In an earlier post (Do We Create Shoplifters) we saw how a changed environment can change behavior.

That post focused on tech development with behavior change for the worse. In this post, rather than tech, I focus on good intentions that give no thought to second steps, or how a system may change. These good intentions backfire.

Let’s look at the unintended outcomes of otherwise well-meaning system changes in education, forest management, and hiring.

More University Graduates

In the US’ evolution to a knowledge economy students needed more years of education than in the past.

If higher levels of education would help this economic evolution happen faster, how could the government improve its young citizens’ chances? Make it easier to pay for college tuition with student loans.

But student loans are different from other types of loans. The lender does not consider the creditworthiness of the students or the new earning ability their chosen degrees may provide them to repay the loans. It’s quite easy to take out a student loan in comparison to other types.

This policy produced the unexpected drawback of higher college tuition without greater student ability to repay.

From the Wall Street Journal article “Student Loan Losses Seen Costing U.S. More Than $400 Billion:”

“After decades of no-questions-asked lending, the government is realizing that it has a pile of toxic debt on its books. By comparison, private lenders lost $535 billion on subprime-mortgages during the 2008 financial crisis…

“The effect this time is different. The government, unlike private lenders, can borrow trillions of dollars at low rates to absorb the losses, without causing a panic…

“The absence of a cataclysmic event like the financial crisis is removing the impetus for the federal government to change its lending practices, which analysts said have enabled colleges to raise tuition far above the rate of inflation.”

The strange thing for me in complaining about this situation has been seeing just how long others have also complained about the situation. Here’s former Secretary of Education William Bennett in his “Our Greedy Colleges” NYT Op-Ed, written in 1987:

“If anything, increases in financial aid in recent years have enabled colleges and universities blithely to raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase. In 1978, subsidies became available to a greatly expanded number of students. In 1980, college tuitions began rising year after year at a rate that exceeded inflation. Federal student aid policies do not cause college price inflation, but there is little doubt that they help make it possible.”

Where else do the tuition increases come from? As I wrote in The University Fundraising Arms Race:

“Most of the cost of university tuition is not the education… [T]he pure education piece of university tuition (larger than just faculty) seems to be estimated at somewhere between 17% to 25%, depending on the institution. Faculty salaries are pretty flat over the past few decades and more faculty are now hired on a part-time basis in order to keep costs down. There has, however, been a large increase in the number of university administrative jobs.”

These cost increases – and passing them along to students – would not have been possible without the loan programs.

Impacts of higher tuition include changing the types of jobs graduates can take, diversion of what would have been disposable income to loan repayment, less risk-taking, deferring home ownership, and more.

When you want to encourage more of something beneficial, you might also encourage more of something else detrimental.

Wildfires Worsen

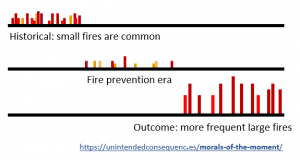

The US Forest Service was started in 1905 in part to reduce forest fires. The result of that policy was forests with a much higher tree density than naturally occurred otherwise.

Other changes include that around 1900 settlers of the western US introduced livestock that ate grass, which in turn removed potential fuel for smaller fires, and enabled smaller trees to grow.

After a hundred years of fire prevention, you end up with very different forest density. As the fire manager of Santa Fe National Forest noted: “On this forest, it’s averaging about 900 trees per acre. Historically it was probably about 40.” The result is a much bigger fire risk than previously.

After this tree density problem built up for a century, how do you reverse it?

Even if you could thin out the forest, what happens when there are few timber companies in the area? Or could you burn the cut trees safely?

The wildfire problem is also a case of the long reach of short-term interests. We would be able to put up with short-term inconvenience in the form of smoke from smaller fires otherwise. Instead we produced a perverse result the opposite of what was desired.

Attempts to reduce small problems lead to bigger problems.

Ban the Box Backfires

Ban the Box is a campaign to remove the check box that asks job applicants to disclose whether they have a criminal record. The intent is to improve opportunities for released criminals.

It sounds like it makes sense. After all, higher past crime levels and the criminalization of drug offenses dramatically increased the number of people with criminal records. Without that increase, Ban the Box may have never been proposed.

And if you can help people with criminal records find jobs that would help reduce future crime. That’s the impact that Ban the Box sought. Originally stated in 1998, currently 36 states, 150 cities as well as federal job opportunities (starting 2015) have implemented Ban the Box.

Given that proportionally more ex-criminals are minorities, the theory was also that having a disclosure box also harmed minorities’ job prospects.

But the reality turned out to be very different.

Amanda Agan and Sonja Starr researched the effect of Ban the Box by sending “15,000 fictitious online job applications to employers in New Jersey and New York City, in waves before and after each jurisdiction’s adoption of BTB policies.”

From their paper Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Statistical Discrimination: A Field Experiment:

“[W]e find that the race gap in callbacks grows dramatically at the BTB-affected companies after the policy goes into effect. Before BTB, white applicants to BTB-affected employers received about 7% more callbacks than similar black applicants, but BTB increases this gap to 45%.”

Beyond the callbacks, Ban the Box has been attributed to a 5.1% decrease in probability of employment in young, low-skilled black men and a 2.9% decrease for young, low-skilled Hispanic men.

Here we have a policy that intended to increase fairness for ex-convicts but instead produced an unexpected drawback of increasing racism. That is, the 7% racist hiring practices above grew to 45%, without a change in hiring managers.

How do you reduce this impact when job applications do ask for criminal record disclosures? There are other movements to reverse this outcome, such as the REDEEM Act, which would allow nonviolent juvenile offenses to be expunged or sealed.

But what about just adding the box back? This is the simplest solution, but after years of promoting Ban the Box, would its proponents agree? Would employers pushback against a change?

Attempts to improve outcomes for one group lead to worse outcomes for another, larger group. Good intentions with bad outcomes.

Problems of the Moment

Each of the above examples involves trying to remove a negative outcome at its endpoint rather than at its cause. Better firefighting rather than better forest management. Easier access to loans rather than reducing tuition. Removing information about criminal history rather than reducing the number of people incarcerated.

I believe that anyone involved in developing the policies above may have had the best of intentions, but didn’t care to study the potential outcomes.

In Dietrich Dorner’s book The Logic of Failure, he details the experience of test subjects playing a resources management simulation. Managing resources in the invented region of Tanaland or a town called Greenvale, the participants often made decisions that impacted their simulated inhabitants negatively.

Dorner reflected on potential reasons for that.

“It appears that, very early on, human beings developed a tendency to deal with problems on an ad hoc basis. The task at hand was to gather firewood, to drive a herd of horses into a canyon, or to build a trap for a mammoth. All these were problems of the moment and usually had no significance beyond themselves. The amount of firewood the members of a Stone Age tribe needed was no more a threat to the forest than their hunting activity was a threat to wildlife populations. Although certain animal species seem to have been overhunted and eradicated in prehistoric times, on the whole our prehistoric ancestors did not have to think beyond the situation itself. The need to see a problem embedded in the context of other problems rarely arose. For us, however, this is the rule, not the exception.”

Those earlier local impact days are largely over. Increasingly, our interconnected actions, including those from top-down policies, can cause widespread harm as well as improvements.

Still, reversing the above examples would create unintended consequences as well.

Morals of the Moment

I believe we create some of our worst outcomes when we lead with morals to find solutions.

Leading with morals makes it uncomfortable to disagree with the reason for doing something. Or do you want students denied an opportunity at college? Or is it you want forests to burn? Or do you want to deny people a fair chance at employment?

When we lead with morals we also more easily fool ourselves. I doubt that proponents of any of the policies above really wanted the outcomes their policies produced. But those paths were made smoother by believing that they were doing the right thing.

The appreciation for unintended consequences means that we might sometimes hesitate to choose options that seem morally correct.

Consider

- As Richard Feynman said: “It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong.”

- Should we have a policy reversal clause if target situations significantly worsen? Or if adjacent situations worsen as a result?

- As Thoreau wrote: “For every thousand hacking at the leaves of evil, there is one striking at the root.”