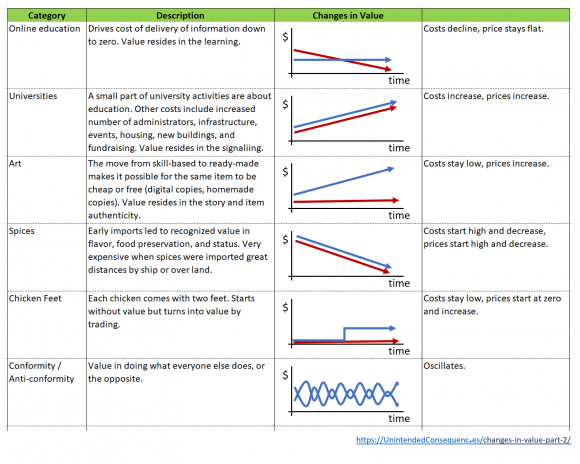

While I discussed silver, tulips, and drugs in Changes in Value Part I, here I look at education, art, spices, chicken feet, and conformity. What systems influence the value of things? Why does value change?

At the end I provide suggestions to assess your own situations.

Education

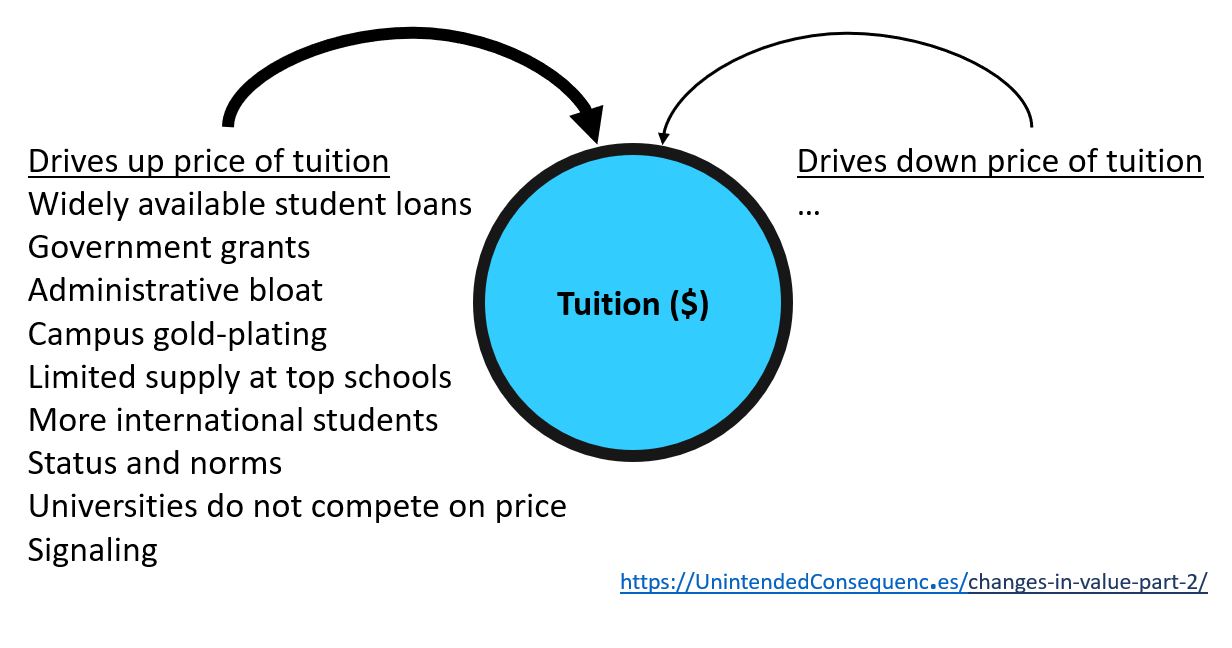

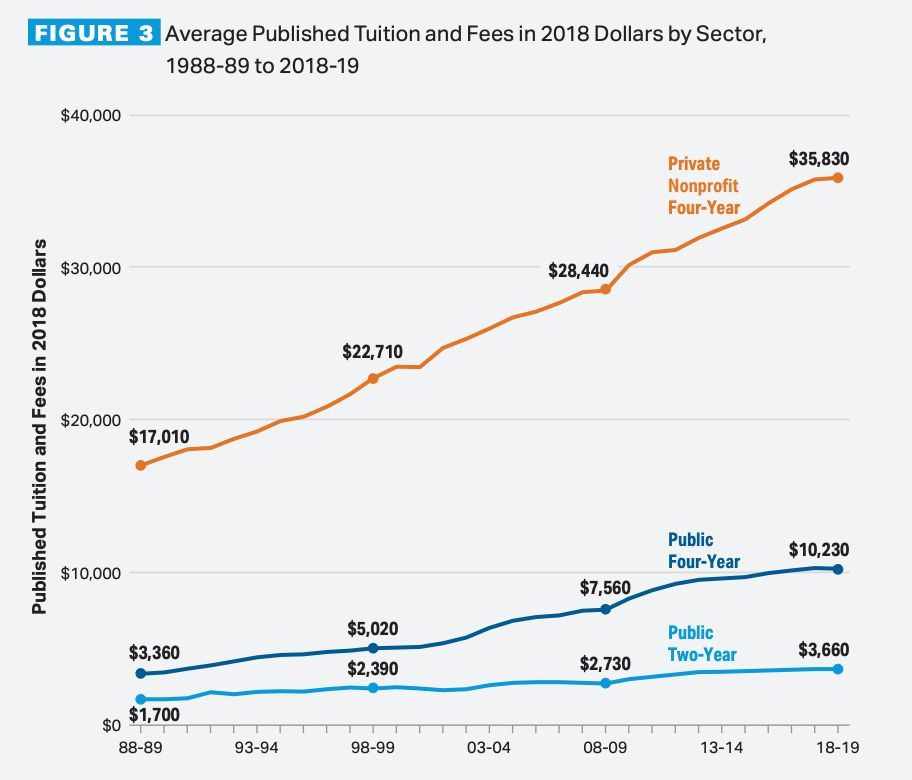

I’ve been critical of higher education on this blog before, but for other reasons. When it comes to the the price of a college degree — and here I’m mostly talking of the price of American college tuition — we’ve seen a doubling in price, adjusting for inflation, over the last 30 years. A number of factors combine to drive up the price.

In The Case Against Education, author Bryan Caplan claims that the value of higher education is mostly (80%) in signaling. That is, by completing a college degree a student demonstrates their ability to finish something difficult (four years without quitting) and patience to sit through boring classes (and therefore boring company meetings). They are less likely to be a flighty employee who quits out of impatience or boredom. As long as companies value those traits, college degrees have value. And this is value that can’t be faked — you actually have to take the time to complete the degree to get the diploma.

Does education need to be expensive? Of course not. There are multiple free or nearly free sources of learning from the public library to online courses. Does college education need to be that expensive? No again. Very little of tuition dollars (around 5% to 20%) goes to the education part of college.

But the requirement to complete a degree and the value that is delivered in earnings and opportunity, for most graduates, keeps applicants coming. Having a diploma (and knowledge) is viewed as more valuable than having the knowledge alone. Otherwise, online classes would have already replaced traditional universities.

Further, growing wealth around the world meant that universities that attract international students could continue to increase sticker-price tuition (typically international students pay full fees) while discounting tuition for domestic students through scholarships (not reflected in the published tuition figure). The easy availability of student loans for Americans also makes paying for college easy — while you are a student. A different story after graduation, depending on individual earning potential (school, major, and industry all play a part) and timing (graduating in a good market or a recession).

Signaling, international demand, easy loans, and actual benefits all contribute to support high tuition.

Still we may be close to a tipping point here. As some students choose to take a COVID-19 leave of absence the university system may start to change.

Art (readymades)

The image below is of a fluorescent light bulb, also going up and to the right, as in the tuition chart above.

This is a work by Dan Flavin, an artist I like. I was reminded of him recently as I happened to reconnect to a friend who introduced me to his work.

When I show images of Flavin’s work, people sometimes think I’m trying to make some kind of joke. I even had a long talk about his art — and its price — with a group of college students.

Here we have an instance of value being disconnected to the cost of production. If I used the same store bought supplies I could get a similar visual effect, but it wouldn’t carry the same value (at least to a collector — you could certainly personally enjoy the way it looks). In this case the value comes from the agreed recognition of a specific creator and his body of work. Value doesn’t come from adding up the cost of materials and adding overhead.

Value is sometimes disconnected from cost. While I put this example in the art category, this is most applicable to readymades (reconfigurations of existing products).

Spices

The value of spices changed in Europe as they went from rare luxury goods to common household items.

First, Europeans traded for spices and shipped them back to their home markets at great cost, for resale.

Some highly-prized spices were grown only in one location, had to be shipped great distances over land or by sea, and while high in desirability were also high in price. One source estimates 1.32 days labor to buy 100g of mace (part of the nutmeg seed) in the mid-1400s. Nutmeg itself was grown only on the Banda Islands (now part of Indonesia).

The first Europeans to arrive at Banda were the Portuguese in 1512. Various European countries traded with Banda for the next hundred years. But later the high price of spices produced a different strategy, where Europeans colonized the locations of spice production and increased the cultivation of spice plants.

For example, in 1621, Dutch colonists conquered and nearly wiped out the local Bandanese people in order to gain a monopoly on nutmeg and mace. Another couple hundred years later the British temporarily gained control of Banda and transplanted nutmeg trees to their empire, eliminating the monopoly the location had on nutmeg production. Today, Guatemala produces more nutmeg than Indonesia, with India close behind.

The elimination of a monopoly, greater production, and lower transportation costs drove changes in value for spices like nutmeg and mace.

Chicken feet (paws)

Systems of preference vary by location.

And as I’ve written in other articles related to production and animals, the answer to value questions is built into the animals themselves. (See The Cobra Effect and Vultures and Ventures.)

You can increase the size of chickens, you can bring them to market faster and breed them for faster maturity, but you can’t breed them for more than two feet (also called chicken paws) per bird. The chicken feet trade came at the same time as quick and inexpensive international transportation. The cost of shipping them from the US to other locations is low. That was not at all the case in the historical spice trade.

Chicken feet have very little value in the US but do have value as an export to China and Korea. The US started exporting chicken feet in large quantities around 30 years ago and today are one of the more profitable chicken parts.

The setup:

- Only chickens can produce chicken feet,

- Only two feet per chicken,

- Per serving, in some markets, people prefer to eat more chicken feet than other similarly restricted cuts of chicken,

- Shipping costs are low.

This leaves only one option: source chicken feet from a location that doesn’t value them. The consequence is a benefit of trade where one side can sell a formerly valueless product and the other side gains more of a demanded item.

Conformity and anti-conformity

A paper by Jonathan Touboul titled “The Hipster Effect: When Anticonformists All Look the Same” investigates value and identity. How do people demonstrate that they are not part of the mainstream? One way is to change our physical style — clothing and hairstyles being the easiest. Once there is a mainstream style it takes people who oppose the mainstream some time to recognize that the style exists. Once they do they start to act in opposition.

This opposition produces an oscillation of value.

Consider

- Forces combine to change value in unexpected ways.

- Timing and luck influence the value you happen to experience.

- Changes in value can be negative. For example, some cargo ships are avoiding the Suez and Panama Canals and sailing the long way to their destinations. The reason: the drop in oil prices makes the longer trip cheaper than using the canals.