It’s common for scalable companies with good business models to involve addiction.

I mean addiction in a broad sense. This includes addiction to both physical products and digital goods and services. Addiction is a retention metric.

And retention (how long someone stays a paid customer or user) is what fuels many businesses. Let’s look at this with opioid addiction, focusing on Purdue Pharma’s product OxyContin. What second-order effects drive the opioid crisis?

Addiction and business models fuel each other.

Take a large business for which most never pay: Facebook. Facebook has over two billion users (their term, not mine) who use the social network for free, often multiple times a day. Once subscribed, leaving Facebook for good is often too difficult. Too much of one’s life becomes intertwined with the network. Retention is measured in years. The service itself is engineered to be addictive, with notifications, presentation of new content, updates from friends, and more. There are many businesses that have achieved or are working toward something like this deep user connection.

Facebook also has customers — those companies that pay for access to the users. The key is to keep enough users active so that they will see (and click on) paid ads, generating revenue.

Everyone gets what they want. Facebook gets paid, the customers get access to users (who become their customers), and the users get connected, entertained, informed… But also sometimes persuaded, distracted, and confused.

Business models can tell us about the future of drug addiction.

But while the scalable business definition is usually used for tech startups, many of the same attributes (including high retention) apply in the case of opioids like OxyContin.

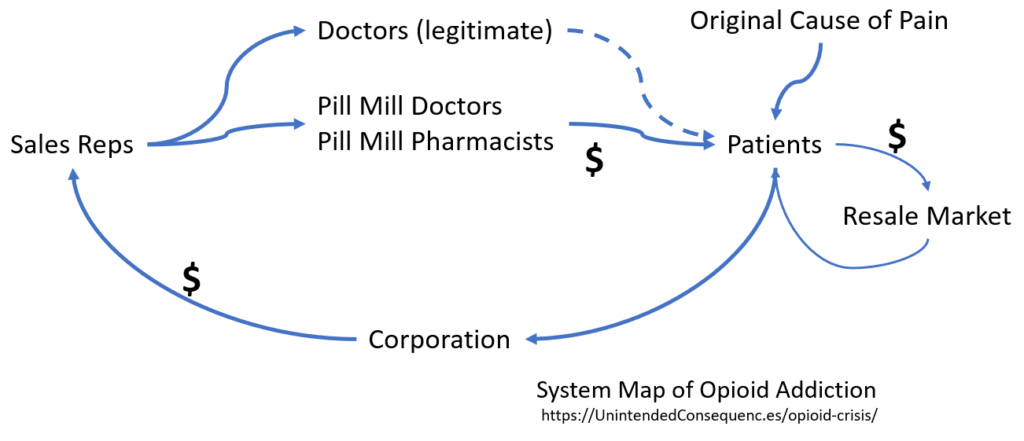

It’s when drug addiction and business models form a fast-turning, positive feedback loop that things quickly get out of control. This is a variation of the scaling effects I’ve written about earlier.

When I first looked at scaling effects, I did so in the form of what happens when there is change in availability of housing (Airbnb), change in global money flows (demand from China going to over-harvesting ingredients for traditional medicines), transportation (rideshare vs taxis), and tourism (over concentration of visits to top locations).

In the opioid crisis, there is a distinction in that distribution was more complex to start but perhaps easier to maintain once started. The unintended consequences were also probably easier to predict.

Purdue Pharma built a professional sales organization to convince doctors to add specific opioids to their list of prescribed medicines. Sales reps could earn significant bonuses by marketing OxyContin. “In 2001, in addition to the average sales representative’s annual salary of $55,000, annual bonuses averaged $71,500, with a range of $15,000 to nearly $240,000.”

The amazing thing to me is that there is a legal job function built around getting doctors to add a specific medication to their list — all done without paying the doctors in any conventional sense. No outright payments, but somehow, sometimes, the way to a doctor’s list of preferred medications can be through buying donuts.

Small Differences, Big Difference

It is the legitimacy of going through doctors that makes the effects of the opioid crisis seem different from other drug crises. This was not the case with other drugs — heroin for example, where the drug only reaches users through illicit means. Or even for drugs like cannabis that were illegal and are now being prescribed. The path to market for opioids like OxyContin was different.

Path to addiction. The path to opioid addiction can be legitimate. That is, doctors prescribed opioids in the past believing that the drugs were not addictive. That OxyContin had a legitimate path of market entry increased the number of users and changed the type of people who became addicts. A common path was to be prescribed opioids as pain medication, and then to be unable to move off of them. In some cases the people involved are not those otherwise likely to become drug addicts, such as this story about an engineer who becomes an effective bank robber to support his habit.

Also, “Purdue sales reps visited Massachusetts prescribers and pharmacists more than 150,000 times. Each of these in-person sales visits cost Purdue money — on average more than $200 per visit. But Purdue made that money back many times over… When Purdue identified a doctor as a profitable target, Purdue visited the doctor frequently: often weekly, sometimes almost every day. Purdue salespeople asked doctors to list specific patients they were scheduled to see and pressed the doctors to commit to put the patients on Purdue opioids… Purdue rewarded high-prescribing doctors with coffee, ice cream, catered lunches, and cash… Purdue used face-to-face sales visits to conceal its deception by trying to avoid witnesses or a paper trail. When one sales rep made the mistake of writing down in an email her sales pitch to a doctor, Purdue’s Vice President of Sales Russell Gasdia ordered: ‘Fire her now!'” — court document

Broad market base of addicts. While other medications have small, more specialized patient populations, the market for “pain” is huge.

Speed to addiction. Another interesting factor is in how much influence pharmaceutical sales reps could have on the way a doctor prescribed OxyContin and how that changed the likeliness of addiction. Part of this influence was on maintaining Purdue Pharma’s claim that the drug gave patients 12 hours of pain relief. OxyContin actually has a much shorter half-life for many people, leaving patients in a pain-induced state where they craved the drug before they were due to take their next dose. The 12 hour dosing could actually create addiction, according to Theodore J. Cicero and Peter Przekop (quoted here).

Resale value. The formation of “pill mills,” or places where gray-market doctors and pharmacists would write write and fill prescriptions with no questions asked kept the addiction problem going. Interestingly, while the pill mills had good gross margins on their sales (pills cost $0.30, sold for $10 each), they also left a lot of money on the table. Addicts bought pills at $10 each and then could resell them for up to $100 each. That markup at each point of the value chain made OxyContin profitable to distribute widely.

Comparing Opioids to Alcohol

Some comparisons to other addictions point out that deaths from the opioid crisis are actually fewer than those from alcohol abuse. So isn’t alcohol the problem to focus on?

This is a poor assessment of the situation for a few reasons, similar to the argument laid out in an earlier post on scale-related risks of autonomous vehicles.

First, compared to deaths from opioids, alcohol deaths are larger as a total number, but smaller as a percentage. (Not writing in estimated numbers here since the actual numbers vary as this is being studied.)

There is an ability to casually drink daily. Much less so the ability to casually take opioids daily.

Gateway for OxyContin users to switch to heroin which is cheaper and sometimes easier to access.

Most importantly, it would be difficult (impossible?) to dramatically increase the number of alcoholics or those dying from alcohol poisoning. To increase the number of opioid addicts or deaths from opioid overdose is easier to attain — increase your sales force.

Could Be Better, Which Could Be Worse

If the death rate of opioid addicts were not so high, this story might not be front page news. If it were impossible to take enough of the drugs to overdose, we might find an even more successful business model and one that could last much longer. If there weren’t a large corporation behind these drugs and the story thus lacked a villain, the visibility and impact might be different too.

How would a company design a drug, if possible, in order to avoid vilification?

- Make it highly addictive. High retention in the form of regular usage is the goal.

- Side effects don’t kill users. Or if they do, it takes many years during which the users can live normal lives.

- Side effects don’t prevent users from working, engaging in normal social interactions.

- Usage is social. Users reinforce their usage and even convert others to use.

- Distribution routes go through legitimate channels.

Go through that list and tobacco fits.

Consider

- There will be more drug related “crises” as more pharma companies figure out how to engineer addiction, possibly at safe levels, and how to build reinforceable business models.

- The path to building high retention business models in tech is supported by research into the development of addictive behaviors. Should these addictive products be judged similar to addictive drugs?

- How can regulatory speed be balanced with innovation speed? That is, how can drug approvals and the needed information about side effects and addictive properties balance against getting help to patients who need it?

- When there is a big market (like that for pain abatement), since the opportunity for abuse can affect more people, should the regulatory hurdles be higher?

- Could the cost of the risk of abuse be shifted to the drug producer’s senior management? That is, give the expectation that the default is for senior management to be held accountable if drug abuse passes a published threshold. Tying this responsibility to the company is problematic since spin-offs could be formed and shut down to minimize the risk. Assigning the risk to a group of specific people could have interesting effects.

- Look as the path from normal life to addict’s life as a conversion funnel that drives a business model. What businesses want you to be addicted to their products?