Even if we’re not good at dealing with them, we tend to see a lot of systems surprises that arise from expansionism – the situations where something grows faster than expected, dangerous positive feedback loops, or good intentions with bad outcomes that negate the original good intentions.

So I was surprised when I recently learned about the way some forager hunter societies found to create stability in environments with both limited food (meaning successful hunters could accumulate status) but with few ways to store that food (limiting the ways others could accumulate status).

My main source here is a paper titled “Leveling the Hunter,” by Polly Wiessner.

In some foraging societies, successful hunters are “leveled” by limiting the amount of status they gain from successful hunts. As subsistence foragers in environments where meat cannot easily be stored, it’s better to share meat throughout the group as it is hunted.

Additionally, while skill plays a part in successful hunts, there is also the matter of luck. Distributing meat around the community according to a set of rules reduces prioritizing the successful hunter, limits bad feelings, and maintains an egalitarian community.

The system is often referred to as hxaro, a term used by the !Kung San (a group of forager hunters in and around the Kalahari Desert). Hxaro rules vary group to group, but often shifts the reward of meat from the successful hunter to the maker of the arrow that successfully hit the prey. Hunters regularly borrow arrows from others as part of their participation in this status system. Similar systems, with different rules, are found in many forager groups around the world, as Wiessner’s paper describes.

Why the interest in egalitarianism in the first place? Interestingly, since it is difficult to accumulate enduring wealth, forager societies don’t benefit from having strong leaders, as distinguished by hunting. Forager societies would rather pool risks and rewards in the form of meat and status distribution.

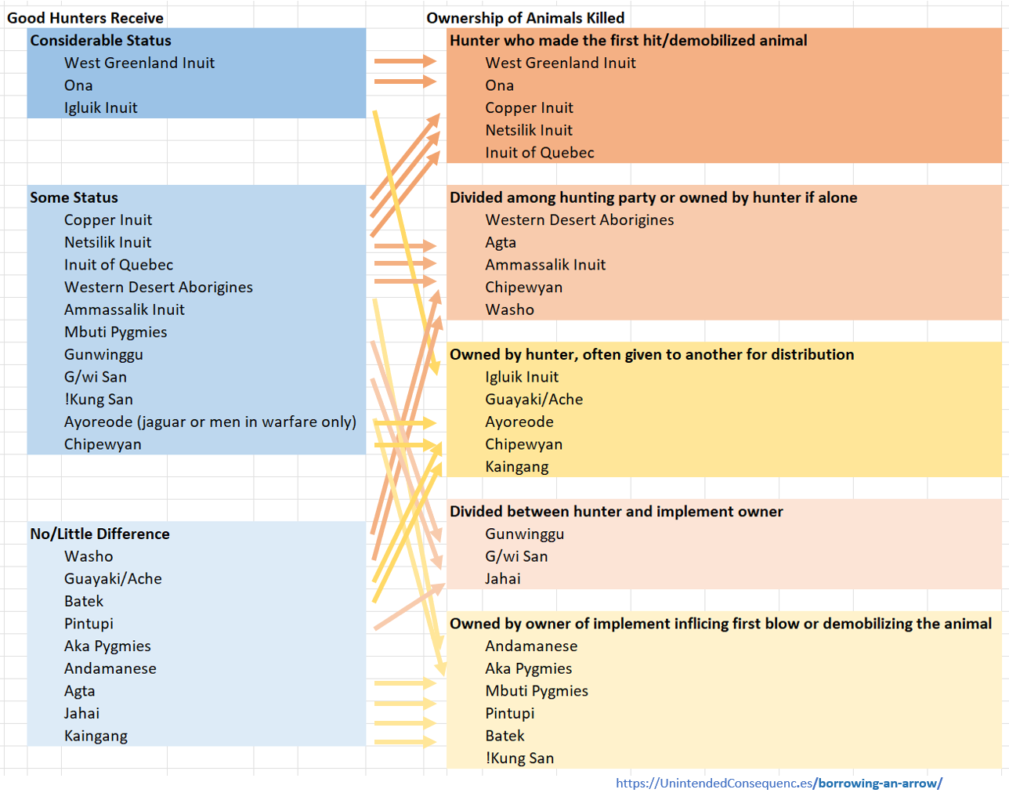

When learning about these systems, I reviewed a few tables of related social behaviors. This chart is a combination of several of Wiessner’s tables and where I’m looking for global trends. The redistribution system roughly follows the status system.

Status and Risk Examples

In which situations do we borrow an arrow, or intentionally move status from those who created the good outcome and in which situations do we keep status with the creator of that good outcome? Non-forager societies seem to take different approaches.

The following highlights other types of status and risk shifting.

- The individual is required to shift status and benefits to another party. Example: Hxaro, as practiced by foragers.

- The individual chooses to remove themself. Example: anonymous financial gifts to non-profits.

- The hierarchy takes the risks and benefits. Example: Elites historically were the ones to declare war and to fight in those wars.

- The hierarchy takes the benefits, but not the risks. Example: Elites declare war, but enforce conscription to shift risk to the mass population.

- The group works for its own benefit. Example: Corporate co-operatives share profits among employees.

I’ve written quite a bit here about ideologies and their effects, but mostly from larger-scale political and cultural examples.

Two of those pathways, on creating new sources of status as a social safety valve and on swaying public opinion using the “current thing,” present different extremes. The first creates new types of status so that there is enough for all and the second enforces certain directions of status based on what benefits a specific individual or group.

The hxaro system does something in between.

Also as the most successful forager hunters cannot go elsewhere where they’d be more rewarded, they have little choice but to accept the social rules.

Some social stories help maintain the egalitarianism of foragers. For example, some forager societies had the belief that from birth, each hunter had a preset number of animals he would kill. Others thought of killed animals as offering themselves up to the hunter.

We see similarities in non-forager societies. Blaming the economy. The muse that lives in the wall. Channeling God. Asking the universe for help. Predestination.

Here are a few other examples:

- The use of business goals and their effect on decision-making. For example, the exploding Ford Pinto cost/benefits analysis memo, where company employees explained why it was cheaper to pay settlements for dead customers than it was to redesign the car.

- The appeal to reason and the destructive effects that can follow. For example, creating a rationalist religion to replace Catholicism during the French Revolution.

- The trust in theory and the need to fabricate data to meet the theory’s demands. For example, the way high crop yield targets set by a bureaucrat resulted in gaming actual crop yields.

Looking at these examples across different time periods and places, there is something more in common. It was difficult for their participants to go elsewhere. As they could not easily escape, they lacked an option to avoid the social practice.

But Do We Know the Arrow-Maker?

As serious as the hunter foragers took their status shifting system, it was funny for me that the maker of an arrow was not always accurately known, as shown by this quote (emphasis mine):

“In an attempt to become familiar with the community as a whole, I began with straightforward interviews with each man about his arrows, photographed and measured them and purchased two which later would be used to find out who could identify their maker. Cumbersome as these interviews were after double interpretation, the San thought that this kind of work was hilarious and were eager to demonstrate everything in detail. After six weeks, I had talked with every family and had substantial data on /ai/ai arrows. One day while making summary calculations, a hunter came by and asked what I had found out. I had to admit that it was exactly what he and many others had told me in the first place — that each man makes the length-width ratio and ‘ears’ of each arrowhead slightly differently so that he and his close friends can recognize their maker. He makes them that way for no other reason than that is how he feels like making them that day. One year later when I quizzed several hunters on who had made what arrows, most people could not even recognize their own which they had previously sold me.”

– Pauline Wiessner – Hxaro: A Regional System of Reciprocity for Reducing Risk Among the !Kung San (Volumes I and II)

For hxaro to work as described, surely there must be no question about who makes the arrows?

Or maybe not? If hxaro serves to shift status and therefore maintain an egalitarian society, it doesn’t matter whose arrows they are believed to be as long as they are not the hunter’s.