We are in an early transition period of omniscience. We are transitioning from some personal actions that are recorded only through our memories to many events being recorded, re-playable, and shareable. By “personal actions” I mean anything from what content you consume to where you go to how you act. By “re-playable and shareable” I mean that some device or system collects data that can be stored for any length of time and then easily sent to others to observe.

Traditionally, there is anonymity in a city. Outside of your specific neighborhood (if you’ve lived there long enough) and specific places you frequent, it is possible to just be a face in a crowd. Not so in a small town where more people know each other (or have even grown up together). That’s one reason why cities have historically been liberating — there are less reasons to be held back by standards of those who have set expectations of you.

But anonymity in cities has been slowly eroding. Placement of video cameras is a leading cause of that. But the erosion has older, analog roots.

My dad used to tell a story about a time he went to see a movie about Russia during the McCarthy era. As everyone left the theater, a photographer took pictures of them.

Was it a coincidence? Or did watching that movie mark you as a Communist sympathizer and put you on a watch list? Either way, think of the manpower required to identify people from pictures in the 1950s. The effort would have been immense without other data.

The effort would also have been unwarranted without other needs. Does attending a movie mean anything? In the McCarthy era US, an act like attending a movie might be twisted in any way. It’s a form of “the clip” discussed earlier. But the reality could also be that you left the movie convinced that Communism was worse than you thought. Maybe you attended because you wanted to understand an enemy. (The movie was non-political and about the natural environment, so who knows?)

In the 1950s, if you had the data, the willingness, and the time for a longitudinal study, maybe a large organization could just about put together a statistical analysis of the likelihood of your Communist sympathies, having chosen to watch a movie. It could then preemptively act.

But one thing that could not have happened back in the 1950s is the automatic recognition of each attendee by capturing their images from cameras mounted by the theater’s exits and using facial recognition. The tech that enables doing that at scale just didn’t exist.

Fiction

There’s a belief that photos protect the innocent. Does that depend on context? As in, who decides innocence?

“All previous crimes of the Russian Empire had been committed under the cover of a discreet shadow. The deportation of a million Lithuanians, the murder of hundreds of thousands of Poles…. remain in our memory, but no photographic documentation exists; sooner or later they will therefore be proclaimed as fabrications. Not so the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, of which both stills and motion pictures are stored in archives throughout the world.” – Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

In Kundera’s novel his character Tereza is a photographer whose photos of protests later are used to identify the people who protested. There, I suppose, with large numbers of people involved in state security, it was possible to identify enough people manually from their photos.

But doing that automatically, at scale, even where there is no call to note anyone’s action is a differently thing entirely.

What Does It Mean To Be a Photographer?

Because of my dad, I eventually learned to use a camera. I preferred semi-automatic film cameras and a range of lenses, especially wide-angled lenses that encouraged closeness to the subject.

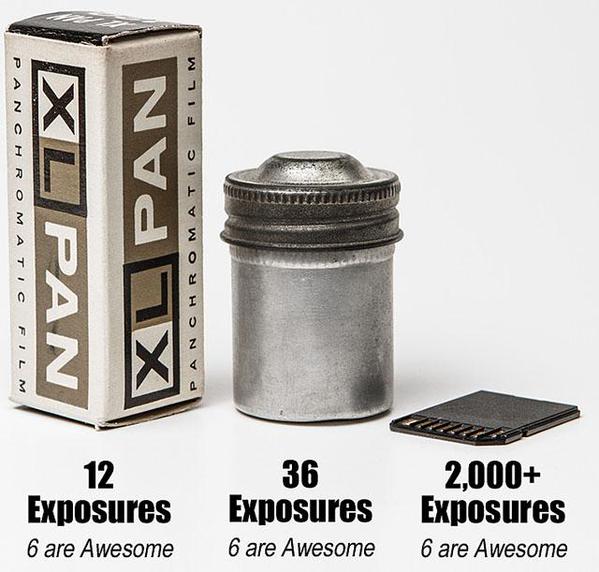

Images used to be expensive, both in money and time. The cost of roll of film, developing, and printing kept you naturally selective about the pictures you took. The time that it took to be able to see the prints meant that you had to be able to visualize what the photo would look like before it was printed. This was not the same thing as just looking through the camera’s viewfinder. You really had to be able to imagine what the print would look like after you got to the darkroom.

Now images are cheap and immediate.

And now I’m probably on camera hundreds of times a day.

The above image needs to be updated, with another part of the progression — which I added at right.

What new behavior emerges as people are on camera everywhere in public and images may be processed and shared easily?

We could see emergence of a Techno Richelieu effect. That is, Cardinal Richelieu’s supposed quote “If one would give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest man, I would find something in them to have him hanged,” can turn into something like this:

“Everyone breaks the law — at least in small ways — every day. But now there’s evidence.”

And then this:

“Massive amounts of recorded evidence will mean that everyone will eventually show themselves, by statistical analysis, likely to be guilty of something.”

A funny example (well, kind of) of this was from one of China’s facial recognition implementations. Dong Mingzhu, founder of equipment manufacturer Gree, who was accused of jaywalking after facial recognition wrongly targeted her picture on an advertisement placed by a crosswalk. The mistake was eventually realized. But Ms Dong is a billionaire. How many mistakes will be corrected for others?

Especially since facial recognition can be said to have benefits and these benefits will sell the rest of this tech implementation. If a wanted criminal can be identified in a stadium within a group of 60,000 fans, it’s hard making a logical argument that use case is a bad thing. Still, I also think many people would say that something just feels off.

Related to that, San Francisco became the first US city to ban facial recognition tech used in public.

“As the Board of Supervisors noted, there is a fine line between ‘good policing’ and becoming a ‘police state’, and the recent rapid improvements in facial recognition technology (which now enable near real-time tracking of individuals, even in large crowds) have raised many concerns that the technology was advancing too far, too fast… It is important to note, however, that the ban on facial recognition technology for city agencies does not apply to private individuals or private businesses.”

Sounds like the ban will spread to other locations but something makes me pause. That term “too fast.” Facial recognition tech seemingly sprouted up suddenly, which was part of the reason behind the push-back. I say give it some more time and the use cases for the tech will overpower the privacy concerns.

Business Models

We look at the examples of deployment of facial recognition tech in test cities in China and elsewhere. To many people, this feels scary, like a privacy invasion, and an unnecessary one. Still others take exception to certain applications of the tech, such as tracking people in public places (but not other areas) or allowing it at high-risk locations such as airports, but not on the street.

Whether this tech is expensive or cheap today depends on how you judge the value that the installer gets from it. In general though, it’s still expensive. But this will change. In fact, the hardware will probably change in a predictable way. We generally understand how components get cheaper over time.

Why does the capability for facial recognition at scale even exist? This depends on a few factors.

- Camera technology needed to become cheap enough to make deployment of millions of devices affordable. Like most tech, components that go into networked cameras fell in price over time. Inputs of that are Moore’s Law, commodification of components, economies of scale, and a manufacturing sector that can produce hundreds of millions of devices. The tech to network the cameras and share visuals and location.

- The collection of multiple examples of individuals’ appearance matched to their identification.

- The facial recognition tech that ties it all together.

- The business models that make facial recognition deployments sustainable. Some, like those in China today, are heavily supported by government funding. Soon though, there may be sustainable business models for these deployments, from consumer data, infrastructure usage, social fairness, behavior modification, and more. The threat of terrorism may only need to be called upon initially.

These changes will drive a different business model that will push past public opinion on privacy.

The Watched Are Different

What if it’s a positive thing to be watched? A famous old experiment into factory lighting conditions produced an unexpected result: that people who knew they were being watched were more productive. This came to be called the Hawthorne effect, after the name of the factory where the experiments took place.

But used today with wide-scale camera implementations, the results are different. This is an example of how things are different at scale. Or, in the realm of privacy, according to Bruce Schneier, “in security, technology scales badly.”

As deployed for a social credit score, as in test cities in China, why not encourage people to be better? It’s that the same tech is also used as a means of control, for example through mass surveillance in Xinjiang Province. The famous actual implementations of facial recognition tech are not about positive behavior. Or maybe we just differ on what positive means.

Considerations

- When tech trends are inevitable, they will drive new business models. These new business models will drive new values. Eventually, we will forget the old values.

- Like profiling, statistical likelihood (the Techno Richelieu effect) will be a “good enough” approach to law enforcement at scale.

- What other reactions and new systems will emerge?