Are some things inevitable?

And if something is inevitable, what do you do if you don’t like it?

You could fight it indirectly and delay how fast the change happens. In that case, you will quietly subvert the system.

You could fight it directly, even though you will probably lose. In that case, you are fighting for honor.

Or, through a combination of luck and foresight you could build a system that shields you from the inevitable change taking over your corner or the world. In that case, you need to build and defend a boundary.

The Letter

The “Pause Giant AI Experiments” letter came as a shock to me. Not that someone wrote it, but that they wrote it yesterday.

Noteworthy signatories of that letter include Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, and a number of business leaders and academics. The list also included Andrew Yang, whose 2020 presidential campaign platform included AI-fomented Universal Basic Income.

But I disagree with the pause argument because the bubble of history seems already to have popped.

This has happened before. It was scary back then, too.

The most recent bubble of history (that is, a time of relative slow change) has been described in books like The Rise and Fall of American Growth. The authors point to the years 1870 to 1940 as a period of great inventions that fueled the modern era and the growth-based world we benefit from today. The time since 1940 has been a time of comparably less change than experienced before.

In the 1870 to 1940 period we saw the invention or popularization of transportation in railways, steamships, cars, and airplanes. We saw communications tech such as the telegraph, recorded voice, the telephone, the fax machine, radio, movies, and television. And we also saw the development of implements of war such as tanks, long-range bombs, and poison gas. Some good and some bad. Along with those changes came social changes as well, again, some arguably good and some arguably bad.

By comparison, the period after 1940 has been relatively slow. That is, until just recently you heard people who studied the issue claim that we don’t have enough growth, which seems strange. We are distant enough from that previous growth era that today we actually have a small radical degrowth movement. And then we even have (had) some wondering if that 1870 to 1940 era was a one-off improvement in the history of the world, unlikely to be seen again.

There is no consensus on this topic, though the issue of slowness is surprising to many people. “How could the world be changing too slowly? For decades everything seems to have been changing too fast!”

But whether the years since 1940 were changing too slow or too fast, another time of change is now upon us. And when there is change it wells up deep emotions. I like the “pre-nostalgia” framing another blogger coined. I can only look to history for clues to what earlier people did in related situations.

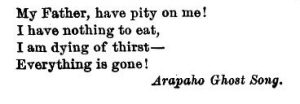

Ghost Shirts

In the 1870s Native American tribes were being pushed further onto other lands and their societies were falling apart. In a time like that, spiritual leaders emerged. One such leader was Wodziwob, who came up with a solution.

The various tribes were to perform a “ghost dance,” which Wodziwob described as the way to push away the white settlers and return the land to the previous, better era.

You can watch a video (from 1894!) of this dance.

The dances happened away from the settlers, but when they fought, some warriors wore ghost shirts, which were supposed to be impervious to bullets. They were beautiful, as you can see, but bullets went straight through them.

The book that sums up this era for me is The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890, by James Mooney.

The ghost dancers are an example of a group unable to deal with, unable to counter, and unable to accept enormous change, and then taking a religious approach. What is coming is so strong, so different, so inevitable, that the reaction is faith-based. A dance and a protective shirt.

For the 1870 ghost dance, Wodziwob spoke about the dead coming back to life and of eternal life for all Native Americans. His dance spread from Nevada, to California, and Oregon. It didn’t work.

The later 1890 ghost dance was revealed by the spiritual leader Wovoka, who happened to be the son of one of Woziwob’s disciples. His dance also spread, from Nevada, to California, Oklahoma, Texas, and Canada. And there was something common about this shared human experience.

The ghost dance movement ended inevitably with the Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota.

As I read the history of this time of dance and expectations, I heard echoes of the “natural order of things” approach to technological change — that we judge technologies as right or wrong depending on our age at encountering them. But the ghost dance itself was supposed to do something a bit different. It was to bring about Wovoka’s vision of a return to the past — a time when things were better.

As was said, years after the ghost dances:

“Eighty years ago our people danced the Ghost Dance, singing and dancing until they dropped from exhaustion, swooning, fainting, seeing visions. They danced in this way to bring back their dead, to bring back the buffalo. A prophet had told them that through the power of the Ghost Dance the earth would roll up like a carpet, with all the white man’s works — the fences and the mining towns with their whorehouses, the factories and the farms with their stinking, unnatural animals, the railroads and the telegraph poles, the whole works. And underneath this rolled-up white man’s world we would find again the flowering prairies, un-spoiled, with its herds of buffalo and antelope, its clouds of birds, belonging to everyone, enjoyed by all.

“I guess it was not time then for this to happen, but it is coming back. I feel it warming my bones. Not the old Ghost Dance, not the rolling-up — but a new-old spirit, not only among Indians but among whites and blacks, too, especially among young people.”

— from Lame Deer, Seeker Of Visions, p 124

Ghost-Dance Religion author Mooney also notes other dancing and flagellant “epidemics” which emerged in Europe and the United States, including:

- The dancing epidemic of Saint John, which broke out in Germany, the Netherlands, and France in the 1300s and 1400s.

- The Flagellant movement, which erupted in Italy, France, Germany, Austria, Poland, Denmark, and England in the 1200s and 1300s.

- The Quakers, who early in their history, were known for violently shaking.

- The “Jumpers,” a group that started in 1740 in Wales, whose actions Mooney noted as most similar to the ghost dancers. They would repeatedly sing songs while jumping for hours.

- The Shakers. You get the idea from the name.

- And even the Methodists.

There is something internally human about this approach to change.

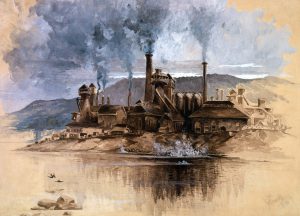

Guilds

I was curious about other situations when the world moved too fast and changed too much. What other tactics did people take? Affected groups try to sway the course of history in a few ways. But as Victor Hugo wrote: “One can resist the invasion of armies; one cannot resist the invasion of ideas.”

The invasion of ideas happened to the late 1800s iron industry with the new Bessemer steel production process. As industrialist Abram Hewitt noted:

“I look upon the invention of Mr. Bessemer as almost the greatest invention of the ages. I do not mean measured by its chemical or mechanical attributes. I mean by virtue of its great results upon the structure of society and government. It is the enemy of privilege. It is the great destroyed of monopoly. It will be the great equalizer of wealth. … Those who have studied its effects on transportation, the cheapening of food, the lowering of rents, the obliteration of aristocratic privilege .. will readily comprehend what I mean by calling attention to this view of the subject.”

The Bessemer process dramatically improved the earlier focus on the production of iron and enabled steel products to be made faster and cheaper. The finished results were harder and more durable. What’s not to like?

It depends on who you asked.

In Men, Machines, and Modern Times, Elting E. Morison described the reaction of many in the Pennsylvania iron industry this way:

“By hard work and infinite pains, they had reached a position of eminence in an ageless guildlike craft and in the community. Now they were suddenly confronted not by a new way to make iron, but by a new way to make something that would replace iron. Would not this new thing destroy the competitive advantage, so hardly won, by forcing every man to start over again in the same degree of innocence and from the same level? Would it not, by replacement of an old reagent, iron, with the new element of steel, replace also the customs, habits, procedures, and hierarchical arrangement upon which the security of life in the iron trade depended? The [Bessemer] converter, in this context, looks less like a tool of commerce and more like some catapult leveled against a walled town.”

The Bessemer steel process was relatively new. And up until that time, industrialists considered American iron inferior to what was produced in Europe. In fact, in England, the lowest grade railway rails were casually called “American rails.” But when American producers eventually embraced the new Bessemer process, they surpassed the other rail producers from Europe.

Those iron guilds just slowed down an inevitable process. Once invented, higher quality and cheaper steel was going to happen, whether it was with the guilds or without them.

But then who adopted the new technology? Morison says they came from outside the iron guilds:

“These were the innovators, the men without heavy commitments to the system of attitudes and prejudice built up in the iron trade…. They could weigh the merits of Bessemer steel not by trying to decide what it would do to them in the iron trade but what problems it would solve for them in their railroad interests.”

Generative AI

Guilds are sustainable when applied to products that don’t change much with technology. For example, food products where consistency and even the history and process itself is part of our enjoyment.

Ghost shirts work best when applied to cultural and religious aspects, which exist outside of objectivity and where faith is a requirement. For example, the beliefs related to individual and community purpose and meaning.

On the one side, we have fear and protective behavior that is guild-like. In that case we try to prevent the change from impacting us.

On the other side, we have a yearning for the past that is religious. In that case we reject the change.

But what about a pause?

A pause is neither of the above.

A pause admits that the change has come, but asks for a time out while everyone thinks a bit more and puts new precautions in place. On this blog, I’ve often asked not for a pause, but consideration of the precautions and trade-offs. For example, on this blog you’ve seen me argue against certain types of top-down change, including systemic risk from autonomous vehicles, universal basic income, species introductions, and more.

I’ve also argued that some awful changes, such as those in Xinjiang, with overbearing surveillance, and even robot soldiers, seem like they are inevitable.

But what if inevitability is just acceptance? What if it’s a choice? In Narrative Capture, I wrote about the Myth of the Inevitable. “When people believe something is inevitable, they won’t bother to fight it.”

How should we look at generative AI? If indeed we are at a point of inevitability, as I believe we are, slowing down only affects those who agree to slow down. The worst actors in such a situation would simply use that slowdown to continue to make progress and eventually even potentially get ahead. I know the authors of the letter believe otherwise, but I would like to know how we could ensure the pause is respected everywhere. Or rather than a “pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4,” what about no pause in the training, but a pause in deploying new AI systems instead?

We don’t know what will happen as changes in workforce, education, lifestyle, and meaning work their way through humanity. With a pause, we might delay the imagined benefits that generative AI could bring. As with unexpected impacts during COVID we will see things that might look worse than they actually are and only be temporary until finding a new equilibrium. Or, if that historical bubble did really pop, new equilibria might be short-lived.

From the “pause” letter:

“Contemporary AI systems are now becoming human-competitive at general tasks, and we must ask ourselves: Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? Should we automate away all the jobs, including the fulfilling ones? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us? Should we risk loss of control of our civilization? Such decisions must not be delegated to unelected tech leaders. Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable. This confidence must be well justified and increase with the magnitude of a system’s potential effects. “

I have often thought that my choice of domain name where I write these posts sometimes leads me to think of the downside of systems change. It’s easy to say “stay optimistic,” I suppose. But why is it staying pessimistic any better?

I’m neutral or even against a pause for generative AI, for the reasons above.

History is coming back. The train is leaving the station and you’re already on it.