBI, positive effects may be seen — you’re going from nothing to something. But after those effects wear off, what happens? While he was initially an inspiration, Lei Feng later became understood as a story, and kind of a joke.

Once you start down the UBI path and people expect and depend on UBI, changing or reversing direction would also be incredibly disruptive. Political backlash will probably prevent that as long as possible.

Painful transitions from large-scale income and work shifts are not new. For example, over the past century in the US (and other regions), many people transitioned from self-employment or working for small artisanal employers, to be employed by large organizations. It was the emergence of the job. It became less common to work with family members and at home.

As jobs were popularized, after the first generation of workers saw incomes pushed low, organized labor helped push up incomes for certain types of work. It was the first time many families could be supported by a single earner. This wasn’t everywhere, but was common in large parts of the US.

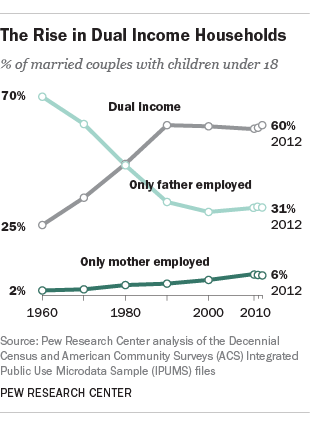

That change has mostly reversed. Afterward, growth in dual income families created new problems (such as added expense for child care and education), as it solved other problems (possibility for women’s independence and fulfillment through work).

It is now less common or likely that a single earner can support an entire family in the US. While movement toward self-employment and alternative types of work might be more “American” in style — that is, more people are left to fend for themselves — it also makes life difficult for many people. The other trends that accompanied that shift include fast rising costs of education and healthcare. This graph highlights much of that.

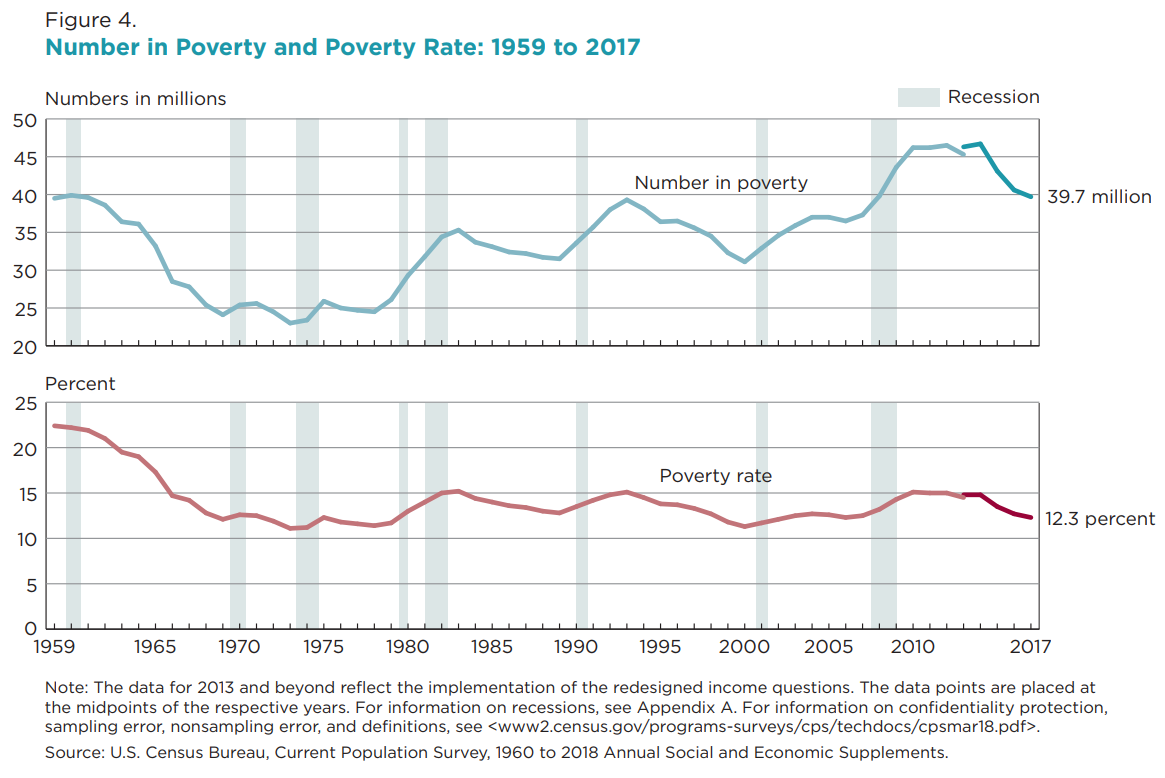

The population in poverty has trended downward but remained pretty flat as a percentage for the past 35 years. Many believe poverty rates will raise dramatically due to automation.

UBI distributing $1,000/month would eliminate poverty in the US, as defined at current thresholds.

A glance at UBI programs

Here’s a short list of past and current UBI experiments.

Nixon’s plan. President Nixon looked into a form of UBI in the early 1970s. As detailed by the NY Times in 1973, Nixon’s plan was different from current UBI experiments in that his plan included “work requirements and work incentives.” Nixon’s plan stalled out from lack of political support.

Alaska. The approach of the Alaska Permanent Fund is different. The state pays its residents an annual dividend based on state oil revenue investment, generally ranging from the hundreds to $2,000 per person.

In the state of Alaska, poverty rates “fell from 25% to 19% between 1980 and 1990,” though the national poverty rate also fell similarly during this period. In the quoted article, “[o]nly one percent” reported working less because of the annual dividend. Is the self-reported data accurate? Does one percent make a difference?

Finland. A two-year experiment (2017 – 2018) with 2,000 unemployed people each paid 560 Euros/month (about US$630). Participants were kept in the study even if they found employment during the two years. The study was interested in UBI’s effect on “income, well being and employment status of the participants.” Results will be released over 2019 and 2020.

Y Combinator (YC). YC has a small trial planned, where individuals will be randomly selected to participate. I like the approach which, like Finland’s, is based on learning and experimentation rather than theorizing. As YC states in their proposal: “Interest in basic income has recently skyrocketed, but the debate often relies on conjecture, stereotypes, and studies that are out-of-date, methodologically flawed, or from disparate contexts. This lack of data and experience impedes rigorous policy analyses and data-driven political debate.”

YC has already run two smaller versions of the UBI experiment, but will follow up with a larger group of 1,000 people receiving $1,000/month over three years. The experiment will study impact on time use, subjective well-being, and health, mental health, and cognitive functioning, among other qualities.

Andrew Yang’s proposal. Andrew Yang’s proposal for UBI is one of many, but since he’s running for president I decided to look into it more. Like YC’s plan, Yang believes that automation will destroy jobs and leave millions unemployable. His UBI proposal is funded through a new Value-Added Tax (VAT) on all goods and services. I don’t yet have a handle on how the math works nationally and over years. The proposal assigns all US citizens $1,000/month, without restrictions on income level.

The system is not the system

I wonder how we can best maneuver through the UBI puzzle. Any system is subject to change. Systems that worked well at one point can stop working if other factors change. I do not believe that anyone has a handle on this when it comes to UBI.

I agree that small tests are a way to begin experimenting. But rolling out UBI to small trials of individuals (UBI without the U) is not the same as rolling out UBI to an entire nation. How big does the test need to be? Or is it even possible to test UBI before national rollout?

An obvious criticism of UBI is that receiving something for nothing disincentivizes working. While I don’t believe that effect has been seen in the short-term small scale trials, that doesn’t mean the criticism is not valid. National UBI has also been compared to qualities of communism, including China’s past “iron rice bowl” policy. While in effect, the incentive to work hard is removed. When it is discontinued, the transition can be painful for less employable people.

Sovereign wealth distributions are used elsewhere, also with questionable results on willingness to work. Some petrostates (for example Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, and also Iraq in the past) provide forms of free or subsidized commodities (food, fuel) as well as some guaranteed employment.

So my largest question remains: how to test UBI before committing to it and possibly creating even bigger problems?

Considerations

- The current small-scale tests are a start but do not represent the system when everyone receives UBI. Something unexpected about the overall system is likely to change when UBI is rolled out at scale.

- The individuals that currently are part of small UBI experiments are better off than their neighbors for it. Does this effect diminish when everyone receives UBI? Temporary, local tests do not represent the system when everyone receives UBI for life.

- Would UBI also weaken other social programs already in place? If so, will these social programs argue against UBI?

- What transferability and advances will be possible? For example, today advance paycheck cashing is a large industry that provides liquidity at a cost for people who need it. Perhaps we will also see advances on UBI payments? What other businesses will emerge to benefit from the timing of UBI payments? Student loan repayments built around UBI?

- The larger population must be comfortable with perceived recipient misuse of UBI payments. There is enough discomfort today just with the small population of welfare receipts.

- How does UBI impact the shadow economy? What impact will it have on drug addiction, for example?

- Between eliminating and replacing something there is another way, which I call “elimitigation,” (after “eliminate” and “mitigate”). How could we build a UBI system from the ground up rather than the top down?

- Could something else be done to create income and improve work/life fulfillment without UBI?

- The poor will always be with you…?

(I also wrote UBI Part 2.)