Let’s come back, more directly, to a theme in my writing — what happens when something small becomes a tipping point for change. When the seemingly innocuous becomes unpredictable.

If you’ve only casually followed the Hong Kong protests and reaction from the Chinese mainland and overseas Chinese communities, you might wonder about the importance and meaning of the covered eye. Specifically, the right eye.

Hong Kong protesters found one of their many symbols (and there are many) when police shot and injured the right eye of a protesting woman in August. The injured eye is a more powerful symbol than even that of the man police shot on October 1 (Chinese National Day) in the chest (that is, the heart).

But since the now famous protester’s eye injury we’ve seen company ad campaign apologies and even an individual arrest all because of missing eyes.

But the eye I was reminded of was none of these. It was a different eye — also a right eye and in China — that over 40 years ago had results reminiscent to those eyes of today.

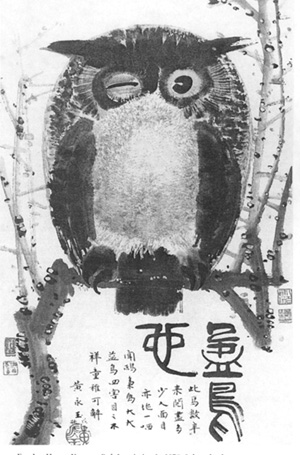

If you are a student of Chinese Cultural Revolution artwork, you might recognize this painting of an owl by Huang Yongyu.

Huang served three and a half years in a labor camp for it.

The painting was interpreted as a “portrayal of public officials turning a blind eye to wrong doings.” It’s not clear if he meant it as such.

Huang’s owl was one of many works of art gathered for a “black painting” (meaning counter-revolutionary) exhibition and criticism meeting in the 1970s. In some cases, officials had to scrounge around to find more “black painters” to have enough art to criticize. If you read some of the art descriptions, it seems like at least some of the artists were just unlucky rather than counter-revolutionary.

And while I haven’t seen anyone publicly connect Huang’s winking owl with the protests of today, I imagine people with longer memories think about it.

Next in chronology we have of course the event from this summer in Hong Kong. A woman attending a protest was shot in her right eye. Covering one’s right eye soon became a symbol.

And as a good symbol, it is impossible to ignore (you can’t look away from someone’s eyes and still talk). As a good symbol it also brings the eye-patch wearers themselves into some discomfort.

The eye symbol became even better known when a foreign company felt pressure to remove and apologize for an old ad that predated the Hong Kong protests, but which happened to include a covered right eye.

Here’s a Tiffany ad (since removed) that pre-dates the protests.

And here’s another Tiffany ad, also removed following complaints to the company for stirring up social disorder.

And to compare, here’s another picture of Sun Feifei (the same model in the second Tiffany ad) covering her right eye in another photo shoot, also months before the protests in Hong Kong. And actually shown on a government-run website, even today.

So eye covering can look like a matter of intent. The china.org.cn right eye picture can obviously have no connection to the Hong Kong protests. But a foreign company is different, even with ads shot months before the covered eye became a protest symbol.

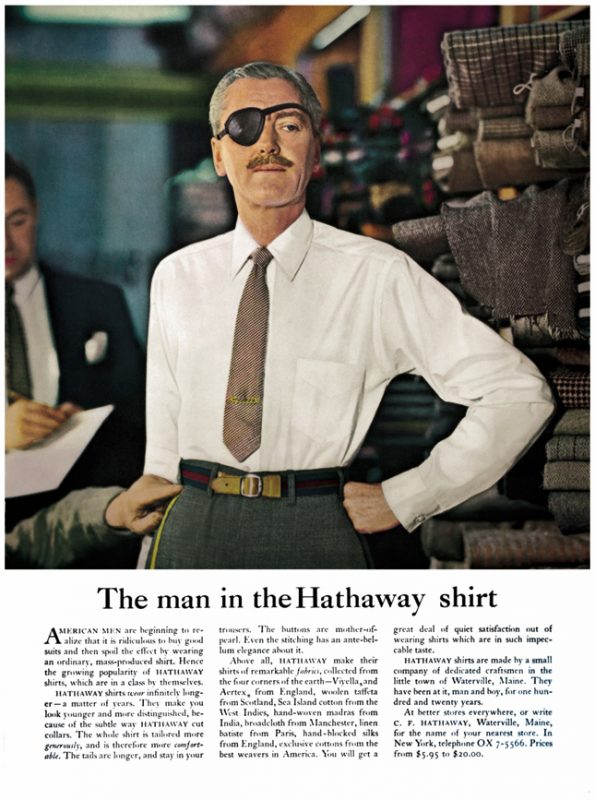

Of course, the covered eye — again, the right eye — has been used famously before in an ad campaign: “The Man in the Hathaway Shirt.”

No political meaning. Just an Ogilvy ad with the eyepatch used as a gimmick.

But there’s more again.

A Houston Rockets fan in China (the same team whose manager posted a “Stand with Hong Kong” tweet) was much too cynical on the ability of his government to track him down.

The first line (after the hashtag) says: “I live and die with my team.” The second line: “Come and catch me.”

They caught him, just a few hours later. And it appears he covered an eye to make facial identification more difficult. But again, what if he hadn’t covered his eye?

The apology from Tiffany strikes an international audience as the exportation of anti-protester values. The above picture of the NBA fan chained in a “tiger chair” strikes an international audience as not the future they want for themselves. Has the visual symbol of the eye — uncontrollable once the injury and advertisements happened — helped spread this message further?

Wearing of Masks

Should protesters anywhere be allowed to wear masks? While a number of US states already had mask bans in public spaces, general public opinion seemed even more in support of the bans after a number of mask wearing Antifa members beat up a reporter in Portland earlier this year. The argument against masks was that covering one’s face minimize the feeling of social disapproval and led to worse behavior.

The US has at times overturned mask bans, famously after the Iranian Revolution as a way to protect Iranian protesters in California. But those masked were protesting a government from which they had fled to the US. It’s a different story when the protesters are domestic.

But a different explanation emerged in the Hong Kong protests now that we have identity at scale. Protesters had already taken cautions to avoid identification by using single-use MTR (metro) transit cards and paying in cash. But faces could be identified at scale either live or in the near future by capturing records of protest attendance, assessing behavior, and following up with repercussions.

Hong Kong protesters also try to take down eyes on the crowd in the form of smart lampposts. There are a number of videos of them dismantling these lampposts out of fear of surveillance.

For me it’s interesting to reflect on the news from Hong Kong because Hong Kong is a place I have visited over almost 30 years. During that time, I also lived there for around six years. Five of the visits and about one year of the living there was pre-Handover. In the time leading up to 1997, I observed (can’t really say I demonstrated) in a few events. These fell into a few types:

- Marches, often along Queen’s Road, in crowds in the tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands.

- Sit-down demonstrations outside of the New China News Agency (the NCNA was the de facto Chinese embassy pre-Handover).

- June 4th remembrances in Victoria Park (including the last pre-Handover one), often culminating in the crowd holding lit candles. Cui Jian’s Nothing To My Name would always be played (a song popular at 1989 Tiananmen).

No one wore a mask, because there wasn’t any need to do so. The protest leaders were already known. The crowd was safe in numbers. I never heard anyone fear identification, even post-Handover.

If you contrast the protesters of back then with those of the last six months, they are unrecognizable.

That protesters hide their faces and cut down smart lampposts makes sense. Like the eyes in the advertisements above, the lampposts may not have any intent to use facial recognition to identify protesters, but there is no trust. Anything can look suspicious. If the capability is there to help your adversary, then you assume they use it. Especially if there are examples of mass surveillance already in place, for example in the Chinese province of Xinjiang.

Consider

- Identity at scale can weaken trust.

- Visual symbols can spread a message.

- Huang Yongyu’s owl paintings now sell at auction.