Change often doesn’t happen smoothly, but rather in fits and starts.

Here’s a look at some mass actions over the past few decades that either caused fear or fury and (for some of them) how they were ultimately forgotten.

Since we’ve seen a year of fear and fury around the world, largely in the form of many types of large sustained protests and the impact of COVID-19, let’s look at some past examples and how change plays out (or doesn’t). What behavior and consequences emerge along the way?

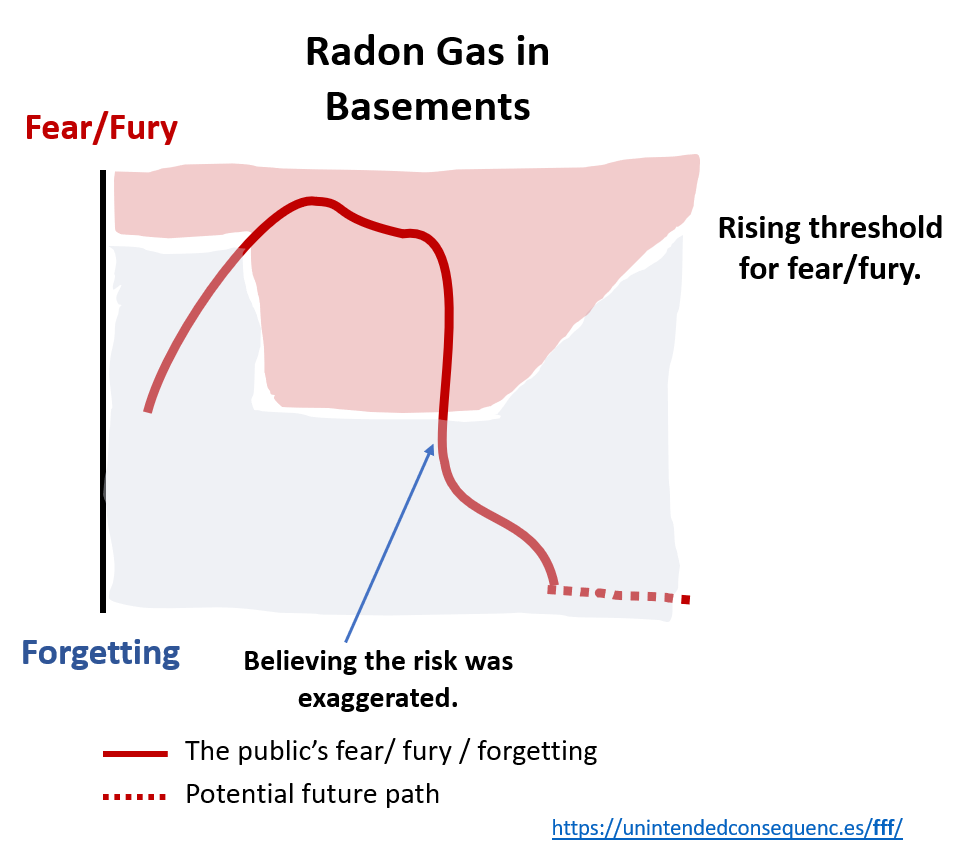

Radon Gas. In the 1980s a report from the EPA and its reporting in media set off a radon gas scare in the US. The gas, naturally occurring in the ground, seeped into home basements and was blamed for cancer deaths. People suddenly became afraid to spend much time in their basements. But the risk was exaggerated in importance.

Radon gas as a cause of cancer is highly tied to smoking. Given that smoking has declined in the US over the last few decades before the recent creation of vaping, is radon really an issue? An EPA report estimates that 21,000 die of lung cancer caused by radon but 86% of them are also smokers.

With more knowledge, the fear dissipated like the gas itself.

Occupy Wall Street. It was a Canadian publication that kicked off this movement, in September 2011. The first location, at Zuccotti Park, a short walk from Wall Street in Manhattan, held a mass of supporters for about two months. Protesters created new ways to communicate in a noisy urban environment without electronic amplification (the human microphone) and vote (hand motions).

But the movement had few lasting effects. It was a movement of protest rather than goals. While other Occupy locations sprung up around the world, their impact was minimal (and mostly forgotten).

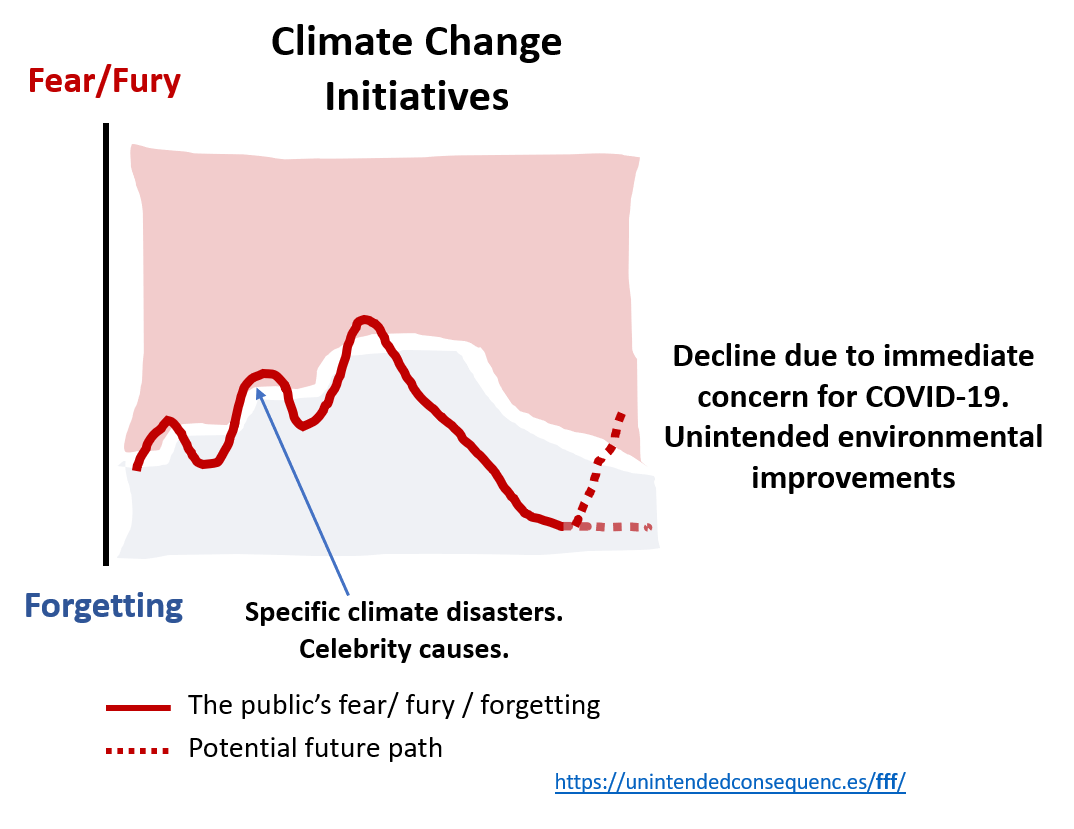

Climate Change. The difficulty with climate change as a movement is that it is long-term and slow-moving. Climate scientists recognize that they are still learning to model outcomes of increased greenhouse gases. The most famous of international agreements, the Paris Agreement of 2015, by definition does little to combat climate change, even if all signatories live up to their carbon reductions.

But regardless of inability to model global warming outcomes (or anything years in advance), countries look at efforts to reduce climate change as practicing the precautionary principle. I believe the intent is correct — we should try to minimize potential big and maybe irreversible risks of climate change. But there has been little discussion of the risk-reward trade-off or solutions that have sustainable business models. Movements that are celebrity-centric are also at risk of fading as the next new thing comes along.

Nuclear Winter. Since climate change often means warming, I’m including a preoccupation with the opposite outcome — that of a nuclear winter caused by hundreds of nuclear warheads detonated around the world. The belief was that the resulting firestorms and soot would reach the upper atmosphere and block sunlight.

Nuclear winter was a common fear of the 1980s. Unlike global warming or climate change, nuclear winter had a more immediate feel. It could be triggered at any moment, could possibly be initiated by a mistake, and would be irreversible for years.

However, there were critiques of the model’s assumptions that much soot would reach the upper atmosphere, how much sunlight it would prevent from reaching earth, and more broadly of the likelihood that hundreds of cities around the world would “firestorm” in the event of an all out nuclear war.

As Freeman Dyson said in the mid-1980s: “It’s an absolutely atrocious piece of science, but I quite despair of setting the public record straight…. Who wants to be accused of being in favor of nuclear war?” And Prof. Victor Weisskopf of MIT: “Ah! Nuclear Winter! The science is terrible, but, perhaps the psychology is good.”

It’s interesting that the Carl Sagan quote that heads up that previous link:

“Apocalyptic predictions require, to be taken seriously, higher standards of evidence than do assertions on other matters where the stakes are not as great.”

was at odds with the place the science reached. The model was put to rest when effects weren’t seen after a natural experiment: oil wells set on fire by the Iraqi military retreating from Kuwait in 1991.

Long time readers of my articles might remember that I earlier covered the two other defunct ideas the linked article mentions (the “Energy Crisis” and the “Population Bomb”) in my post on the Self-Defeating Prophecy.

COVID-19 related. Here are a few examples of fury, fear, and forgetting from the recent COVID-19 world.

Liberty University reopening. Liberty University is an evangelical university, with its student body largely online. It made news in March with a decision to reopen its campus just a couple weeks after sending students home in the early part of the COVID-19 lockdown. Critics broadly panned Liberty University’s president for the decision. I attribute part of the criticism to the fact that the university is religious and conservative, but objectively it did seem to be a foolish decision. Why take the risk so soon? So what actually happened?

First, only 1,200 of the 15,000 in-person students decided to return to campus after reopening (most students are online only). Second, the combination of ease of social distancing (few students returned) and other health safety precautions appear to have worked. No students or workers on campus came down with COVID-19 (not counting those studying or working remotely, of course). The story has largely been forgotten.

(I meant to revisit Liberty University’s results myself but the Wall Street Journal beat me to it.)

Hydroxychloroquine. The ongoing story on hydroxychloroquine and zinc as a potential coronavirus treatment is fascinating. Not necessarily because of the science, but because of the politicization of the science. Will the drug be shown to be helpful, helpful in certain conditions, or generally harmful? I don’t know. There have been studies and retractions in multiple directions. As I write this, the FDA has ended emergency support for the treatment.

But previous support or opposition for the drug fell largely on political lines, with Trump supporters or Republicans in general in support of it (or at least believing the risks are worthwhile) and Democrats (or Trump opponents) believing that hydroxychloroquine and zinc are either harmful to COVID-19 patients or that even if helpful, a run on the drug would cause shortages for others taking it for malaria or lupus.

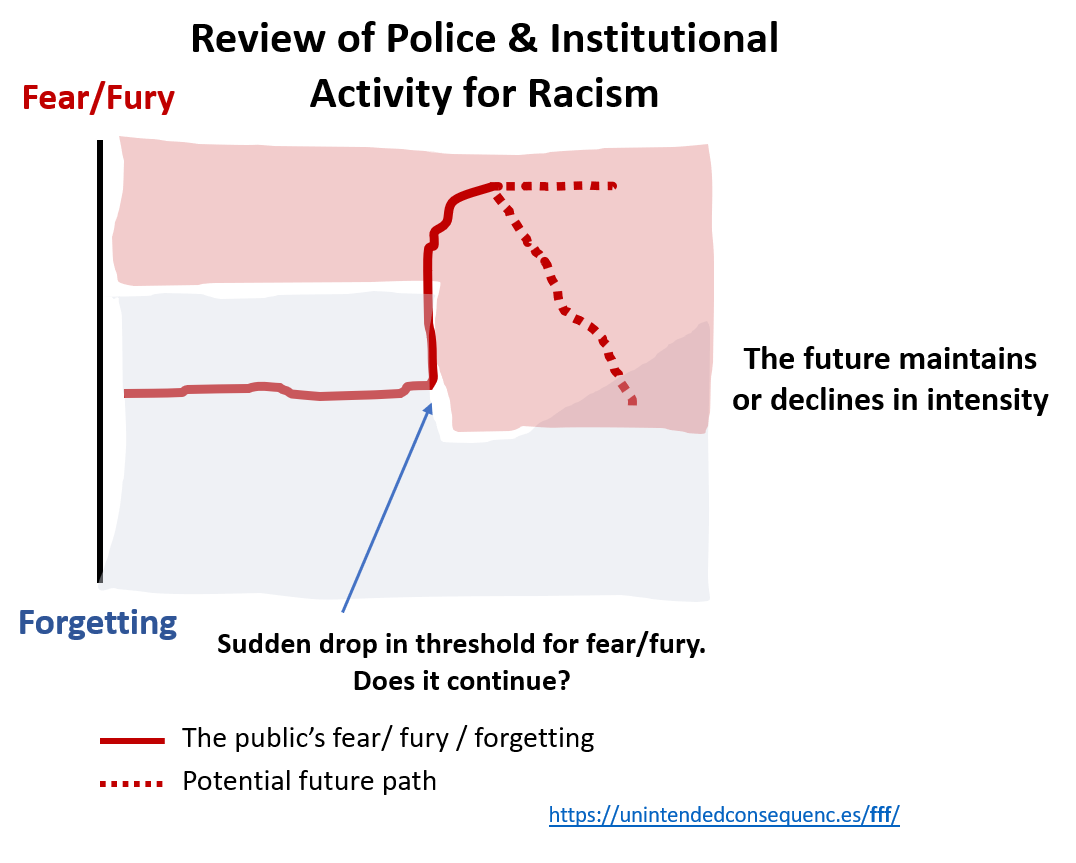

Black Lives Matter / George Floyd protests. The number and size of national — and international — protests that George Floyd’s death inspired surprised a lot of people. I put these protests in the COVID-19 category because I think having large numbers of people isolated at home built up energy that became channeled into the protests, making them larger than they would have been otherwise.

The question longer-term is what are the goals for change and what are some steps to get there? While the protests are more uniting than the Occupy movement, will they have as much impact as it seems?

The COVID-19 related examples are new enough that we don’t know how they will end up. What’s clear is that any of the social movements that want to see change must use the attention they have to try to force change while guarding against forgetting.

Patterns and Overshooting

There are some qualities needed for the fear, fury, and forgetting pattern.

Latent Problem / Context. First, there is a latent problem — one among many that may rise up as the problem. There must be something there, whether provable or believed to be true.

Triggering Event. Then, a triggering event sets people into action. For the BLM protests it was the deaths of Floyd (and Arbery and Taylor) within a short time. For radon gas it was continued news reports. For nuclear winter, it was esteemed scientists publishing their theory. For Liberty University it was going in the opposite direction of other schools.

Fury or Fear. Depending on the type of problem and timing, it presents itself as fear or fury. We see an accelerated growth in problem-related interest and action. Fury can get people out protesting. Fear can keep them in.

Forgetting. Finally, the whole thing fades as the reality changes and people forget.

How does fear and fury overshoot? These are the other ideas I’m exploring.

The Overshoot — Fear and Fury. When the target of attention is pro-establishment (in the recent examples, meaning aligned with Trump, whatever that means) there’s a tendency to over-fuel the reaction. If there is a general equality of how people choose their actions regardless of the political side they’re on, then the anti-establishment side will tend to overshoot in their reaction. That means more fury and fear and then more forgetting on the anti-establishment side.

The Overshoot — Forgetting. Some events build up, are forgotten, and then years later people conclude that they must not have been such a big deal. This leads people to mistrust the groups that led them astray. Currently we see that mistrust with climate scientists and news organizations. It provides critics with counter-examples and makes it more difficult for the same group to get attention in the future.

The Overshoot — Maintenance. When a problem lasts long enough, entities appear based on assessing it or addressing it. That is, there emerged a set of businesses with business models around radon testing, selling products that are supposed to be better for the environment, and measuring racism. These businesses need to evolve as the problem becomes less bad. Otherwise, they just maintain the status quo in order to maintain their business models.

Forgetting is Bad; Forgetting is Good

Movements run their course. A cause that fills streets with passionate supporters fizzles out. A popular goal backed by logic lies abandoned.

This is infuriating to whom I’ll call the true supporters (those who would support their cause even if everyone opposed them). And this is perhaps not even noticed by those others who backed the cause out of peer pressure just for a while.

But the fact that some movements and causes run their course without follow-up or actual change is not necessarily bad.

Where does this forgetting come from? What causes it? I see a few sources of forgetting.

Exhaustion. Some causes require such devotion that eventually people run out of energy. Especially if they make no progress, former supporters decide to put their energy elsewhere.

Disproof. Potential supporters, presented with new facts, change their beliefs.

New shiny object. Fashion changes even before the creation of the fashion industry. Why would we expect anything different from causes?

Changed supporter demographics. That is, the people who once backed the cause, for example when young and single, are now older with less time and more responsibilities and a different view of risk.

Consider

- What becomes the next movement is partly determined by popular support and partly by timing.

- What becomes a lasting change is partly determined by how much change could be packed in during the fear and fury phase.

- Reality changes less than its perception.