With decisions come opportunities for unintended consequences, especially when when success and failure are radically different. How do we make a decision in a high-risk environment? What advice do we take in, how do our desires affect us, and what happens if this is a one-time game versus a multi-time game?

Here I’m going to look at two very different decisions that people make: how to run a startup and how to choose between options for a serious health issues.

Less Serious, Relatively Unpredictable Outcomes

I’ll focus on a few potential paths a startup founder has to build their business.

- Build something scalable and raise capital to support growth,

- Bootstrap (fund via customer sales) to reach business sustainability,

- And what I’ll call building a disposable startup, or a company that is built to improve the odds of what the founders will do after they shut the startup down.

Let’s look at each option. The most publicized startup path is the scalable business fundraising path, even though startups raising outside capital account for less than 1% of the overall number. The attention we put on this business type makes it seem more achievable and better than other options. Media headlines go to companies that raise lots of capital, the tiny fraction of companies that raise large amounts become household names, and many study how to run this business type. I have met potential founders who can talk about the ins and outs of term sheets before they have actually built anything.

Bootstrapping founders are those who build their business so that they can charge customers early and use that revenue to sustain the business. These companies may have less potential to grow big, but they can often support a single founder or a small team.

And then, what I call disposable startups are run by people who build for different reasons. The reason could be gaining operational experience, regardless of whether they plan to pursue the company – or something a bit different.

I have seen some disposable startup founders go through the motions of building a startup, only to realize partway through, or even before they began, that calling oneself a startup founder opens other doors. In the US at least, the doors opened are meetings with potential investors, networking more broadly than if they didn’t have a startup, and a potential setup for a position in a VC firm or funded startup. Founding a startup can be a resume builder in a way that other work cannot. I have seen people do this both intentionally and unintentionally, realizing along the way that their options have changed. This technique is not used very much in places where less value is put on building a startup.

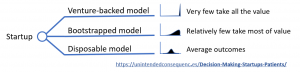

The breakdown of these decisions and their potential outcomes looks something like this.

Second-order effects of the startup types include: high-growth startup investments producing a low success rate that affects founders more than investors and disposable startups that waste mentor time and startup program support.

In the startup examples, founders need to believe that they are the exception or need to be ignorant of how uncommon success is. Outcome distributions are wildly different.

As Steve Blank said to a group of startup founders, “There are 500 people in this room. The good news is, in ten years, there’s two of you who are going to make $100 Million dollars. The rest of you, you might as well have been working at Wal-Mart for how much you’re going to make.”

More Serious, Relatively Predictable Outcomes

Terminal cancer patients have a more serious decision to make but miss opportunities to include outcome statistics in their decision-making process.

In a paper titled The Lake Wobegone Effect: Are All Cancer Patients Above Average? we hear a little bit more about how this happens.

The paper uses an individual patient’s case to highlight the difficulty cancer patients, their families, and doctors have dealing with patient decisions and outcomes. In the paper we learn about patient Nancy Wolf, diagnosed with lung cancer at age 79, and the series of treatments she received until her death at age 80.

Interestingly, Nancy’s situation involved a family that was more educated about health and outcomes than typical (two family members were actuaries while others had worked in the healthcare industry). But Nancy experienced worse outcomes than she might have had she only looked to statistical outcomes.

Similar to the VCs above who might push a portfolio company to spend more on growth in order to have the chance to recoup multiples of their investment, something comparable happens with doctors treating cancer patients. Like the investors, the doctors don’t directly suffer the downside of a bad decision. But doctors’ backgrounds certainly determines how they present options to their patients.

Nancy first learned of her cancer when, at age 79, her physician ordered a chest X-ray even though there is no recommendation for such a health screen for patients of her age. In her case, the X-ray showed masses on her lungs which turned out to be non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Unlike the startup example, taking strong guidance from statistics is probably much more helpful for cancer patients. There are more similarities between outcomes for patients than for founders. But patients and even the doctors – the experts in this situation – often remain ignorant or biased against survival statistics. In one study, doctors were found to overestimate odds of patient survival by 5.3 times.

In terms of decision frequency, there are some similarities between startup founders and these patients. Many startup founders can make only one attempt if unsuccessful (they are out of savings or time). For patients with terminal cancer, decisions are one time only.

However, investors and doctors guide these decisions many times over their careers. In the case of startup investors, investors benefit from big wins. Therefore, investors may encourage founders to “go big or go home” and invest in growth, sometimes at the expense more likely smaller successes. In the case of the doctors there may be a bias as to what they can achieve in each patient’s situation. Rather than compare their likely patient outcomes to all outcomes, doctors may believe that they can deliver better results, or may even be ignorant of the statistical outcomes, or how to think about them. Doctors also skirt around the issue of mortality with their patients. From The Lake Wobegone Effect: Are All Cancer Patients Above Average:

“…Nancy met with Dr. O1, an oncologist, to discuss follow-up

treatment… He also informed her that although only 50 percent of stage IIB patients who eschewed chemotherapy survived for five years, 60 to 65 percent who did have chemotherapy survived for that long.“Herb and Kevin [her husband and son], both actuaries and present at the appointment, asked Dr. O1 if Nancy’s age, then seventy-nine, would make it harder for her to weather chemotherapy. In response, Dr. O1 admitted that most NSCLC research subjects were younger than Nancy. He then revised downward his five-year-survival-without-chemotherapy estimate, to below 50 percent. When the two actuaries pointed out that as a seventy-nine-year old, Nancy’s prognosis was also likely bleaker than studies indicated even with chemotherapy, Dr. O1 offered anecdotal evidence supporting treatment. He noted that a current patient, now seventy-seven, was still alive one year after four rounds of chemotherapy.”

The mean age for research subjects in related studies was about 60, or almost 20 years younger than Nancy. Further, the side effects of cancer treatments can be severe, with 30% suffering “severe and/or permanently disabling” effects.

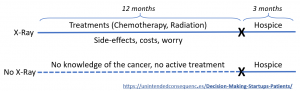

In Nancy’s case, she was later put on the drug Tarceva, which while expensive, statistically only delivered an added two months of life, often coupled with “severe, disabling, and fatal toxicities” at the rate of 35% for patients over 70. Other data suggested that patients choosing only palliative care had better survival rates (the aggressive treatments cause more harm).

For Nancy, the year of treatment was one of side-effects, added worry, and financial cost estimated to have added no extra time or quality of life.

Nancy’s potential decision paths at age 79 looked like this.

The difference between making serious health decisions and startup decisions is expected outcomes. For high-growth startup founders, outcomes are skewed so that a tiny fraction receives almost all of the benefit – and the benefits are 100s or 1000s of times that of everyone else. We don’t see this in health outcomes. (A comparable would be to see treated patients have the positive outcome of being able to live an extra 500 years.)

As a result, it might make sense to ignore startup probabilities and go for that tiny chance of a huge outcome. It also makes sense to pay more attention to the likely outcomes for health concerns.

How could we improve the way we make these decisions?

- Make the statistics available and understandable for the background of each patient. Develop a “game” that people can play to understand health outcomes before they must make their decisions.

- Know that it makes more sense to behave in a statistical way for terminal cancer and other serious illness treatment. Know that startup founders may have other desired outcomes than assumed.

- Understand your risk profile and find a way to challenge expert advice.