When a new topic overwhelms — as with coronavirus — it’s easy to take in a lot of noisy information. Information that isn’t helpful, accurate, or clear. With that in mind, and especially for those of you physically isolated in response to COVID-19, I present this (long) quote about the Dark Ages of Europe.

“Whatever reproach may, at a later period, have been justly thrown on the indolence and luxury of religious orders, it was surely good that, in an age of ignorance and violence, there should be quiet cloisters and gardens, in which the arts of peace could be safely cultivated, in which gentle and contemplative natures find an asylum, in which one brother could employ himself in transcribing the Aeneid of Virgil, and another in meditating the Analytics of Aristotle, in which who had a genius for art might illuminate a martyrology or carve a crucifix, and in which he who had a turn for natural philosophy might make experiments on properties of plants and minerals. Had not such retreats been scattered here and there, among the huts of a miserable peasantry, and the castles of a ferocious aristocracy, European society would have consisted merely of beasts of burden and beasts of prey. The Church has many times been compared by divines to the ark of which we read in the Book of Genesis: but never was the resemblance more perfect than during that evil when she alone rode, amidst darkness and tempest, on the deluge beneath which all the great works of power and wisdom lay entombed, bearing within that feeble germ from which a second and more glorious civilization was to spring.”

From The Complete Writings of Thomas Babington Macaulay, Volume 1, History of England, Chapter 1 (1848).

But there are different types of isolation we enforce or seek out today. Might there be additional types in the future? Should we think about encouraging some new types of beneficial isolation?

And who today, in a very different world, is of the miserable peasantry, the ferocious aristocracy, or in the cloisters? Has that changed because of this pandemic?

Isolation of the body

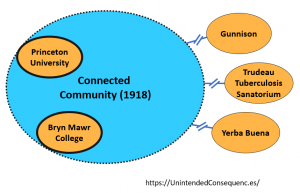

Let’s first look at a report on Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPI) during the 1918 flu that resulted in a small number of communities in the US escaping the brunt of that pandemic. (I’m referring to the unclassified report: “A Historical Assessment of Nonpharmaceutical Disease Containment Strategies Employed by Selected U.S. Communities During the Second Wave of the 1918-1920 Influenza Pandemic.”) The report was written by a unit of the Department of Defense in 2006 and highlights the communities of Yerba Buena Island, California; Gunnison, Colorado; Princeton University, New Jersey; Western Pennsylvania Institution for the Blind, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Trudeau Tuberculosis Sanatorium, Saranac Lake, New York; Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania; and Fletcher, Vermont.

From the list in the report:

- Yerba Buena, an island in San Francisco Bay, had no bridges connecting it in 1918. The location had no deaths and even no cases of flu during the 1918 pandemic. Apart from face masks worn by medical personnel, the island maintained a quarantine. When boats brought in supplies, crew members could not come closer than 20 feet to Yerba Buena personnel. Interestingly, Yerba Buena started its quarantine even before San Francisco identified its first case of the flu. For sanitation “the spigots of all drinking fountains were heated twice daily with the flame of a gas torch, and all telephone transmitters were disinfected.”

- Gunnison, Colorado implemented a “Cordon Sanitaire” for a few months (Oct. 31, 1918 – Jan. 20, 1919), including “[b]arricades erected on main highways with lanterns and warning signs.”

- And Trudeau Tuberculosis Sanatorium in upstate New York was naturally isolated with difficult access even in good weather.

That all makes sense. If no one enters with the disease, no one in the community will get it. Keeping barriers against the outside world took effort. But it’s more interesting to think about the connected locations from the list and what they were able to achieve while being located within larger towns.

- Princeton University, a part of the town of Princeton, New Jersey, forbade students to cross the street or enter off-campus buildings.

- Bryn Mawr College did not allow students who were “not on campus before protective sequestration enacted and those who left after it was in force… to return until Nov. 7, 1918.”

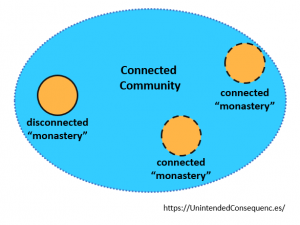

Those two locations enforced policy barriers to separate those inside from those outside. Since the physical barriers were weaker and the rest of the community was just outside the campus walls, the protected community depended more on its individuals following a policy. Something like this can work.

Isolation of the mind

Something else happened to those monks from Babington’s quote above. Those monasteries of the past weren’t isolated enough to protect against epidemics since the monks often went out to attend to the sick and then succumbed to the same disease themselves. Plus, there was only basic understanding of how diseases like the plague spread.

Today, if anything, there’s extreme practice of physical separation and understanding of the purpose for it. This heightened awareness makes some wonder whether the life of the recent past — with everyday physical gatherings in restaurants, schools, workplaces, and events — will ever return.

Some also find that there are other benefits to physical separation, even if the original purpose for social distancing was to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Those other benefits include no commutes, more family time, less pollution, and even fewer communicable diseases of other types.

While they may have only been partially isolated in the body, those monks were isolated in the mind by gaining the time to concern themselves with learning, ideas, contemplation.

It strikes me that part of the anxiety that some feel today is at least partly due to being physically isolated while not also being mentally isolated. Being able to hear about every new additional piece of news, the latest change in infection rates, case fatality, super-spreaders, treatments… The topic can overtake the thoughts.

(Here I am, unironically contributing to that, though I hope for the better.)

Today, an unintended consequence of greater global connectivity is the ability to spread disease, but it’s also the ability to spread disinformation, poor quality information, and too much information.

Though fueled by the Catholic church in Europe, many of the activities described in the Babington quote at top were not even directly religious. Transcribing Virgil. Meditating on Aristotle. Experimenting on plants and minerals…

The value was in the removal of some people from the rest of society and enabling them to work with less need to respond to social whims. The value was in “bearing within that feeble germ from which a second and more glorious civilization was to spring.”

How might people separate themselves in the future? I found someone who was thinking about that topic, before coronavirus, but with a allusion to my first quote above.

From Monasteries of the Future, a PhD thesis by Miles G. Bukiet.

“I propose here one type of positive institution, Monasteries of the Future, designed to train a new generation of elite monks, also called contemplative adepts. Monasteries of the Future will develop adepts by training virtues such as compassion, gratitude, and forgiveness. They will also teach foundational mental capacities like self-regulation, sustained, voluntary attention, emotional intelligence, and meta-cognitive awareness. By pushing the envelope in the contemplative field these adepts will probe the upper limits of human flourishing. The refining and sharing of such an education supports both the amelioration of suffering in all its various forms and the cultivation of an enduring eudaemonic well-being.”

Could we build something like this?

Consider

- Compared to the Dark Ages of Europe, there is a much higher amount of connection around the world today, even with lockdowns, of both the amount and speed of physical travel and the amount and speed of information travel.

- If you are not benefiting from the information you consume, slow down. The practice of a “digital sabbath” has its benefits. The digital sabbath is a day-long break from phones, internet, and other digital content. Go out in nature or read on paper.

- The argument behind thoughtful physical and mental separation is similar to the one for becoming an interplanetary species. Removing part of humanity to another planet improves the odds for survival in a truly catastrophic event where all life on earth is threatened.

- People have sometimes gone through the motions to build an appearance of disconnection. Hermits have even been recruited to live in, well, hermitages, placed on the grounds of a wealthy estate.