It’s may be a bit overused, but I’m going to start this essay with a Kundera quote from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.

“In February 1948, the Communist leader Klement Gottwald stepped out on to the balcony of a Baroque palace in Prague to harangue hundreds of thousands of citizens massed in Old Town Square. That was the great turning point in the history of Bohemia. A fateful moment of the kind that occurs only once or twice a millennium.

“Gottwald was flanked by his comrades, with Clementis standing close by him. It was snowing and cold, and Gottwald was bareheaded. Bursting with solicitude, Clementis took off his fur hat and set it on Gottwald’s head.

“The propaganda section made hundreds of thousands of copies of the photograph taken on the balcony where Gottwald, in a fur hat and surrounded by his comrades, spoke to the people. On that balcony the history of Communist Bohemia began. Every child knew that photograph, from seeing it on posters and in schoolbooks and museums.

“Four years later, Clementis was charged with treason and hanged. The propaganda section immediately made him vanish from history, and of course, from all photographs. Ever since, Gottwald has been alone on that balcony. Where Clementis stood, there is only the bare palace wall. Nothing remains of Clementis but the fur hat on Gottwald’s head.”

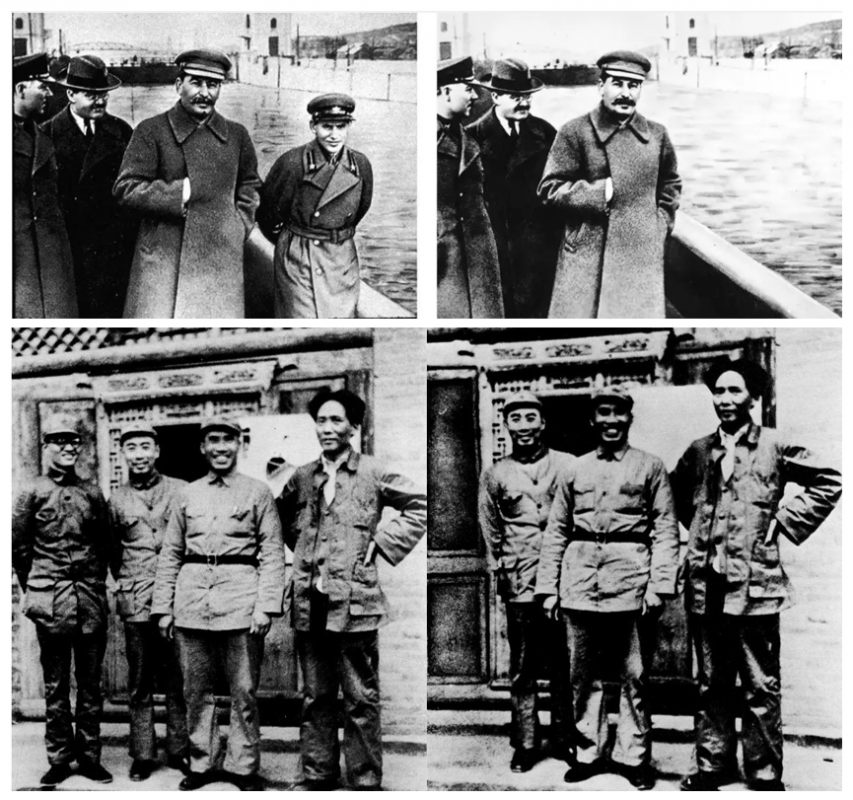

There are numerous examples of removing someone from history, mostly from national leaders who didn’t need subtlety in their actions.

Some of the most obvious examples come from authoritarians and apart from Gottwald, include Stalin’s historical removal of Leon Trotsky and Nikolai Yezhov, or Mao’s removal of Bo Gu. But how else do we remove people from history? Does the inability to ever truly erase something online change this?

Let’s look at ways we choose to eliminate history and when we do it.

The Future Isn’t What It Used To Be

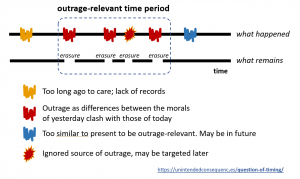

A difference between the examples above and practices of today comes down to a question of timing. Those previous purges of historical and photographic memory were done in the moment. Someone originally in favor started to overstep boundaries, challenged a leader, and was deemed unfit to represent a nation. They were then removed from history for safety of the status quo, as punishment, and because of their own actions as judged at the time.

In some Roman examples, this erasure also sometimes happened shortly after the death of the individual, for example when a Roman emperor died and the emperor that replaced him was an opponent settling a score.

It seems to be quite a different thing to do this decades or centuries after the fact. When that happens, new people, who not only never met the candidate of erasure, but people not even alive at the time of the individual’s actions now judge them. When these candidates are deemed unfit institutional representatives they are removed from the past or criticized with morals and laws of today.

Perhaps something like this.

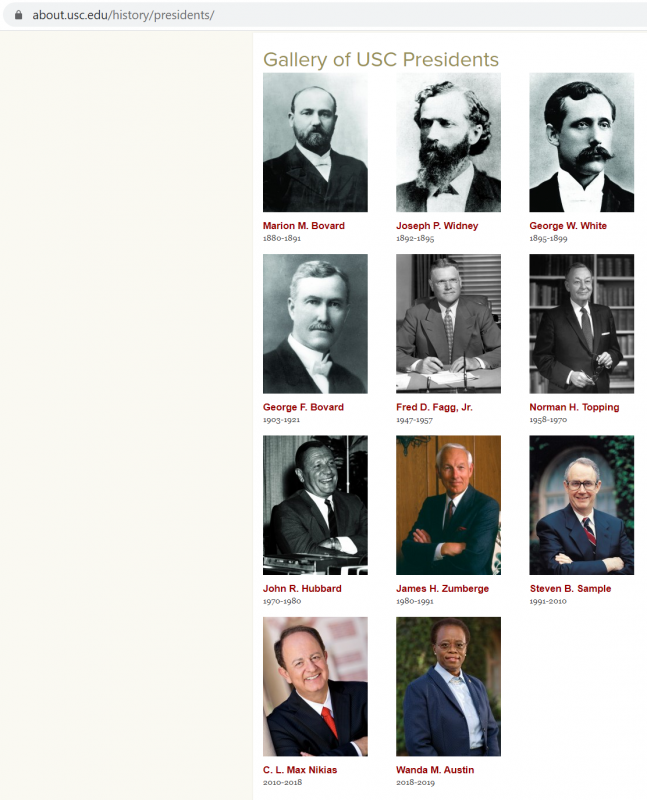

This idea came to mind when I recently reviewed the list of presidents from USC.

I thought the list seemed a bit short for a university that’s been around 140 years. Then I noticed the unspoken 25-year gap. The gap, from years 1922 to 1946, is where Rufus von KleinSmid previously was. (The other gap, from 1900 – 1902 is when USC actually had no president.)

Ironically for me, von KleinSmid Hall (now renamed generically as the Center for International and Public Affairs) was the first university building I taught in. After my office moved, I have for the last four years been based out of another location that does not bear his name, but which does have a plaque outside the entrance mentioning that he dedicated the building 100 years ago. I expect that if I ever return to campus I’ll find that plaque removed as well.

From USC on removing von KleinSmid’s name from a building:

“Students, faculty, staff, and the Nomenclature Policy Committee have pushed for this for years. He was the University’s fifth President, for 25 years. He expanded research, academic programs, and curriculum in international relations. But, he was also an active supporter of eugenics and his writings on the subject are at direct odds with USC’s multicultural community and our mission of diversity and inclusion.”

I have no stake in von KleinSmid and until recently didn’t realize that he was formerly a long-standing and popular university president or that he had conducted eugenics research. As with many universities, there are a lot of names on campus and I never thought of looking up his name before this time. So it was a bit of a surprise to learn about him.

I have no problem with changing names on university buildings. Von KleinSmid was born in 1875 and died in 1964. As Kundera said in another book, “let the old dead make way for the young dead.” But the removal from the list of presidents seems odd, unless it is possible to retroactively remove someone from office over 50 years after their death.

This debate will go on for a little time. In the case of the universities, renaming buildings may actually turn out to be a money-maker. It’s not often that a university has that opportunity. That’s also different from raising a naming gift for a new building. Being able to change the name of a university building comes without a cost for the development office to raise the funds from donors, as well as the time and expense of construction (often but not always completely funded by the donors).

The easiest way to rename in the moment is to replace a problematic name with something generic. It’s too soon to assign a donor name to a building (and it takes time to raise money). For example, Princeton’s newly named School of Public and International Affairs was the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs until recently. Five years ago the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill renamed Saunders Hall to Carolina Hall.

But the erasure from the historical list is interesting. I won’t be surprised if another USC president, say from a few years ago, will also eventually be removed from the list.

Page 2 Results

Even in the Roman era “damnatio memoriae” (“condemnation of memory”) pre-Internet past, it was difficult to truly erase someone formerly well-known. But truly erasing someone well-known required removals from public monuments and inscriptions. Tougher still if they were on a coin!

And Roman era damnatio memoriae rules had unintended second-order effects, but those could be managed, as I wrote in Destructive Collection.

Damnatio memoriae sought to:

“Erase memory of one who committed an extreme act (often for the purpose of gaining fame for themselves). Erasure of the actor’s existence, penalty for speaking of the person. Occurs as a top-down act rather than bottom-up.

- “First-order: Prevent others from committing similar acts.

- Second-order: Memory can remain longer because the damnatio memoriae penalty is incurred. Hard to actually achieve. Also hard to know when successful.

- “Examples: Herostratus (burned down the Temple of Artemis), and a range of deposed or cruel Roman and Egyptian emperors.

“Modern examples include the downplay of celebrity suicides so that others do not copy them. The “Werther effect” increases suicides in others after a widely publicized (often celebrity) suicide…

“When Kurt Cobain shot and killed himself in 1994, his widow went on TV to say that what he did was wrong. Cobain’s death then did not result in others’ killing themselves. Robin William’s suicide 20 years later, however, did result in more deaths as the story spread widely.”

A “page two” approach is to think of the way many people today learn about and seek to validate what events actually happened: from the Internet.

Taking a page two approach, in order to erase someone from history, don’t actually erase them. That only builds interest in who they were. Instead, push up the relevance for something else similar. Make it difficult to discover the very thing you are trying to hide.

For example, push a preferred story to page one since few people visit page two. Or associate the targeted story with something ridiculous that swamps the formerly more important set of events.

Your Great Grandchildren Are Outraged

If the reevaluation of historical figures becomes the norm, we might even extend it to people without historical significance. How would your future descendants look back on your life?

Morals and acceptable behavior changes over time. If you are remembered long enough and have enough documentation on things you did, even those that were minor parts of your life, it’s a matter of time before people find your actions outrageous, if not actually disgusting. Your great (or great-great-great) grandchildren will not only be embarrassed of you, they may actually loathe you. Being seen as a sponsor of racism and eugenics is a target today, but what tomorrow? (Creators of top-down systemic risk, I hope.)

A view of history could then look like this.

What do these historical reevaluations or erasures do for the present?

It’s curious to see the modern version of historical erasure. This version removes the old names but also criticizes the present. Unlike the examples from Stalin or Mao (removal as a way to look better), today does removal make people look worse?

How might you avoid the outrage of your great-grandchildren (or great-great-great… grandchildren)? Especially if mainstream (though divisive) ideas of the past show us change in morals and acceptable behavior.

One approach is to survey social changes of today, at least in your home country, and carry them forward. But what if social concerns 100 or 200 years from now are unexpected? What if those future concerns are fringe concerns today? Or what if those future concerns are actually outrageous today?

Consider

- When do countries or people choose histories that make them feel worse?

- Should all historical figures have their worst sides presented as well as their best? Do simplistic positive-only histories benefit or harm?

- The evaluation of religious heretics sometimes results in the erasure and condemnation of an individual years afterward. I just didn’t expect religion to be a good comparison to today.