People seek asylum for different reasons. Sometimes, a country becomes unsafe because of one’s identity — as a member of a targeted ethnic, religious, or political group. And sometimes one’s actions — sometimes even unintentional — make their home country unsafe.

The idea of seeking safety elsewhere in the world is an interesting one because, even with the recent refugee crises, it has historically been relatively uncommon. (Asylum is the protection a nation grants to someone from another country, often as a political refugee. An asylee to the US requests asylum while in the US but a refugee requests that protection while still outside the US.)

But today — and maybe because I’m both a friend of the individual and a writer — I’m focused on an instance of someone seeking asylum because of something that they wrote.

For my friend Chris (not his real name), a native of Russia, though not ethnically Russian, the unintended path to asylum in the US started with a post on Facebook. Here’s the English translation of his post which spiraled out of control. (I quote much more than usual in this article, but feel that it was needed to present the severity of what happened in his asylum case.)

Chris’ translated Facebook post:

“I want to repent for my country. For all the horrors of pre-revolutionary (Tzarist) Russia, of the Soviet regime, of Russia of the 90’s, 00’s and 10’s. For the genocide of Chechens, Armenians, Poles, Ukrainians, Baltic peoples, (Crimean) Tartars, other Caucasus and Asian peoples, and, most importantly, of Russians themselves. For slavery (serfdom) and the Prison of Nations. For fascist regimes of all (Soviet and ex-Soviet) dictators of this savage, medieval, world. For persecution of the Jews. For weak leaders of the country who could not resist their base instincts and needs. For stifling of will and liberty of all people of the past and present. For building a ‘wall’ against whole civilized world. For Crimea, Donbas (war in eastern Ukraine), and the downed (civilian) Boeing. For rigged elections. For lies and thievery of our leaders. For naivete of all others. For nuclear weapons, AK-47 assault rifles, and other killing machinery (i.e. proliferation of cheap advanced Russian-made weapons all over the Third World, in the hands of savage dictators, terrorists, and child soldiers). For invasions into others’ lands. For violating human rights. For poisoned and killed people. Please forgive me!”

There’s a lot in there. And unfortunately at the time for Chris, it was published the next day in a Russian newspaper.

Of the responses, there are many so vicious that I can’t bring myself to reprint them. But here are a few, also translated to English with notes and quoted in Chris’ asylum application.

“The boy is confused, like Leon Trotsky in his day, let him share his fate (killed by a Russian assassin while in exile in Mexico). But seriously, how his relatives will look into people’s eyes now, especially parents who have raised a traitor! If I knew them in person, I would spit in their face without regret!”

“Traitor of Motherland, he repents! Our long-suffering people know everything but will not bend knees to any foreigners. Execute this liberal scum, he must pay moral damages, he imagines himself to be Jesus Christ…. If f**er’s repentance for his country is thoughtful and sincere, maybe he intends to sacrifice himself for us all, like Jesus?”

From a government official:

“Just kill yourself by hitting a wall with your head. This would be your real repentance.”

From a well-known entrepreneur:

“More likely, you’ll have to apologize to Kadyrov.”

This is an allusion to Ramzan Kadyrov, Chechnya’s ex-terrorist dictator, who is claimed to have assassinated liberal politician Boris Nemtsov.

Chris did have a few defenders though. One anonymous person wrote:

“After the collapse of the Soviet Union the whole world waited for Russians to repent, but they didn’t, so we got NATO expansion in Eastern Europe. Now finally there is at least one man, a patriot of his country, though not Russian, but a real patriot of Russia, who took upon himself the responsibility to repent! Such brave people who are ready to sacrifice themselves, to be burned at a stake like Giordano Bruno or Jeanne D’Arc, are truly rare. I thought there are no more left – but it appears that there are!”

A few other quotes from Chris in his application:

“One would not think that a mention of any of the well known historical facts could cause an uproar in a country which, while not democratic in a strict sense and ruled by a de facto dictator, still effectively has freedom of speech (at least in the internet-based media – the printed ones and TV channels are all government controlled and / or censored). That is, neither officially nor legally, free speech is not directly punishable (nor even deplored in official information channels by Putin’s propaganda ‘artists’). Yet the reaction of the ‘public’ (at least the vocal part thereof) that I received proves otherwise and exposes the true, deeply Fascist nature of the regime that has penetrated the very souls of the people who live (and even suffer) under it, at least to the extent the Nazi regime had penetrated German souls! Ordinary people (not professional ‘punishers’ or secret police) were ready to mob and lynch me, tear me apart like a pack of wolves (virtually or even literally), in retaliation to my criticism of the ‘pack’. Such pack-like behavior of the vast majority of the ‘public’ (all but exceedingly few comments were either extremely or viciously negative or outright threatening) is characteristic only of advanced and outwardly aggressive Fascist regimes (far beyond Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’s Spain, Pinochet’s Chile, or Galtieri’s Argentina, which Putin’s Russia is usually compared to), like WWII Germany or Japan. Russian ‘Street’ is MUCH worse than the countries ‘outside’ behavior would seem to indicate.”

We see milder versions of what Chris experienced all around us. Just go on social media. But what creates the environment for people to get in such trouble for a critique — even with good intentions — that they should seek asylum? That brings us to the concept of the scapegoat. And how it’s changed.

Scapegoating, exile, and asylum

There are several historical types and purposes for the scapegoat, including to expel someone unpopular to keep the peace, or to cast someone out having already assigned them the sins of the group.

Since Chris’ personal experience took place online (even the print newspaper article about him was relayed back to him online) I thought it a bit different from what used to happen in history.

Here’s are some historical or religious examples of scapegoats.

In Tibet:

“On the appointed day with a bloody sheepskin bound round his head, yak’s entrails hung round his neck, but otherwise naked, he takes his position in the local Jong, or Fort…The people fling after him stones and dirt, taking, however, great care not to wound him severely, or prevent him from reaching the open country. Should the scapegoat not succeed in making good his escape, the devils would remain in the place.”

In ancient Athens, in certain years, there would be a vote over who to ostracize — to banish from Athens for a decade. Voters wrote their preferred victim’s name on pottery shards.

The other related ancient Greek practice was that of the pharmakós (where the word pharmacy derives) which is the practice of “sacrificing” (usually figuratively) or exiling a human scapegoat for the benefit of the community. The pharmakos:

“cleanse the cities by their death. For the Athenians would nourish some who were exceedingly low-born, penniless, and useless, and when a time of a disaster of some sort came upon the city… they would sacrifice these to cleanse the city from the pollution and from their evil….”

“It was the custom at Athens to lead in procession two pharmakoi with a view to purification. And this purification was… to avert diseases….” (translation from Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion).

Meanwhile, in ancient Sicily, a slightly different practice of “Petalism,” as described in the history Diodorus of Sicily. This seems closer to what Chris experienced.

“Now among the Athenians each citizen was required to write on a potsherd (ostracon) the name of the man… most able through his influence to tyrannize over his fellow citizens; but among the Syracusans the name of the most influential citizen had to be written on an olive leaf, and… the man who received the largest number of leaves had to go into exile for five years. For by this means they thought that they would humble the arrogance of the most powerful men in these two cities…. Among the Syracusans it was soon repealed for the following reasons. Since the most influential men were being sent into exile, the most respectable citizens… were taking no part in public affairs, but consistently remained in private life because of their fear of the law…. whereas it was the basest citizens and such as excelled in effrontery who were giving their attention to public affairs and inciting the masses to disorder and revolution…. A multitude of demagogues and sycophants was arising, the youth were cultivating cleverness in oratory…. As a result the Syracusans changed their minds and repealed the law of petalism….”

But the most famous version of the scapegoat is probably from the book of Leviticus in the Old Testament. From Leviticus 16 (numbers being the verses):

“(8) He is to cast lots for the two goats—one lot for the Lord and the other for the scapegoat. (9) Aaron shall bring the goat whose lot falls to the Lord and sacrifice it for a sin offering. (10) But the goat chosen by lot as the scapegoat shall be presented alive before the Lord to be used for making atonement by sending it into the wilderness as a scapegoat.”

Scapegoat becomes asylee

Asylum is an inversion of exile. Someone forced out — either actually forced out or caused to leave because of danger — is then welcomed in somewhere else.

When groups of people have problems, it makes sense that some want to find a scapegoat. But why should another group welcome that scapegoat and turn them into an asylee?

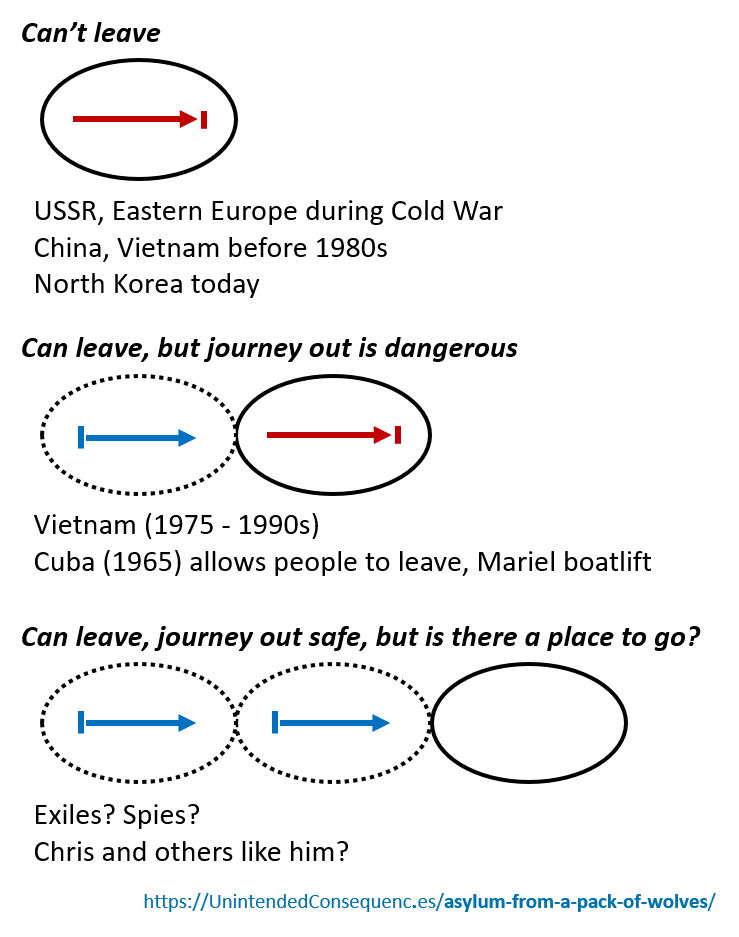

Granting asylum (or refuge) is politically easier when the grantee comes from a place deemed to be an “enemy land.” For the US this includes dissidents from the Soviet Union during the Cold War, 1970s Vietnam “boat people” after the US retreated from the war, or students fleeing China after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. It’s also easier when the asylum seeker is a senior or recognized person who may bring something of value, as in the case of spies or government officials fleeing North Korea. It’s more complicated when asylum seekers are from places where there is less of a feeling of competition or benefit and also more difficult when their numbers are large, as today with refugees in Europe or people fleeing cartel and government violence in Latin America.

But Chris’ situation struck me as different — and, well, modern. His case wasn’t like that of past Russian asylees Mikhail Baryshnikov or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, internationally famous for their art, who gained asylum at the height of the Cold War. He wasn’t part of a group that the US felt they owed (and granted refuge to), like those fleeing Vietnam or Cuba.

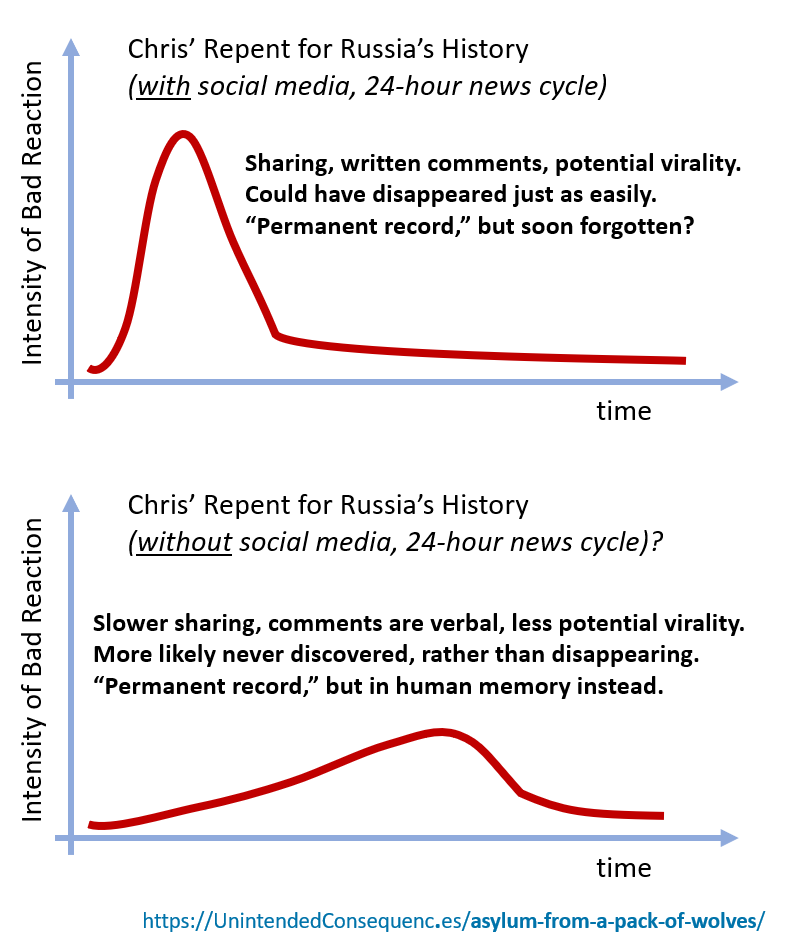

Chris’ situation was exacerbated by social media and the 24-hour news cycle. Unlike the scheduled ostracisms, pharmakos, and scapegoating historical examples, today the same effect can happen at anytime. Actually, the speed with which things happen today helps create the environment in which asylum must be granted.

Here’s how Chris’ situation played out with those new factors of communication and how it might have played out without them.

If Chris had not made that post online there would have been fewer options for it to be quickly amplified. Being online gave no guarantees of what might happen, but opens the possibility that it would burst up dangerously or fizzle out and be seen by no one. He was one of the few people able to benefit (and first suffer) as though he was more famous. His message was amplified by extreme emotions and an algorithm that probably amplified views of his post.

Did new communications technology and social media algorithms impact his situation? I think that’s clear.

Consider

- One nation’s loss can be another’s gain.

- The loss and gain can be managed more easily with smaller numbers of people. When there are refugees numbering in the millions, this is a statistical decision rather than a personal one.

- Communication technology and sharing can exacerbate specific cases.