If you want to get in an argument when you travel (especially internationally), talk about history.

There isn’t a single, correct history. For multiple reasons, places around the world treat history differently than other subjects. The ways we deal with uncomfortable topics include suppressing, not learning, and biasing others.

Suppressing includes destroying information and punishing those who make it available. Not learning attempts to diminish specific information by not teaching it or discouraging people to learn it. Biasing keeps information available but tries to sway the interpretation of that information.

Some places manage their history closely. That choice tends to come from history too, as well as how risky change is.

I believe every place does this, but to different degrees. Some in direct ways, like the suppressing style. Others by making it difficult to learn something or biasing potential learners. Sometimes it’s not even intentional.

There’s a joke about this. A Chinese government employee from the state security agency comes to the US. At immigration, the border agent asks the purpose of his trip. “I came here to learn mind control so I can use it on the Chinese population,” says the man. “You’re in the wrong place. We don’t do that in the US.” says the border agent. “Yes! That’s it! That’s exactly what I want to learn how to do!” says the Chinese visitor, impressed by how US mind control is more advanced.

This year in Beijing, as at times in the past, activities in the weeks leading up to June 4th focused on something outside of China. This time it is the US trade dispute and international “bullying” that takes the focus nicely.

If you’re reading this, you’ve probably seen many articles over the last couple weeks about the 30th anniversary of the June 4th massacre, an event whose timeline was set in motion by commemorations of a popular political figure’s death. I wasn’t there. So instead I want to write about something I was at. A very different funeral in Beijing.

A Different Funeral

Deng Xiaoping, China’s (unofficial) leader died in February 1997. I was in Beijing the week of his funeral.

Mass gatherings and their unpredictability were certainly in mind in 1997 during Deng’s funeral. The 1989 Tiananmen protests had started off as a remembrance of a popular political leader, Hu Yaobang, who died in April of that year. Things then took an unexpected turn. Gatherings to pay respects turned into something else.

A call for democracy emerged, with many university students forming the movement’s leaders. Some leaders, like Zhao Ziyang, supported the students’ critiques but lost influence in the end to hardliners.

You know how it ended. That was 1989. When I was in Beijing in 1997 there were a few things that made that time different.

I showed up on Tiananmen Square early in the morning to see the flag raising ceremony. There were probably another thousand people there. After the flag went up, we all walked to the west side of the square, which faced the Great Hall of the People. Everyone looked around to see what would happen next.

Nothing really. More people arrived on the square. Everyone seemed to be waiting for something.

Every once in a while there was a sudden rush of hundreds of people. When it looked like someone was doing something (which might include holding up a sign, carrying a bouquet of flowers, or climbing on the Monument to the People’s Heroes) people ran over to see. It was always nothing. Or, as you’ll see later, there was a process to remove “anything.” Along the way I saw police pull cameras from hands but didn’t yet notice anything more than that.

I walked back to the north side of the square close to Chang’an Avenue. That’s when I was almost run over by a man pulling a walkie-talkie out of his heavy coat and shouting directions. The “anything” was an old man wearing the old stuffed cotton Chinese military uniform who had pulled out a long white scarf (a sign of mourning). Maybe he was a Long Marcher, I’ll never know. Within seconds, a circle of police surrounded the old veteran, facing outward. I kept standing nearby. In less than a minute a white van pulled up, the man was bundled inside, and it drove off. Anyone close by but facing the other direction never would have seen it.

Less than a minute later, a man approached me. He spoke perfect English (something that was rare in my Beijing experience in 1997). He had a long list of questions for me, including where I was staying, my home address, and more. In a few minutes he was gone too.

A smooth process to remove anything problematic was already practiced and in place.

When I noticed white vans pull through the crowd later during the day I knew what had happened. Suppress “anything” before it can turn into “something.”

I moved back toward the Great Hall of the People. At this point the square was pretty full.

At one point in the morning, a long line of police formed. All down the west side of Tiananmen Square (about half a mile long) they formed a line, locked arms, and started to walk east, at times pushing people who walked too slowly (including me). The entire crowd walked east with them until everyone was in front of the National Museum on the east side of the square.

When the square was clear, a long line of black Hongqi cars and buses drove in. Out filed the funeral attendees, who walked into the Great Hall of the People.

The thousands on the square stayed. I was “interviewed” by two reporters from People’s Daily. I met another American and two Mongolian students and we went to lunch. Big screens played scenes from the funeral and Jiang Zemin’s tearful memorial. (“Jiang has to cry,” said a friend of mine before the funeral.)

I went back at night. The square was pretty empty. Leaving to find a place to eat I realized that the official period of mourning meant that restaurants and bars were closed in the evening. Beijing had much less nightlife in 1997 but the mourning period was noticeably quiet.

Nothing was open. I was hungry and thoroughly cold from being outside all day. I kept walking until I finally saw a restaurant with all its lights on, packed with people.

“Heyyyy!!!!!!” yelled everyone in the restaurant.

I had just walked into a place packed with off duty policemen. Of course. No other restaurant would dare remain open after curfew hours.

I took the only open table and was quickly joined by the man I’ll just call the chief. He showed me his badge. What followed was a quick conflict of historical differences with humanity mixed in, as my notes and memory have kept it. Every military mention was made inches in front of my face. And everyone was drunk.

“Hey American, what are you doing here?!” said the chief, sitting down right next to me.

“I’m trying to get something to eat.”

“Don’t you know this is a period of mourning? You can’t be out this late!”

“I saw that this place was open so I came in.”

“You should go back to your hotel. Remember, China defeated the US in war! What are you ordering?”

“What did you…? Uh, dumplings…. Or…”

“Get the lamb. China defeated the US in your imperialist war with Korea!”

“Are you talking about the Yalu River… I don’t think that defeat is the way to…”

“Hey waiter, the American’s ready to order!”

All throughout this time a few nicely dressed women took turns cuddling up to the policemen.

“Hey American,” said the chief again. “Do you know why she doesn’t like you?”

“Uh…”

“Because we defeated you in war!”

To one country, it’s a defeat. To another, it’s a footnote. It wasn’t that the US suppressed history of the Korean War and China’s involvement. It’s that it’s a small point in one of many wars. It’s not taught, it’s not learned. But to a Chinese audience, that point is a mark of power and pride. I was intrigued to see that movies about the Korean War are pulled out again as the US – China trade war develops.

The Chinese style is heavier on suppressing and biasing while the American style is heavier on not learning and biasing.

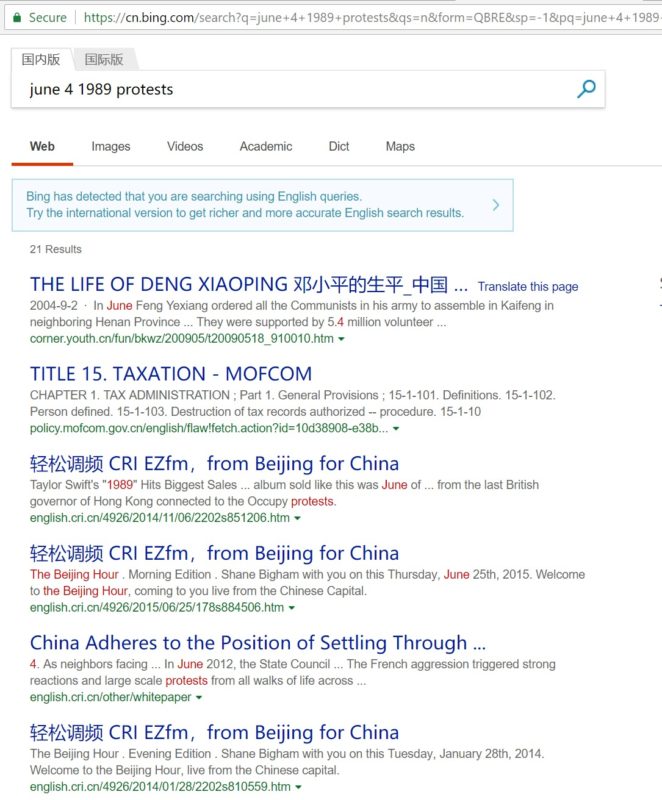

For example, an online search on June 4th, 1989 gives these innocuous results in China.

There isn’t broad awareness among young people in China of the June 4th event, something which means that censors must be trained to know how to censor messages about it. Suppression can work depending on how much effort a group puts into it.

Something comparable in the US would just have to compete with many other issues for attention. Or it would have its own group that demands to teach more about it.

Where does suppressing, not learning, and biasing produce after years of practice? It leaves different peoples with different views that conflict. For the riskier countries — the ones where more attention is on what their history is — is there eventually a point of system collapse?

Things with the policemen went on like that during the whole meal. It was really all bravado and in good fun. Many beers were brought over to share. I drank many toasts with the policemen, who were all pretty mild mannered compared to the chief. I actually drove with two of them to a karaoke bar which was closed because of the mourning period. They dropped me off at my hotel instead.

I wonder where they are now.

I thought back to the first time I went to China — in 1990. A trip to Beijing and Xi’an which served as a baseline to my other China travel given how fast things changed. It was also the only time I was in China without being able to speak at least one of the local languages. On that first trip, a member of the tour asked the guide, who was from Beijing, what happened on the square in June of the previous year. Everyone else looked at him in shock but the guide answered in the best way possible:

“I don’t know. I wasn’t there.”

Consider

- A top-down suppression approach can let risk grow.

- The suppression approach means that you must remain suspicious of coincidences. Like when the stock index fell by 64.89 points on June 4, 2012.

- A large security agency or new tech must be developed. This has other impact elsewhere in the country.