One of the themes of these posts is that we unintended consequences of a change come from the way it scales.

It is also superficially easier to judge events as at risk of unintended consequences (easier, not more accurate) when there is an image — a snapshot — that represents risk.

So what are causes of difficulty when we make judgments? I’ll go into some examples.

After two back-to-back mass shootings in the US, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson tweeted something seemingly logical yet awful (shown later in post). Interestingly, people took offense and attacked him for the apparent logic (he later apologized). His offense: insensitively calling out and comparing the magnitude of different causes of death.

But the problem with Tyson’s tweet wasn’t that at all.

3rd of May, 4th of June, 5th of July

A snapshot will often be selected to represent a complex event. This is Francisco Goya’s painting, The 3rd of May 1808.

This painting is from a time before literal snapshots. And if you know this painting, you likely know it for the work of art more than the history it represents. The art historians beat the historians on this one.

Goya’s painting is an image of weakness (the French army shooting Spaniards) as eventual strength (Spain was the victor).

Goya only painted The 3rd of May after the end of Spain’s war with France. The conclusion was known. People had moved on. But the painting created an enduring memory as if to say: “See those people over there? Remember what they did to you and how things might have turned out.”

The second date in my list is different. There (June 4th), the defining snapshot is of a man, identity unknown, standing in front of a tank. Different from Goya’s painting, in June 4th it’s the same people (in a national or ethnic sense) at odds in the image, while still capturing an image of weakness and strength. And the image remains so powerful that it cannot be shown in some places even 30 years later. That date also represents the closure of a turning point. That was the point at which the student protests in Beijing and around China, seemingly scalable to the point of system change, were actually squashed.

Then there is the third date (July 5). That was the start of a protest, then a series of attacks (first by Uyghurs, then by Han Chinese) in Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang, China in 2009. The start of the path is usually interpreted as the deaths of two Uyghurs in Guang Dong province a couple weeks before. This example is a mix of the two situations above — the people fighting are from the same country, but of different ethnicities. The July 5th events are often linked to the eventual (perhaps inevitable) mass internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang in 2018.

Not enough time has passed for the conclusion in Xinjiang to seem clear though it is probably already irreversible for the Uyghurs. July 5th was a potentially scalable event and therefore attracted great attention.

And for that there is no one image. There can’t be.

Brits, Spaniards, Californians

When people lack or have a different fear of the scalable than ourselves, we get upset.

During the September 11th attacks I was in London. The local reaction was overwhelmingly supportive to the US. When people learned I was from New York it tended to startle them, with careful follow-up questions about it, if I knew anyone affected, and more.

If those towers didn’t fall (the snapshot) but the same number of people died, I imagine a milder reaction.

Shortly afterward I went to Spain. The common reaction there: “Well, we’ve had terrorism in this country for 30 years with the Basque separatists. You had one event. How many have we lost in that time?” No one liked the answer (almost 3,000 in a day in the US versus 800 over 30 years in Spain). This is the problem of entering a competition for worst results.

But the most surprising reaction was a couple days after the attacks. I visited the vigil at the US embassy, then walked into a pub and struck up a conversation with the bloke next to me. He was from California.

“Tough times,” I said as we took a drink.

“What do you mean?”

“Uh, the attacks…”

“Oh, that? That stuff won’t be too bad. There are bigger problems.”

I downed my pint and left.

Neil’s Tweet

After two back-to-back mass shootings in the US, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson tweeted the following:

In the past 48hrs, the USA horrifically lost 34 people to mass shootings.

On average, across any 48hrs, we also lose…

500 to Medical errors

300 to the Flu

250 to Suicide

200 to Car Accidents

40 to Homicide via HandgunOften our emotions respond more to spectacle than to data.

— Neil deGrasse Tyson (@neiltyson) August 4, 2019

He faced criticism, to say the least. But why?

The obvious answer is that the tweet, right after a tragic event, seemed insensitive, rude, out of touch. Many of his online critics even noted their own refusal to measure the 34 deaths in a logical way. Their claim was that he was logical, but wrong to write what he did.

I disagree.

Yes, his tweet was in bad form. But the larger problem with the tweet was that Tyson ignored the ability of each cause of death to spiral out of control.

In our current systems, medical errors, flu, suicide, and car accidents don’t dramatically change in scale. They also require large numbers of people to come up with those large numbers of deaths. To dramatically increase the deaths from those causes would require something big about the system itself to change. For example:

- Scaling medical errors requires procedural changes, electronic medical records systems bugs, or sudden reduction in staff to change the quoted number.

- Scaling flu requires either the sudden appearance of a superflu (like the 1918 Spanish Flu or 1968 Hong Kong flu) or a sudden reduction in the care for flu patients.

- Scaling suicide requires sudden reduction of mental health services or the introduction of new scalable social pressures.

- Scaling car accidents requires either difficult changes to safety regulations, or autonomous vehicles deployed widely, which are at risk of scalable hacks and bugs.

In other words, without system changes, the above causes of death are difficult to increase rapidly. That’s why Tyson even knew those numbers.

But in the case of homicide via handgun, there isn’t a steady state for the deaths. Changes in gun laws allowing easier purchase of weapons, less mental health care, access to weapons that can kill more people faster all combine in a situation that can suddenly burst upward from few individual actors. Yes, that creates a “spectacle.”

The death of a loved one impacts their family and friends. But unlike the first four causes of death, homicide via handgun creates ripple effects far beyond. Just the sound of a motorcycle backfiring was enough to cause panic in New York’s Times Square. Just the mental toll of losing a friend in a mass shooting is enough to believe another one is happening right outside a classroom (as a USC professor believed in 2017, causing a campus-wide panic).

No stampedes happen because of medical errors.

Pro-Hong Kong and Pro-China Protesters

In the recent Hong Kong protests, you can look at the international mainland Chinese university student or recent immigrant as just acting out a script, but that’s not it. You can critique the irony of protesting outside of China in a way that wouldn’t be tolerated for other issues while in China. But that’s not it either.

If the Hong Kong protests are interpreted as a way to split off a piece of China (a mischaracterization), then if successful, they are a dangerous precedent that then impacts stability in Xinjiang, Tibet, contested islands, and elsewhere. It’s potentially scalable. In that framing, a strong reaction is logical. You, as an international reader might disagree with the Chinese perspective, but given that perspective, the reaction makes sense.

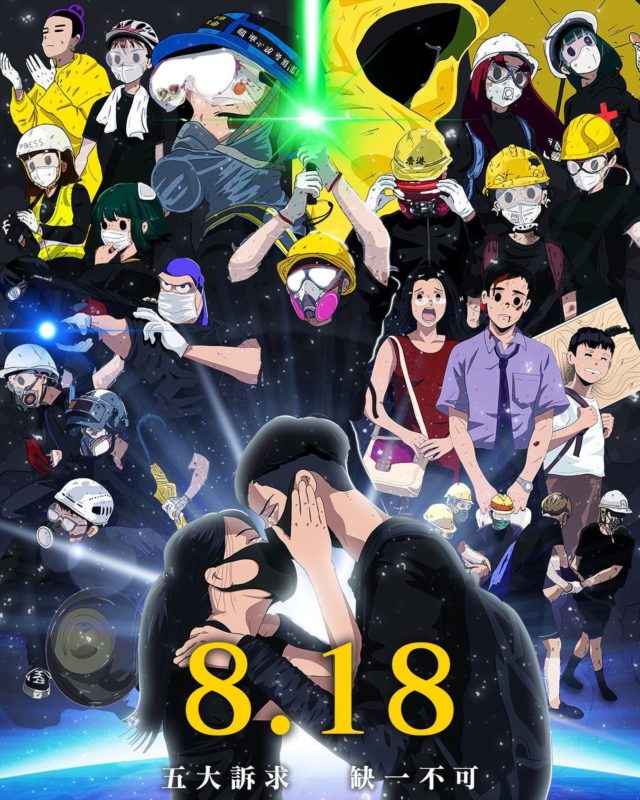

However, the Hong Kong protesters have the stronger selection of snapshots (and probably always will in this situation). Here’s just one example.

A bit complicated, but the call-back to individuals and techniques used in the protests, plus the Star Wars style look is relatable and just amazing.

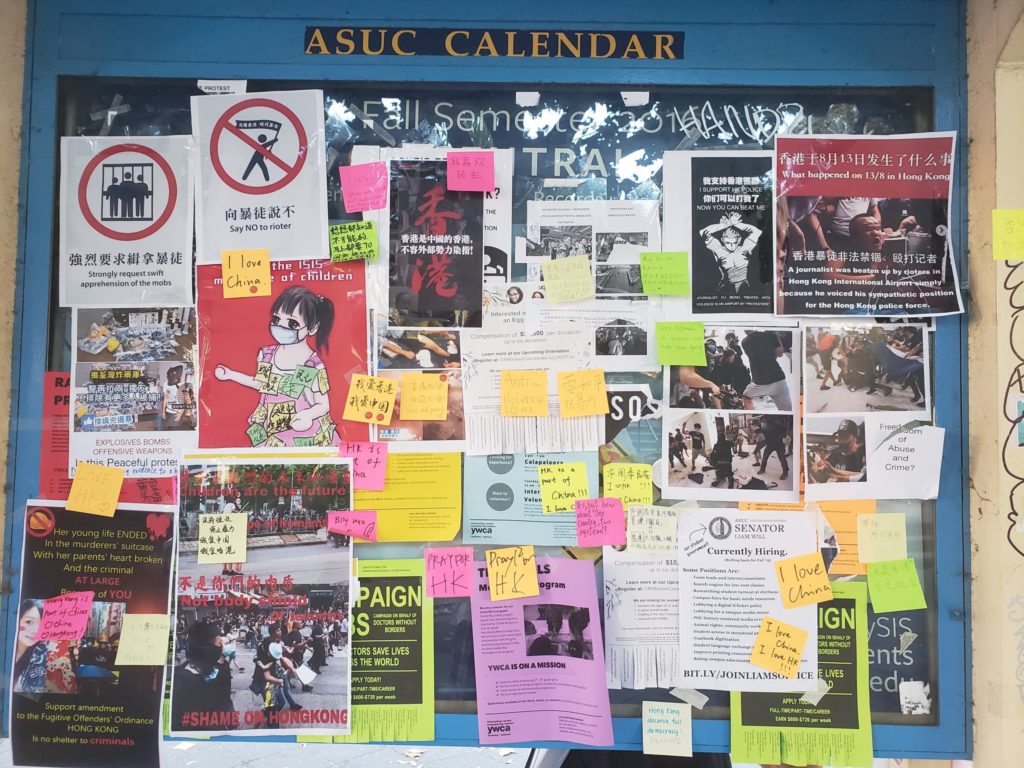

On the China side, the snapshots are weaker and are reliant on greater numbers of protesters outside of Hong Kong, in addition to greater numbers of flyers put up (at least at this point) on international university campuses. The image of large crowds berating Hong Kong protesters will not change anyone’s opinion, though they might intimidate. These images are not for an international audience, but for a domestic Chinese audience.

While the second snapshot is more organic (more people made individual contributions), the first snapshot is more scalable. The stylized movie poster image is more memorable and sharable. People might remember some elements of it in say… 30 years.

Consider

- Evaluate the risk of an event in terms of its ability to scale beyond initial conditions.

- Evaluate the reaction of others in terms of their belief (whether direct or indirect) that the event you support is scalable.

- There’s overlap in the way I’m writing about scaling, but more top-down hierarchies like the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) fear emergence (what starts out as one thing and becomes something very different).

- Creating and controlling the images people remember is a way to guide and manage second-level effects.