Those of you who work in a large organization occasionally might find yourself shaking your head thinking about a colleague: “What do they do all day?” Some of you might even think that about yourselves. Or you might think that about people in another department, especially those with whom you have an adversarial relationship.

At the same time, you also might be uncomfortable with the automation of certain tasks and possibly seeing those jobs disappear. Even those jobs of the unproductive humans you shook your head at. Fear of job automation and its unintended consequences has people thinking, but what are the roots of this thought?

Isn’t the history of technology about removing humans from a task and replacing them with machines, even simple ones?

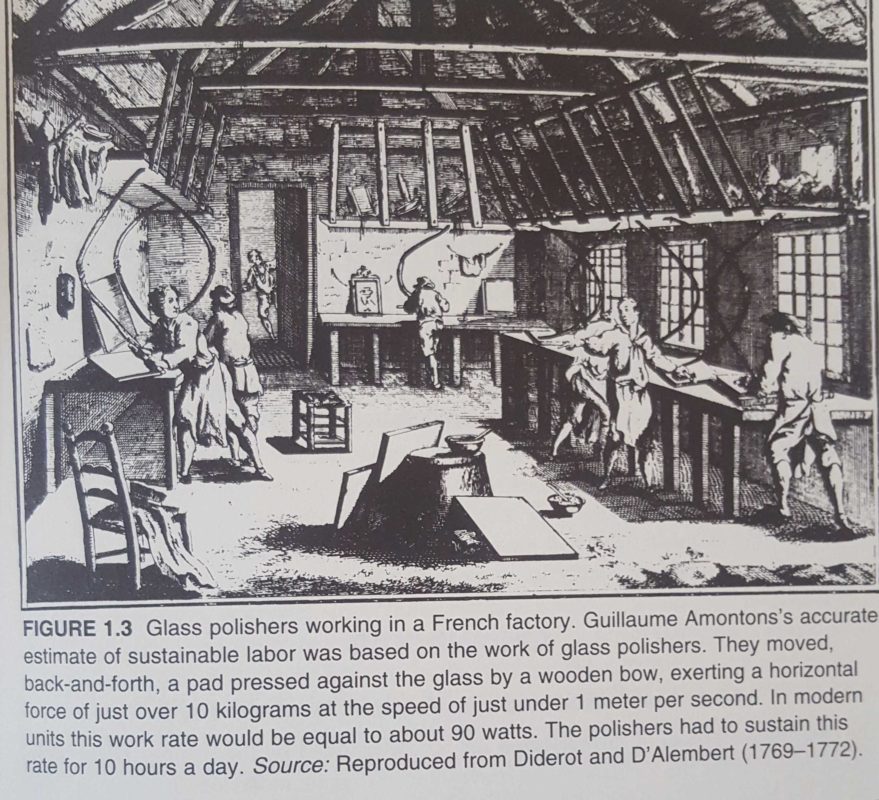

Here’s an example from Vaclav Smil’s book Energy in World History.

Do you really want to be a glass polisher? And do the unintended consequences of job automation include creating shoplifters?

People build products and companies to automate tasks, especially costly, dangerous, and monotonous tasks. For many of the tasks already automated, the effect is already invisible, the history forgotten, unstudied, and unknown. People find it surprising to learn that anyone used to do these specific tasks manually.

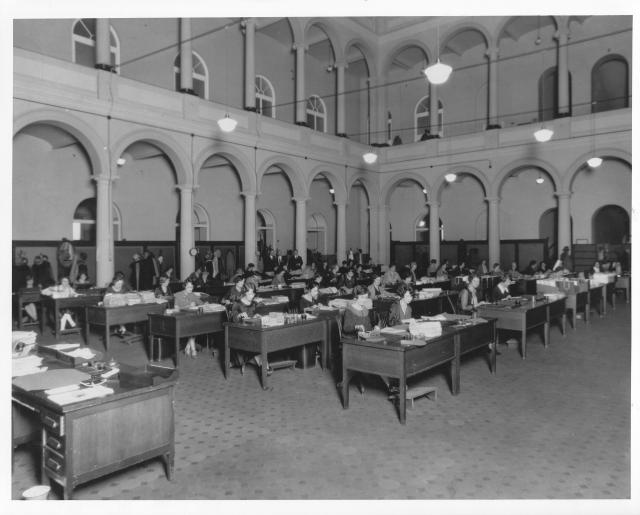

As others have said, everyone in the picture below is now a cell in a spreadsheet.

Seen this way, technology is always subtracting humans, or at least moving them from one legacy task to another new one.

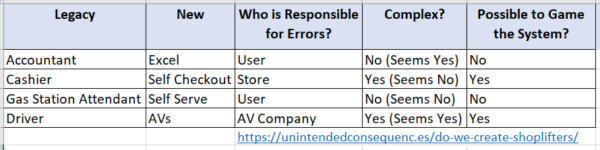

Technology also shifts responsibility. In the accounting example, now that I use Microsoft Excel to do my calculations, who is responsible for errors? Me, the user. Not Microsoft. Also not the calculator-punching accountant who I might have hired earlier.

But this isn’t true across the board. Responsibility falls differently with different implementations, I believe in this way.

- Accountant -> Excel. Subtraction of humans results in more complex financial models, with more rapid iterations (accountants still exist of course, but focus on other issues). Not possible to game the system since users own their errors (not counting misuse of accounting rules).

- Cashier -> Self Checkout. Subtraction of humans gains some cost saving (possibly) for the stores but in many cases lowers customer service quality. Possible to game the system — bad feelings and ease of theft create shoplifters.

- Gas Station Attendant -> Self Serve. Subtraction of humans happened after cars and gas stations became safer, standardized, and people grew used to lower service expectations. Not possible to game the system (except by theft before prepayment was standard).

- Drivers -> Autonomous Vehicles. Subtraction of humans claims to result in fewer accidents. Possible to game the system by behavior change, treating AVs differently than human-driven cars, hacking, and more.

The above subtractions led (or will lead) to previously employed humans needing to find jobs doing other things. In some cases, these subtractions also led to unskilled people with fewer options for employment, or young people lacking low-skill work to gain a path into skilled work. Changes can lead to emergent behavior that explains some of the way we react to these new technologies.

Let’s look at other examples from our list.

The Modern Argument

The modern argument for automation plays to modern concerns, often efficiency (the accounting example), meaningful work (cashiers and gas station attendants), and safety (AVs).

The checkout cashier is a relatively new job. Only with scale did stores reach the size that they needed people in that role. Formerly, the job of taking payment for goods was performed by the store owner (in small shops) or by a set of clerks who also helped people find merchandise, measure it out, pack it up, and more. In some cases, the cashier role historically took some level of mental math. (The cash register actually was invented as much to solve the problem of employee theft as anything else.)

With efficiency at scale, the cashier role became unskilled. Pass bar-coded items past a scanner and collect the total. The work became more efficient. More customers served per cashier, fewer mistakes (possibly), and integrated outbound purchases with orders into the inventory system.

So in theory it makes sense to automate the cashier role with an automated checkout. And yet, the automated self checkout — a process much simpler than building an autonomous vehicle — still causes many errors and is often little enjoyed by customers.

Stores in theory deploy self checkouts for efficiency but in practice it is different. Since the self checkouts don’t work perfectly (whatever that means) people are often frustrated with them or take advantage of them. Some stores employ a clerk to focus on customer problems with self checkouts themselves.

The self checkout solves the question “What does a cashier do?” with the answer: “Handle customer transactions.” When really, the question has a broader array of answers, including “generate positive feelings, answer questions, take up slack elsewhere in the store,” and more.

In theory, someone would think… being a checkout clerk is not a job humans should do, right? Shouldn’t we want to replace that job with self checkout?

This is an interesting case of automation in that it’s not so much automation as it is shifting who does the work. Rather than hire cashiers to handle customer purchases, the store instead makes each customer their own cashier. This is also called “shadow work.”

But in self checkouts, there is a twist. This implementation of shadow work results in more shoplifting.

As reported, this is what can happen.

“A 2015 study of self-checkouts with handheld scanners, conducted by criminologists at the University of Leicester, also found evidence of widespread theft. After auditing 1 million self-checkout transactions over the course of a year, totaling $21 million in sales, they found that nearly $850,000 worth of goods left the store without being scanned and paid for. The Leicester researchers concluded that the ease of theft is likely inspiring people who might not otherwise steal to do so…. As one retail employee told the researchers, ‘People who traditionally don’t intend to steal [might realize that] … when I buy 20, I can get five for free.’ The authors further proposed that retailers bore some blame for the problem. In their zeal to cut labor costs, the study said, supermarkets could be seen as having created ‘a crime-generating environment'”

That reminded me of what Charlie Munger said in his talk on “The Psychology of Human Misjudgment”: “[P]eople who have loose accounting standards are just inviting perfectly horrible behavior in other people. And it’s a sin, it’s an absolute sin. If you carry bushel baskets full of money through the ghetto, and made it easy to steal, that would be a considerable human sin, because you’d be causing a lot of bad behavior, and the bad behavior would spread.”

Self checkouts create shoplifters.

Calling Shotgun

“What is driving?” The best answer I’ve seen is the frustrating answer: “Driving is all the things you do when you drive.” But the great thing about that answer is that what seems like a straightforward question is shown to be complex. Driving is both about guiding a vehicle from point A to B and also about all the unexpected occurrences that will pop up along the way. That’s why apart from the autonomous tech, the path to widespread AVs will be harder than expected due to systemic risks posed by hacking and bugs.

Like the reasons outlined above, the arguments for AVs come in a few main varieties. There’s the argument for efficiency. Resources can be used better – avoid traffic jams with intelligent routing, avoid the waste of car ownership when these machines can be shared, optimize or avoid the need for parking, reduce or eliminate traffic accidents and deaths. But if you’ve been reading this blog a while you know that these arguments are best expressed in theory because they don’t necessarily work in practice.

AVs can result in more car time consumed (cheaper and more available), more traffic (why take public transport), an uncertain reaction to costs of parking (circle the block rather than pay), more chaos in accident rates (lower accident baseline but spikes that propagate at scale due to hacks and bugs). The system that emerges is likely to be different from what “should” exist in theory.

Like the Charlie Munger quote above, will AVs push people into unethical behavior? What other effects will we see from automation of other jobs? Besides shoplifters, what other behavior will we create?

Consider

- New tech (even what looks primitive today) has always enabled people to automate jobs.

- There are benefits and costs to job automation. We may prefer automation when there are benefits of cost, safety, and other efficiencies. Those benefits come with costs.

- Think about how responsibility, ability to game the system, and complexity influence outcomes.

- There is value in having low-skilled work. People need options for this work, even on a temporary basis. It can also be a path to higher-skilled work.

- Subtracting humans can push people into unethical behavior.

- There is chaos when these changes happen too rapidly for unemployed humans to find new work. Think through the changes and choose which types of chaos are worth preventing. Even then it might not be possible.