The spark for this post was an article published in The Century Magazine in 1892. In it the author explains to a foreign visitor the odd way that Americans keep the peace. I couldn’t improve upon the article’s title, “The Great American Safety Valve,” so I stole it for my title.

It’s a short, informal article from 130 years ago, but there’s a lot going on. In it the author explains to a bewildered foreign friend how the US balances a large population that has been taught that the class they were born into doesn’t prevent them from rising to the peak of power, with the obvious lack of political offices. In 1892 language, “it is the birthright of every American boy to have the chance to be president…”

It might seem odd to turn to an obscure article from over a century ago, but the topic relates to today. Here are some of the main points:

- Countries are different in the available opportunities and choose different tactics to keep their populations peaceful.

- The story you tell the child will eventually be expected by the adult.

- Do not dismiss the importance of expectations and opportunities to fulfil ambition when it comes to national morale.

How do other countries keep their populations peaceful? There are different approaches. According to the article, centuries of history have their effect. In Europe the “undistinguished classes on the Continent submit contentedly to obscure conditions of life. It is the lot to which they are born.”

But contentment with one’s lot, if it can be maintained, may lead to social peace but also produces stagnation — economic and social. And how does a country produce that contentment to “obscure conditions,” anyway? Centuries of enforcement and persuasion from aristocratic society? If that doesn’t already exist, it can’t be replicated easily, especially not in a younger country.

For a country lacking that history, and with options, what would be desirable? It’s closer to what happened in the US.

In the US, people were told something different (remember this was from 1892). “But here every school-boy is taught that the highest stations are open to him; and in a thousand papers, books, lectures, speeches, and sermons he is told that perseverance alone will put the highest prizes within his grasp.”

But elsewhere, what happens when those centuries of submission come to an end? It depends on where and when. Here are a few examples we’ve seen around the world (with overlap between them):

- The emergence of communities abroad that started by searching for economic advantage. Large ones include communities with origins in China, India, Italy, Mexico, and more. These communities are bounded by the number of places having better economic prospects, whether through official or unofficial immigration or temporary work programs.

- The emergence of communities abroad started by people escaping political problems. Large ones include communities with origins in Iran, Burma, Syria, Afghanistan, and Vietnam. These communities are bounded by the number of places they can reach that have better political situations, whether through direct immigration, or temporary refugee camps.

- The intentional creation of economic and managerial opportunities for the discontented, outside of their home countries. Examples include the age of exploration and colonial post opportunities created by the Spanish and British empires. The goal of participants was often to return to their home country, assuming they had become rich and didn’t “go native.”

- The intentional creation of managerial opportunities for the discontented, but within the home country. Here the best long-standing example is the Chinese civil service exam, with other countries having something similar. Positions of this type are highly competitive and can typically only absorb a small number of applicants.

- The intentional creation or emergence of economic opportunities arising from open systems, community membership, and the encouragement of hard work.

The article’s author tells his foreign friend of the importance of American “social, business, religious, and other associations, all of them elaborately officered.” He further observes: “Take a city directory…. you will see ample provision for the local ambitions of all the inhabitants… I made a test case of one small town, and found that every man, woman, and child (above ten years of age) in the place held an office — with the exception of a few scores of flabby, jellyfish characters, whose lack of ambition or enterprise removes them from consideration as elements of the problem.”

I haven’t noticed anything like that flurry of membership in associations today.

Why? Do we just have more jellyfish characters these days?

March of the Volunteers

Temperance movements, abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, and others from the time of the article, were all products of self organization.

We might call it volunteering, in a general way.

Half of capable seniors currently volunteer. But with more aging baby boomers, that might mean that there will be a dramatic drop-off as the same demographic ages out of volunteer capability. Will the younger generations choose to participate similarly?

Also related is another type of leadership. Where the earlier article referenced association leadership as a way to keep a population content, other forms of displayed leadership also emerged. Ones where display of leadership was the goal, rather than the goal of filling peoples’ ambition or creating actual needed institutions.

The more recent (and cynical) version is “show leadership.” For example, that in which university applicants create short-lived new clubs for the purposes of boosting the example of their own leadership. That in turn boosts their likelihood of acceptance to university. A means to an end.

But unlike the system described in The Current Thing, where information cascades that people down a specific path, the article’s safety valve outcome is stable — as long as there is growth in population and needs. The civic associations and volunteer organizations grow organically, they enable socialization among participants, and build connections across communities.

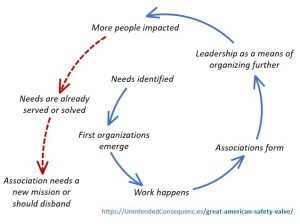

From no associations to a full (not perfect) market, the cycle looks like this:

[chart]

[chart]

But when population growth slows, needs are satisfied, or old associations clog up the ability to create new ones, there’s a new problem. Too many associations. Do they remain or do they disband?

Do bottom-up associations and volunteers remain as the go-to means to build for the future and provide destinations for the ambitious, or does the system go more top-down? That is, does the government take on the role the associations formerly held?

As Reagan said, many Americans believed (and probably still believe) that “The top nine most terrifying words in the English Language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” The history of self-organization and the output of that safety valve is why the historical American distrust of government can be a feature and not a bug, at least sometimes.

The article’s one assumption that seems out of place, today at least, is that political office would even be something to aspire to. While it might be within reason to expect political office, why not take one of the other options? Why not be content without political office as long as you are successful in other realms?

New Observations

How much of a 130-year-old article is still valid today?

The US of the late 1800s was in a period of great growth, producing one of the world’s highest economic output per person. That being said, just a year after the 1892 article, the US went into a recession.

An enduring thought is that the path to ruin is for a population to be pessimistic about their future. That they should be content with what they have. Or that anyone successful today benefitted at the expense of others. Or that there are boundaries to what they should ask. Or that they do not get to determine what they should build because the building is already complete.

That audacious quote — “it is the birthright of every American boy to have the chance to be president” — is exactly what you would want to tell people in the US of the late 1800s. In a big country with a population small for its size, with many gaps in needed infrastructure — both physical and social — why wouldn’t you want your population to think big?

Looking at changing perspectives it’s hard not to wonder if pessimism is just a swing on a pendulum or whether there was a push.