“As soon as a coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs.” Or, in German and with a similar rhyme, “Wenn die Münze im Kästlein klingt, die Seele in den Himmel springt.”

A friar named Johann Tetzel may or may not have said those words in the early 1500s, but the money he raised by selling indulgences helped rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica.

But what is an indulgence?

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

“An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven, which the faithful Christian who is duly disposed gains under certain prescribed conditions through the action of the Church which, as the minister of redemption, dispenses and applies with authority the treasury of the satisfactions of Christ and the saints.”

In some situations, even after forgiveness, there is still a punishment. An indulgence removes that punishment. For example, according to an article on the The Historical Origin of Indulgences, indulgences were granted for:

“Singing the Salve Regina, reciting the Angelus, praying for the dead in cemeteries, visiting particular sacred images or relics, listening to a sermon, accompanying the Blessed Sacrament when it was brought to the sick…. so many occasions were enriched with indulgences, and the piety of the faithful continued to ask for more….

“Indulgences were attached to many works that were not only good but also served the common good, both religious and civil. Many churches were built or restored — at least in part — with the revenue from indulgences; this also explains the impressive architectural and artistic activity of the Middle Ages. Moreover, hospitals, leprosariums, charitable institutions and schools were built with support from the receipts of special indulgences….”

But Tetzel’s corrupting innovation was to turn indulgences, something associated with good works, including almsgiving, into transactions. This meant that indulgences turned into commercial matters that one could buy.

Interestingly, the attraction to buying indulgences came from a misunderstanding (fortunate for the sellers) that simply buying an indulgence lowered one’s potential time in Purgatory. The Catholic Revival after the Protestant Reformation ended this financial corruption.

Enter the Secular Indulgence

In my first post here, in 2018, I predicted voice AI would make phone scams, such as the “grandma scam,” easier to perpetrate at scale. Much of that prediction came true.

But people who fall for those scams are directed outward. They are trying to save a loved one in trouble rather than themselves. They don’t know what the loved one did, or if they are really in trouble. It is the scammer’s threats that pressure their victims to transfer money.

It’s a different story when the target of the scam is trying to save themself.

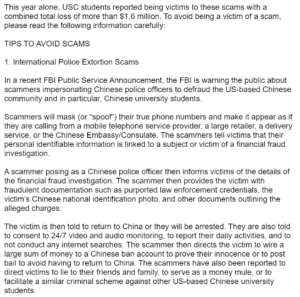

At 6,035 individuals, Chinese nationals are the largest group of international students at the University of Southern California, or over 12% of the total student body.

So it’s a shame when you receive a letter like this.

The historical corrupted religious indulgence appealed to belief, so outside of the religion the corruption had no effect.

This Chinese police student scam works and fails in a related way. If scammers call an American student by mistake, there would be no impact.

But to the Chinese nationals, the scam is believable. It’s known that there are secret Chinese police stations scattered around the US, an innovation in policing Chinese citizens living abroad. Until these police stations are identified and publicly eradicated, their existence opens up Chinese nationals to fake police scams.

If you live outside of your home country, what laws do you follow? Do you follow the laws of the country in which you currently live, as is the norm? Or, expecting extraterritorial jurisdiction, do you continue to follow the laws of the country you left? Are you potentially guilty of something because of where you are from? Or are you potentially innocent because of where you did it?

The Chinese student scam seems plausible to the victim because of the expectation of extraterritorial jurisdiction. So the victim purchases a secular indulgence to avoid the risk of punishment when they return to China, or alternately, they purchase the indulgence to keep their family out of trouble. The scammers benefit from the uncertainty of these situations.

(In this case I’m assuming that most of the $1.6M was centered on the Chinese students mentioned. Carrying that forward to the 290,000 Chinese international students in the US, sums to $77M total.)

Integrating the Indulgence

The American secular indulgence deals with legal uncertainty of a different type. Did you pay the proper amount of income tax? Even experts don’t really know.

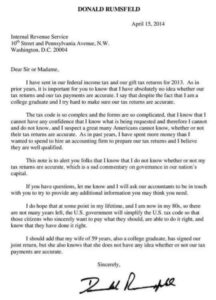

Here is one of Donald Rumsfeld’s famous IRS letters.

The complicated US tax code leads Americans to spend 6.5 billion hours and $104 billion annually to prepare and return their tax returns. (OK, maybe this is on the high end, but directionally it’s telling.)

Part of the issue is that the developed income tax filing industry supports making tax filings harder for Americans.

It’s hard enough that some well-known tax evaders (whether intentional or mistaken) include Martha Stewart, Willie Nelson, Nicolas Cage, Wesley Snipes, and more.

Another reason may be… it’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

Income tax evasion is a way for governments to go after those they can’t catch in other ways.

Al Capone was convicted on five counts of tax evasion. Not his mafia activities, but tax evasion. He served 11 years in prison after the Supreme Court ruled that illegal income was also subject to income tax.

Even Trump was targeted with tax evasion (now forgotten) in the weeks before the 2020 election.

This secular indulgence seems like the least threatening of the examples here (compare Chinese prisons or damnation).

Can You Avoid the Secular Indulgence?

There are a few forms of indulgences, including these covered above:

Pay to avoid — Tetzel’s selling of (spiritual) indulgences relies on a misunderstanding.

Pay after you are “caught” — The Chinese student scam: pay to remove the unexpected guilt.

Pay to avoid an error — the IRS secular indulgence: pay experts to minimize the chance of guilt.

The secular indulgence depends on some preconditions.

- Payment to deliver innocence or freedom from punishment.

- A higher power that pronounces guilt or innocence. Governments (whether actual or scammed) rather than religious organizations.

- Unclear rules and the expectation of confusion. If the rules were clear, the individual would know whether they were innocent or guilty in advance.

- Expected harsh punishment when failing to pay the secular indulgence.

Therefore, the secular indulgence cannot easily be avoided.

The secular indulgence cannot easily be avoided because it leverages fear, confusion, and urgency, and manipulates individuals into paying for freedom from punishment.

The complexity of the US tax code, with its difficult to understand rules and exceptions, creates fertile ground for such secular indulgences. Few people feel confident they’ve understood and followed every rule. In the tax system, hiring an expert produces peace of mind that the taxpayer has done enough to satisfy the unseen authorities.

Similarly, in cases like the Chinese student scam, the secular indulgence exploits the fears of international students who find it plausible that they are under surveillance and are unsure of whether they violated a rule. Confusion reigns and it’s easy to feel compelled to pay.

These modern indulgences remind us of Tetzel’s 16th-century sales pitch. If government reach grows more extensive and laws overlap across borders, secular indulgences will continue to emerge.