Today I was reminded of the first post I ever wrote on this blog (Voice AI, Telecom, Scams, and Co-evolution), back in 2018. My first article was focused on second-order effects of emerging voice AI capabilities and projected a number of scams that the technology would enable.

While this tech also has many positives, I always try to get a fuller picture by looking at the system.

The world is full of trade offs. In the case of voice AI in the article, we have the ability to scale up scams that historically worked, but only in small does. The “hey grandma” scam was one example. As I wrote back then:

“An older scam that this tech will scale is what’s known as the “Hey, Grandma” scam, where a grandparent gets a call from a “grandchild” in distress. There are different flavors of this. For US grandparents the story is often that the grandchild got into legal trouble and needs money wired. In China and Taiwan, it’s often that the grandchild has been kidnapped and is being beaten up. Again, wire the money.”

It doesn’t matter that most don’t fall for the scam. In cases like these where you can take a process of theft that formerly needed a human thief to target people one by one, by automating the process, you can benefit from scale effects. That is, it doesn’t matter that only a tiny fraction of people fall for the scam as long as you can spread it around broadly enough and not use up all of your time doing it.

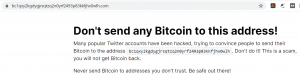

Today a different scam played out on Twitter. Multiple well-known accounts (Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Mike Bloomberg, Jeff Bezos, and more) were hacked. Their pinned tweets became versions of this message. (I blocked part of the address so I wouldn’t be distributing this even further.)

The messages on the hacked accounts were up for a couple hours — quite a while in online terms for such large accounts. Only Twitter really knows how many people saw the tweets, but it’s roughly:

the total number of followers of the accounts (perhaps close to 100 million) + the number of people Twitter showed the retweets (people retweeted out of both belief and irony) x the percent of people who happened to be on Twitter for those couple hours x the percent of people who believed the messages x the percent who had Bitcoin…

What’s more, these messages apparently resulted in around $60,000 of Bitcoin transferred to the scammer’s account, which was then transferred elsewhere.

Another way to think about this is that even by taking over all of those large follower accounts, the scam only managed to affect around 300 people and $60,000. There are much bigger scams that we never hear about. I can’t help but think that this scam in particular seemed like a bigger deal because the scammers took over what is in effect a public discourse channel that these large accounts use.

Like any large-scale sudden unexpected news, it led to a lot of contemplation. One of the most interesting critiques I saw was this one.

It’s a good question, why indeed is this the best that somebody could do. But we’re probably overthinking this. This seems to be a hit and run, not anything grander. But it has certainly made me (and I’m sure others) think about what exposure we have to Twitter and other user-generated content (UGC) networks.

Others came along to warn people away from the scam. While the scam propagated fast, it was also interesting to see just how fast users on the network helped prevent damage. Someone actually registered a domain name with the scammer’s address just to show this message.

In an older time, people wondered about broadcast signal intrusion — in other words, taking over the airwaves — to broadcast a diabolical message to a helpless population who only have access to three TV channels. Those villains, both real and fictional, did this to intimidate or brag, not to steal.

But back to the Twitter accounts hack. Rather than steal $60K, imagine if the scammers set their sights higher. Wouldn’t it be much better to try to persuade a large audience? Imagine doing this on election day.