Apart from the US presidential election, another well-funded campaign from 2020 was California ballot measure Proposition 22. If you live outside of California, you may have never heard of Prop 22, even though it could come to impact you.

Prop 22 was a California referendum that dealt with a question specifically addressed to rideshare and app delivery companies. Namely, should rideshare drivers legally be considered contractors or employees?

Now that attention to the presidential election and inauguration has past, let’s go back to look at Prop 22, its Yes vote, and how its implementation led to a system change.

The Fallout

Less than a month after Prop 22 came into effect, related companies took the following actions:

- Albertsons grocery stores including VONS and Pavillions laid off their delivery people to replace them with gig workers.

- Instacart cut 1,900 employee (not contractor) jobs.

- Political Action Committees have formed to bring Prop 22-style legal changes to New York, Illinois, and perhaps nationwide. And possibly globally.

This is just the beginning, but each of the above outcomes have been met with some amount of shock and outrage. Why now?

The Ballot

What Proposition 22 actually said on the voter guide:

“Prop 22: Exempts App-based Transportation And Delivery Companies From Providing Employee Benefits To Certain Drivers. Initiative Statute.

“Summary: Classifies app-based drivers as “independent contractors,” instead of “employees,” and provides independent-contractor drivers other compensation, unless certain criteria are met. Fiscal Impact: Minor increase in state income taxes paid by rideshare and delivery company drivers and investors.”

As with many ballot propositions, it took lengthy explanations to show what voters were actually choosing. Rather than list all the listed arguments and rebuttals here, see the lengthy voter guide for the full details voters received.

Set aside the reality that few voters may actually read propositions carefully. Also set aside the issue that common knowledge of Prop 22 probably came more from ad campaigns than language listed on the voter information guide. To me, the most noticeable information was the information missing from the information provided. How would rideshare and related systems change if Prop 22 received a Yes or No vote?

The Campaign

Prop 22 put the business models of rideshare and delivery companies at risk as well as threatening to change gig worker treatment. The risk for either side was in their relative change. What followed were ad campaigns in support of either side.

But a ballot initiative doesn’t require that both arguments would be heard equally or presented just as well. Rideshare and delivery companies (Uber, Lyft, Postmates, DoorDash, and Instacart) spent approximately $200 million promoting a Yes vote. The opposition spent only $20 million.

How should we judge spending on Prop 22? To compare, in the last couple decades, we’ve seen dramatic increases in fundraising for presidential campaigns. In 2000, Bush and Gore together raised around $450 million. Another contentious presidential campaign in 2004 saw the campaigns raise $1 billion for the first time. For the record-breaking 2020 campaign, Biden and Trump collectively raised $1.7 billion (counting all the other candidates would double that amount).

Of all the 2020 presidential campaign money, $288 million came from donors in California. That gives us some perspective.

So perhaps the $220 million spent on Prop 22 in California makes this single issue similarly important to a presidential campaign. The financial support is different though. Companies backing the proposition can model their own benefit to the point that they know what a win is worth. That’s harder to do with a presidential campaign.

App companies also had distribution on their side. That is, they already had a direct line to customers and gig workers and could push messages like this.

Uber later updated the popup as follows.

Is it possible that 72% of drivers supported Prop 22? With that majority, shouldn’t voters follow the drivers?

This is where you might use the phrase “lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Uber drivers have different needs. Few regularly work over 15 hours a week just for Uber (the minimum needed to qualify for the Prop 22 benefits) while many work fewer hours and also split their time between other gig companies. Those in the second category would likely lose their ability to drive for Uber in the event of a No vote that classifies app workers as employees. That could explain why so many Uber drivers and delivery people supported the proposition.

The vote passed 58% in support of Proposition 22.

Comparisons

We need to back up a moment to an earlier bill. Prop 22 was itself a follow-up to Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), a 2019 bill which provided a three-part test to whether someone is an employee or a contractor.

The AB 5 bill’s three requirements (the ABC test) are as follows:

- “The person is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact.

- “The person performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business.

- “The person is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed.”

AB 5 also granted numerous business-type exemptions, but not to app companies.

Exempted businesses were notably not individually well-funded or from Silicon Valley, though they may have held political sway with California legislators. These AB 5 business exceptions include doctors, dentists, lawyers, architects, engineers, accountants, commercial fishermen, designers, artists, barbers, and more.

They political sway was most allegorically seen in business awards a legislator bragged about for writing exemptions into AB 5.

I never imagined that my only “gold record” would be a thank you from the Recording Industry Association for working to right-size Dynamex & AB5 for musicians. But, I’ll take it! (Have you heard me on Karaoke though??) pic.twitter.com/OUfiDcPD4i

— Lorena Gonzalez (@LorenaSGonzalez) October 30, 2020

AB 5 threatened the gig economy business model where drivers, delivery people, and other workers did not receive employee benefits. That threat was bound to receive a response from the companies that had the most at risk.

But how was Prop 22 described? From the Los Angeles Times:

“The ballot measure would require the companies to provide an hourly wage for time spent driving equal to 120% of either a local or statewide minimum wage. It would not pay drivers for the time they spend waiting for an assignment. It also requires that drivers receive a stipend for purchasing health insurance coverage when driving time averages at least 15 hours a week, a stipend that grows larger if average driving time rises to 25 hours a week.”

This is an example of where it’s difficult to assess outcomes from a quick read.

15 hours might sound like a low bar, but this is active driving time. Potentially double that amount of time to include driver wait time between fares. Also, the active driving time is tracked per company. That is, 10 hours driving for Uber and 5 hours driving for Lyft do not qualify as 15 hours. Just meeting that 15 hour minimum will prove difficult for many drivers.

Further, an earlier analysis of Prop 22 by the UC Berkeley Labor Center reassessed the 120% of minimum wage benchmark ($15.60) and claims that drivers with more than 15 active hours per week would actually earn only $5.64 per hour.

Why would drivers choose to work if their pay declines? There could be a number of reasons, including that they prefer driving to other work and can’t find other work. A distinction of gig economy work is that you typically don’t need to commit to a fixed schedule. In the case of driving for rideshare delivery businesses, gig workers can work just about any hours they want. That flexibility may make up for their ability to earn more doing something else.

Rideshare companies are famous for having basing their distribution model on moving into new municipalities in advance of any legal right to do so. Uber entered the New York City market without a license to operate as a transportation company. As a result, taxi drivers felt both their fares and medallion values fall and riders benefitted from lower fares and more supply.

A No vote on Prop 22 was supposed to challenge not the distribution part of rideshare businesses, but their cost structure.

But after the Yes vote, some fees have also been passed on to customers. For Uber and Lyft, the fees depend on location and range from $0.30 to $1.50 per ride. Postmates now charges a driver benefits fee of between $0.50 and $2.50, depending on location.

Prop 22 Paradox

Why did we see public shock and outrage in January when affected companies fired workers, changed policy, and added fees? Surely Proposition 22 voters would have expected some type of negative outcome, however they happened to vote.

It’s probably more likely that many Prop 22 voters didn’t really think about negative outcomes. Either because their chief concern was on what positive outcomes they would see, that they didn’t believe themselves negatively affected by potential changes. or they just didn’t have the habit of thinking about trade-offs.

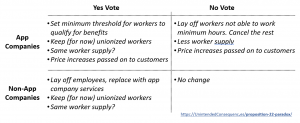

A look at Prop 22 outcomes.

Yes (drivers classified as contractors). Rideshare companies start to provide some benefits. Drivers continue to set their own hours. Price increases passed on to customers.

Other potential outcomes: Slower driving? Drivers have an incentive to reach 20 hours of active driving time. That’s the point at which benefits kick in. If the value of the benefits is greater than that from driving fewer hours, then drivers may slow down or at least not speed.

No (drivers classified as employees). Drivers receive pay increases. Drivers have to work fixed hours. Driver supply falls. Fares rise. Ride demand falls. Rideshare companies have difficulty operating in California. Price increases passed on to customers.

In the case of a No vote, affected companies estimated needed price increases of 25% to over 100%. Outside researchers estimated 5% to 10%.

Alison Stein, Uber’s economist makes this series of public projections for price increases, trips lost, and work opportunities lost.

Given Stein’s role we perhaps need to take the projections as one perspective. Notably, price increases are most extreme in the less populated parts of California (more inactive driver time between rides). But these price increases also stand out because Uber had subsidized rides to become a less expensive option than legacy taxis.

Trying to present the way a system change could have other outcomes is not unattainable. Especially in something like Proposition 22, which is relatively straightforward. I say relatively because unlike say electing an individual to political office, who might say one thing and do entirely something different, Prop 22 was more limited in scope.

It’s also not to say that putting out that systems map might produce one single correct answer. People can still weigh different outcomes differently. I just don’t like shock and outrage after a legal change goes into effect and companies act. The shock and outrage should have happened with the outcome of the vote itself.